Exploring Effectivity

One of the foundational texts, one could say, in this program, pops up at the beginning of the curriculum. The New Urban Agenda, the mouthpiece of the ever-reliable UN, outlines requirements and makes demands on what makes a real 21st century city sustainable, and therefore equitable. Fair enough.

The handbook outlines its objectives, stating clearly that, given the interdisciplinarity of urban development at large, the recommendations, strategies and concepts covered would “require coordinating various sectors to achieve sustainability and success.” It continues that the NUA intends to leave no one behind, ensuring as ever sustainable urban economies – that are also inclusive – and doesn’t stop there. In fact, the NUA goes on to establish its legitimacy, citing the process and work done extensively that lead to the production of this handbook, actionable in any country-wide, regional, and local context.

If that is so, then this means the handbook can be applied – with some tweaks and modifications – to any geography, any sociopolitical context. The NUA says so. Then why are the systems of cultures not as close to the Eurocentric norm accepted (and propagated*) by the UN not treated with the same level of possibility and dignified language?

Why does it not bear mentioning that some of the different land management systems were a result of UN in position through IMF, remnants of colonial systems, and other vestiges the UN has not raised a finger to help relieve, despite the bodies’ apparent mission of promote equitable opportunities for growth throughout different nations?

Planning for typical urban renewal with strategies that have heretofore been applied to (and not even always worked for) a Western city standard, and now expecting these strategies to be simply transplanted on possibly different climates, and definitely different cultures, which would have shaped city – to some extent – differently, with spaces built for different purposes and functions.

Why does the language dismiss these practices and norms? Why does it not take the perceived difficulties as challenging contexts that the NUA should mold to? Instead, we get this address that seems to sweep these contexts to the side; no note of work on going to understand the intricacies and come up with localized solutions – the way the NUA boasts it can for other places – perhaps even all other places.

If the language in this post has seemed biased so far, or too demanding, let me go further. While the NUA was introduced in Evaluating Sustainable Lands and Cities, this next point comes from a case study presented in another course, Envisioning Sustainable Lands and Cities. One of the case studies covered was on REDD+, a UN program dedicated to positive climate efforts – in developing countries. That premise alone is two-toned; it seems understandable that a developing country would focus and prioritize improving more imminent facets of health, housing, economy and self-reliance issues through education, easily acquired energy, and so forth, as soon as possible. Trying to get there fast might overlook sustainable practice. Having a somewhat ‘global’ task force from the UN would help to keep such efforts aligned with sustainable practice, which, as we all know, has lasting impacts not only locally, but worldwide. But is this what REDD+ truly is?

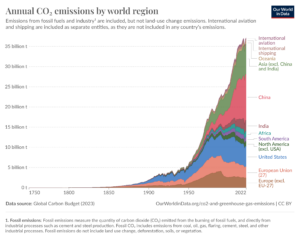

The scenario has more nuance to it. A hefty portion of these developing countries are recovering from something. They are recovering from exploitation of developed countries; one could look at a map and note down which country has however many emissions, which country is recovering these emissions… but the maps don’t come with backstories or exposition.

China’s rate of increase of annual emissions is as high as it is because, aside from the sheer population and population density, they create and export according to international demand. Conversely, we see tons of waste that the UK may boast of recovering energy from through recycling can easily be – and have been, as covered in the Ecocities course – lies for publicity/marketing. All of which to say, developing countries are ‘developing’ past the ailments that ‘developed’ countries scorched onto them. Developed countries – usually former colonial powers – did not pay respects to, or recognize, the ecologies of balance in the lands they ruled over; they simply exploited them, with ‘sustainability’ only occurring as a means of keeping conquered land both productive and docile enough to continue exploitation of.

What REDD+ and its investors set roots down in developing countries for, is an extension of that seemingly ingrained habit – where the developed countries are lacking, the developing countries may be taken advantage of, to fulfill their ‘part’ in this issue that developed countries began and spread and are at causative fault for in the first place.

