Pre-Qin period (21st century BC-221 BC): simple and loose, simple and generous

Characteristics of dress:

Upper garment and lower garment system: the upper body wore a garment (衣 yi) and the lower body wore a skirt (裳 shang), and the garment was divided into two systems, with the overall looseness of the garment, making it easy to work.

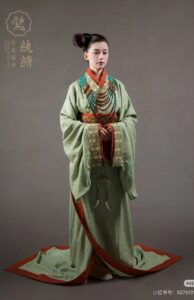

The upper garment and the lower skirt(上衣下裳)

Straight Train and Curve Train: Noble women wore deep clothes with a curved train, the hemline of which was bent and folded, making them look dignified and elegant.

Modern Straight Train Recovery

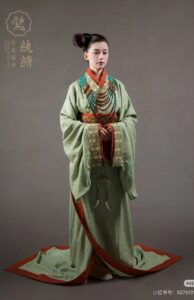

Modern Curve Train Recovery

Colour: The nobles wore dark-coloured clothes, while the commoners wore plain clothes such as linen.

Wedding Clothes of the Eastern Zhou Period

Hair style characteristics:

Popularity of buns: Women often wore buns, such as the ‘yabun,’ ‘chignon’ (for unmarried girls) and ‘chignon’ (for married women).

Simple decorations: Noble women used hairpins and hairbands to decorate their hair, but the overall style was not complicated.

Left: Partial chignon Right: Dropped chignon

Makeup:

Pre-Qin women’s makeup natural and dignified, the aristocrats commonly used powder whitening, oblique red cheeks to increase the colour, moth eyebrows long and thin, vermilion dyed lips, forehead ornaments embellishments, high buns and jade ornaments, the overall elegance and generosity.

Recovery Makeup

Shoes:

Women’s shoes in the Pre-Qin period mainly included lü (履) and ju (屦). Nobles wore silk embroidered shoes with thick soles and jade ornaments, while commoners mostly wore straw or hemp shoes, which were simple and practical.

Restored brocade-covered lacquer shoes from the Mashan Chu Tomb.

Conclusion:

The history of women’s dress in the pre-Qin period is a history of the early practice of the ritual system in disciplining the body through material culture:

The double yoke of class and gender: Silk dresses became a symbol of aristocratic status, but at the cost of common women’s textile labour;

The germ of resistance: the mobility and diversity of dress in Chu during the Warring States period (e.g., the ‘lapel gown,’ a variation of the deep garment) suggests that ritual control was not yet absolute, setting the stage for a breakthrough in later times.

The dress system of this period not only laid the foundation for Han and Tang costumes, but also profoundly influenced the millennial narrative of Chinese women’s ‘body-identity’ relationship.