Overall Conclusion

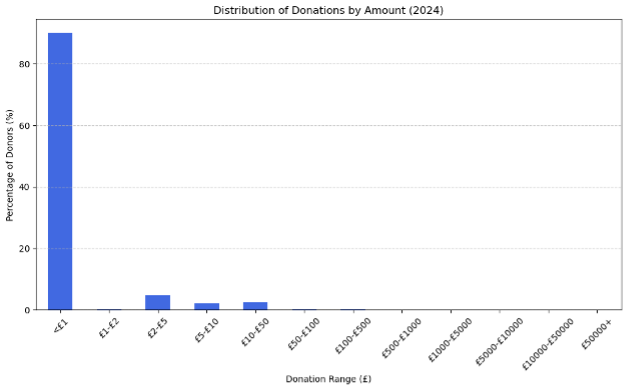

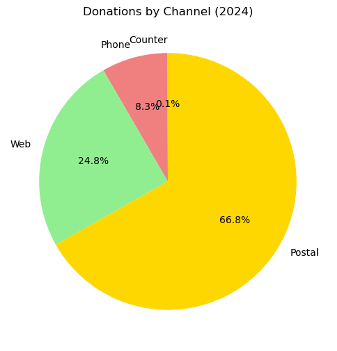

The donation analysis for the Edinburgh International Book Festival in 2024 reveals key trends in donor behavior, fundraising channels, and event-driven contributions. The total donations for 2024 amounted to £538,239.86, distributed across different channels, with postal donations (53.52%) and online donations (39.79%) being the primary sources. Small donations, particularly those under £1, dominate in volume but contribute less to the overall funds, while high-value donations from a small group of donors remain crucial to the festival’s financial health.

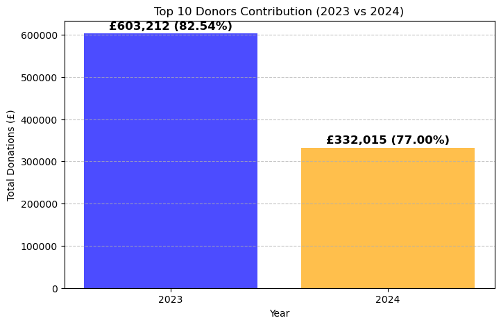

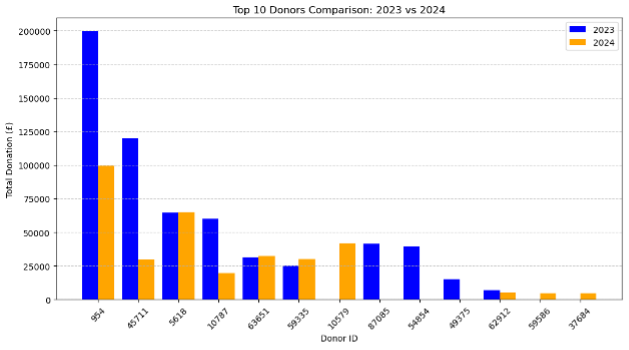

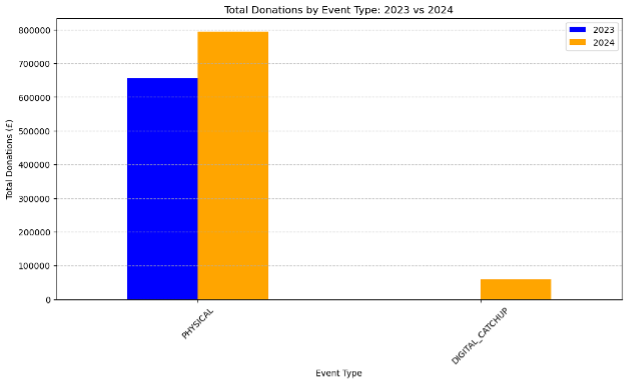

Comparing donation trends between 2023 and 2024, several critical observations emerge:

- A decline in total contributions from the top 10 donors (down from £603,212.31 in 2023 to £332,015.00 in 2024) suggests that major donor retention is a challenge. The absence of some high-value donors from previous years has significantly impacted total fundraising.

- In-person events remain the strongest fundraising avenue, with donations increasing by 21.1% year-over-year. This suggests that live events offer an effective platform for engaging donors and encouraging contributions.

- The introduction of digital replay donations (DIGITAL_CATCHUP) contributed £58,988.04, a promising new revenue stream. This indicates that digital engagement could play a larger role in future fundraising.

- Donation frequency per donor remained largely unchanged, implying that most donors contribute only once per year. Encouraging repeat donations through sustained engagement strategies is a key area for improvement.

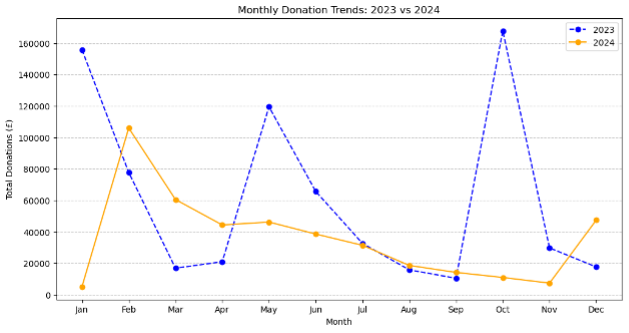

- Fluctuations in monthly donation trends suggest that fundraising efforts were not evenly distributed across the year. Significant drops in January (-96.71%) and October (-93.44%) highlight periods of weak engagement, whereas spikes in March (+258.06%) and December (+168.94%) indicate successful seasonal or event-driven campaigns.