Take Indonesia; formerly under Dutch rule, it forged its independence and paved its path to international respect as its own sovereign nation by inevitably following Dutch/European suit in multiple areas covering the constitution. It was, and still is, standard procedure. Unless one creates one’s own, independent, resilient ecosystem, one must exchange with others’ ecosystems; in order to do that successfully, these ecosystems must be compatible in some way. Other ecosystems aren’t wont to change – so one must change to survive. And so, Indonesia survives. Indonesia’s land laws and recognitions of deeds, however, are a source of struggle for many citizens; there is a difference between the regional/local indigenous deeds and acceptances, and the international standard regulatory recognition from the Indonesian government. Independent from the Dutch, causing property rights issues with civilians due to the Dutch influence in its laws. Surely, if the UN comes forward with a ground operations team geared towards ‘solutions’, one may expect the UN to try and do good by and for the local people – perhaps try and help locals overhaul the legislatures for sensitivity towards a more appropriate context: land rights for people who not only own the land having owned it for centuries, before the Dutch and before the advent of the unified Indonesian government, but know how to live peacefully in an ecology where the land has its own rights and needs. An ecology where they are well-versed in stewarding. This would certainly allow the local residents their own individual power, voice, and sway, as well as keep the natural resources in a careful balance that they have generational experience in cultivating and maintain. This is sustainable, inclusive, equitable practice.

What REDD+ is here for, however, is the ownership of Indonesian lands, the rule-setting of Indonesian lands, and the circumstance-shaping of Indonesian people (without truly listening to them), in order to “responsibly retain a carbon sink for the planet.” To my admittedly unseasoned and unprofessional ears, this sounds largely self-serving, short-sighted, and without earnest regard for the indigenous Indonesian people. Isn’t that what it is? REDD+ descends into this diorama playing out on a national scale, thousands – probably tens of thousands – of people locked in land rights struggles, strife, and the inequity that abounds because of this, and the UN decides to overlook its principles promising ‘no one left behind’ to fully leave entire people behind, so it can jump the gun on forest landownership, create maintenance rules regarding the forest, without listening to local dissenting opinion (worse, listening and dismissing).

Why would these Merabu villagers, already facing trouble with land property, the government, bearing the brunt of the economy and the shifting country, pick one more problem to raise and for – if that problem did not truly warrant such a reaction, if it did not immediately affect them? Despite implementing a ‘participatory process’ where villagers were kept in the loop of discussions, and their concerns and suggestions heard, the concerns of the village’s community and spiritual leader and those who agreed with him were not relayed forward to the decision-making circle. Why was the village leader not already in that decision making circle?

The arguments were of humanitarian importance, had the UN REDD+ team stopped to consider the implications of the leader’s complaints. The village had always been stewards of the forest – in that generational, ecologically formed tradition. The REDD+ team taking the forest land rights away from the villagers and instead relegating them only to an overseeing/managerial status so the village could continue to ‘steward’ in name, without power, on behalf of a very differently, not as intimately, and not as knowledgably informed UN (here the difference between having information, and being knowledgeable must be drawn). It’s not hard to guess how that plays out. The UN makes decisions inappropriate for the local context, going against its own statement that such decisions would require coordinating various sectors to achieve sustainability and success – since there is less coordination and more acts of will. The village is driven to drastic measures as a result. They were barely managing financially before the REDD+ team arrived. After the new UN-enforced rules were set, they began to do even worse, having to work within lower stratified levels of freedom as prescribed by ‘UN rule’ (a strange turn of phrase, almost nostalgically harking back to a time in history where the people of this land had to go against their own customs to satisfy what a foreign (white) party believed to be the ‘greater good’…) and resorted to shifting the land rights to an oil company, just so that they could obtain the bare minimum required to survive. The UN’s projected sustainability and success not really anywhere to be seen.

Had REDD+ been a team sent to consolidate laws/land recognitions into a single, cohesive system, the villagers would have been able to steward the forest as sustainably as they had done for centuries before the advent of Dutch empire, independence, or the UN. The carbon sink of the world located in Indonesia would be have remained more or less intact – maybe even grown, and adapted to shifts in the land. The villagers would not have shifted land and sold rights to oil for the sake of a shot at a future. Instead, we’ve got what we have now, because the UN is only really united for the cause and concerns of the developed, the privileged, the able-and-capable, the guilty of tossing national trash down other nations’ throats, the let’s not solve our problems, let’s just make them someone else’s team.

And that is something the UN is wont to do, it seems: address large issues short-term. Real problems get little band aids. Then then warrants some rendition of applause.

*Take the refugee crisis. The UNHCR drew up a Convention of the Status of Refugees in 1951. The context was the Cold War of 1948, and the refugees were Eastern Europeans fleeing the Iron Curtain. The Convention, complete with its definition of a refugee, and the clauses of agreements and practice set out to shelter said refugees, was as Belts & Collier put it, “unambiguously a product of its time and place.” It was wholly temporary, and only for the Europeans it was written for. The refugees of today and the refugees of the Cold War differ greatly – contexts of time, technology, geography, and race; different wars, different reasons to flee – different reasons that could lead to long-term or even permanent resettlement. These changes and differences have not been recognized; UN shelters remain inadequate in the long-term: quick fix camps. Despite there being seven decades between today and the drawing up of the Convention, more than enough time for close study, revision, and significant improvement of refugee response. The short-term solutions that the UN provides in situations that require long-term interdisciplinary, coordinated thought and action, result in a limbo that refugees stay in and lose their lives to for years. And this is for the refugees that get lucky. For the rest, fickle court rulings can indefensibly decide to deny shelter to refugees based on the Convention’s wording that had applied to a specific group of Europeans in the 20th century and now, in a familiar twist of Eurocentrism, must apply to everyone, everywhere, for all of time. Since the UN doesn’t seem to be interested in changing the status quo fundamentally any time soon.

Questions I have regarding this & somewhat related concerns

Things to look into later:

- The efficacy of polluter pays in the UN. How far does that go? Who has paid? How did it help?

- The previous concept was introduced in Understanding the Climate Crisis. The following concept – NAAPs and the like – were also introduced in the same course. I am interested in the hand UN plays once a NAAP has been admitted and approved – does the UN help lesser advantaged countries reach their goals in any way? Let’s say, Palestine’s NAAP and its 2020-2024 progress. With a significant amount of its land razed to the ground in a UN-recognized genocide (for whatever that recognition is worth. It does not seem to be leading to practical action) and UNRWA efforts bombed multiple times, no doubt taking out of action many officials who may have been in charge of machinating, evaluating and recording NAAP-related national progress, what does the UN consider being the next step in aiding Palestine towards these goals? Aside from stopping the genocide, of course. The UN is already loyally following veto counts, and has made its position on that clear.

- The genocide has not only been of human life. The IOF has succeeded in eviscerating natural landscapes, flora and fauna a swell, deploying on one land mass a total of over 70,000 tons of missiles – a total that exceeds the World War 2 bombings of Dresden, Hamburg, and London combined. Those were different populations enduring bombings over multiple years. These are one people, having to shoulder the brunt of this suffering nonstop, consistently, for what is still under a year. This is sped up and concentrated. If the World War 2 numbers are considered disastrous, inhumane, a lesson to never repeat our mistakes again, unconscionable – then what are we – what is the UN – allowing to happen, at more than triple the pace?Another perspective: Gaza is less than 2/3 the size of Hiroshima, and has been hit with 6 times the impact of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, also in World War 2. What effect could this have on the biodiversity of the region?The accelerated rate of climate change this past year is theorized to be due to Israel’s bombing of Palestine (and the rate its going, Israel’s acts of terrorism against Lebanon) – the first few months’ worth of carbon emissions since October 7th amounting to more than that of 20 nations’ annual output combined. Do these acts not fall under ecoterrorism?

- This is not to mention the fact that a considerable amount of these emissions are caused by US cargo planes, delivering the missiles to Israel. So there is more than one ‘polluter’ who needs to ‘pay.’ The carbon emissions affect not only Palestine, but the world at large. So who must be ‘paid’? To what extent? Who will hold perpetrators of war accountable?

- Does the UN have some sort of response action set in case countries go against agreements they’ve ratified? Will there be any disciplinary action taken against whoever approved the motion to begin the forced evacuation from a children’s hospital of a disabled, 11 years old Yazan Tamimi, a Palestinian refugee who was forced to flee Gaza with his parents, to Iceland. A child in a hospital was woken up in the middle of the night and driven to the airport to be deported. Iceland signed on to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. While Yazan’s case was eventually followed up and he was made to return to the hospital and continue to see medical care for his muscle dystrophy, the fact remains more than one person with power in the country was able to conceive of, relay, approve and carry out the deportation of a sick child who sought refuge from war in the country. More than one person with power defied the UN Convention. What will happen to these abusers of power? And, had the deportation gone through to completion, what action would fall to the UN to take? And would the UN take it?

- Is the UN doing anything substantially long-term – beyond camps – for refugees around the world? It is to be noted that many countries providing safe havens to the refugees fleeing war, civil unrest, upheavals, dissolutions, and the like, have not signed onto the UN Convention on the Status of Refugees. The Conventio0n does not apply to the current realities of regions around the world… non-European regions, in a non-Cold-War time.

With these questions, and this post bearing my contentions with the body that has written a foundational text I needed to study and cover, I’ll take my leave. I hope to return next time, with a look at sustainable development.