- New donors increased by 35% in 2024, but their average contribution was significantly lower than that of returning donors. This suggests that while outreach efforts successfully attracted new donors, retention and engagement strategies need to be improved to convert them into long-term supporters.

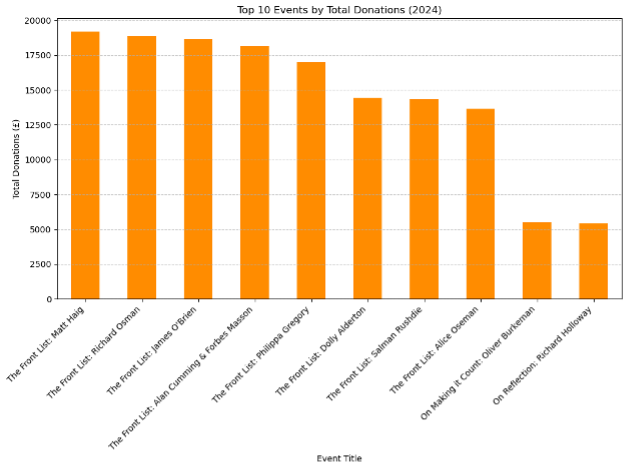

- Not all events contribute equally to fundraising. The “Front List” series proved highly effective in generating donations, whereas children’s events and some online events received little to no financial support.

To build on these findings, the festival should adopt a multi-faceted donation strategy that strengthens donor retention, expands digital fundraising, and optimizes fundraising opportunities across all event types.

Recommendations and Fundraising Strategies

1. Strengthening Major Donor Retention

- Personalized Engagement: High-value donors play a disproportionately large role in total contributions. Implementing a dedicated donor relationship management program that includes personalized thank-you messages, exclusive event invitations, and tailored engagement plans can help retain and grow this segment.

- Exclusive Recognition and Benefits: Introduce “Patron Circles” or VIP tiers that offer perks such as exclusive author meet-and-greet sessions, premium seating, and behind-the-scenes festival access to encourage repeat and larger donations.

- Matching Gift Campaigns: Partner with corporate sponsors to offer matching donations for high-value contributors, effectively doubling the impact of their contributions.

2. Enhancing Small and Mid-Level Donor Engagement

- Optimized Suggested Donation Tiers: As 90.06% of donations are under £1, implementing a structured tiered donation system (e.g., £2, £5, £10 as default choices) can help increase the average contribution per donor.

- Gamification and Incentives: Introduce a “Supporter Badge” system, where donors receive digital or physical recognition for reaching cumulative donation milestones.

- Recurring Giving Options: Encourage donors to sign up for monthly giving programs by highlighting the long-term impact of their support and offering small perks for participation.

3. Expanding Digital and Online Fundraising

- Enhance Digital Replay Monetization: Given that DIGITAL_CATCHUP raised £58,988.04 despite being a new initiative, further investment in paywall options, donation prompts before accessing content, or exclusive replay content for donors can significantly increase this revenue stream.

- Live Donation Appeals During Events: Implement real-time fundraising drives during online events, with visible donation progress bars and live acknowledgments for contributors.

- Social Media Donation Challenges: Run targeted digital fundraising campaigns, such as “30 Days of Reading – Support the Festival”, encouraging donors to participate and share their contributions on social platforms.

4. Optimizing Event-Based Fundraising Strategies

- Leverage High-Performing Events: Events such as the “Front List” series generated significant donations (up to £19,178.50 per session). These events should be expanded with dedicated fundraising messaging and premium donation incentives.

- Improve Fundraising for Children’s and Online Events: Children’s events received minimal donations. Adding a “Parent Sponsorship” model, where parents can contribute to literacy programs or subsidized tickets for disadvantaged children, could bridge this gap.

- Festival-Wide Fundraising Integration: Ensure that every festival event includes a donation pitch at the beginning or end, with clear instructions on how to give.

5. Timing and Campaign Planning

- Address Seasonal Donation Drops: The steep declines in donations during January, October, and November indicate gaps in fundraising efforts. Introducing winter fundraising campaigns, anniversary fundraising drives, or pre-event donation challenges could help smooth out donation volatility.

- Leverage Successful Seasonal Spikes: Since March and December showed strong donation surges, running complementary early-bird fundraising initiatives, holiday-themed giving campaigns, or exclusive seasonal perks could further maximize revenue.

Final Thoughts

The Edinburgh International Book Festival has a unique opportunity to optimize its fundraising strategy by leveraging event-driven donations, expanding digital engagement, and strengthening donor retention efforts. While in-person events remain the primary driver of contributions, digital replay donations offer a promising new revenue stream. Addressing disparities in event-based fundraising, refining seasonal donation strategies, and enhancing engagement for both high-value and small donors will be key to ensuring long-term financial sustainability and growth.

By implementing these targeted strategies, the festival can increase donor retention, boost donation amounts across all levels, and future-proof its fundraising efforts in an evolving digital landscape.

Key Findings:

Key Findings: