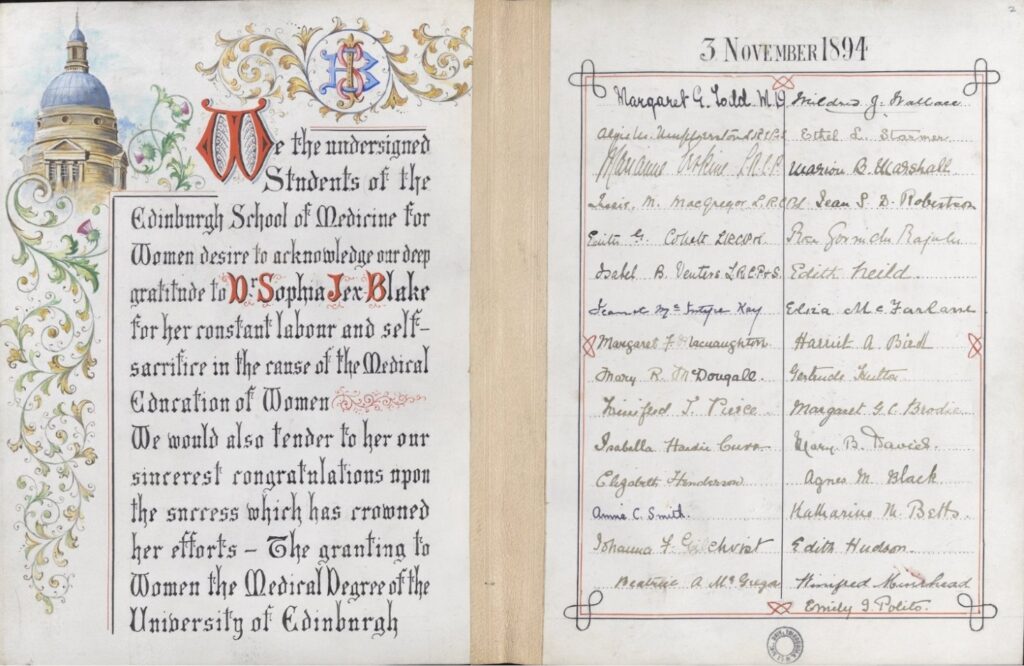

Certificate Presented to Sophia Jex-Blake, Dc.3.103, 1894.

In the context of Orientalism and white patriarchal centrism, the European and Northern American worlds occupied absolute superiority in the depiction of art history. Art historians have portrayed the exotic Oriental world with extraordinary imagination. They carried out indiscriminate colonisation of Africa, Oceania and Asia to establish a global colonial history and artistic history that belonged to Europe. Consequently, throughout the over 500 years of colonisation, people have grown accustomed to narratives based on Western perspectives. As the notion of post-colonialism emerged, scholars turned to another way of approaching artistic history. They came up with new ideas, such as the history of feminism being excluded from Western art history (Linda Norchlin) and the Third World having its own biennial/triennial. The nation, state, and national culture should become possible (Geeta Kapu). While museums and galleries have started to rectify this perception in the twenty-first century, it is not negligible that there is no “pure” oppositional practice vis-a-vis the contemporary museum, nor museological context wholly uncontaminated by the circuits of capitalism or the history of the power of the western museums.

The traces of colonialism in contemporary museums/galleries are somewhat less evident than in more established museums such as the British Museum, where they may appear not necessarily in the categories and origins of the collections but also in the museum/gallery architecture. The Talbot Rice Gallery was built on the former Natural History Museum site at the Old College. Before that period, as the Natural History Museum, the space was imbued with a sense of colonial narrative, and its collections were sourced from all over the world. During his 50 years as director of the museum, collectors like Robert Jameson used his connections to bring in a vast array of plant and animal specimens, most notably platypus specimens and a live puma. It might seem like for a first-time visitor to Talbot Rice Gallery, when we come across the puma and platypus signs, we feel confused and do not understand why a modern, contemporary gallery would have a plush animal that should be part of a history museum. When I first stepped into Talbot Rice Gallery and tried to understand the story behind the gallery, I was also plagued by this little problem.

The Talbot Rice Gallery, re-established in 1975, no longer holds these colonial artefacts; the collection has long since been transferred to the National Museum of Scotland. In recent years, Talbot Rice Gallery’s exhibitions have been devoted to contemporary and futuristic art, depicting themes ranging from geography and nature to women and the surreal, and the colonialist ethos has been undermined by a new practice of modern and contemporary art. However, as we step into the gallery space, the domed roof, the honeysuckle flower frieze adorning the columns and the Doric order can be seen as traces of the architect’s fetish for aesthetically appealing orientalism. But suppose more clues and stories are waiting to be uncovered when we gather our attention to the colonial traces in these buildings.

Furthermore, as the Enlightenment-influenced pioneering thinking spread to Edinburgh, there was an emerging number of scholars, such as the renowned philosopher David Hume, who studied at the University of Edinburgh and started his philosophical career there. These brilliant scholars came together at Old College, Edinburgh University, and undertook to establish a new educational and scientific framework for the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas. However, its legacy regarding women’s education tells a different story- one marred by discrimination, exclusion and discrimination, the other marred by the lack of a proper education. One marred by discrimination, exclusion, and resistance to change.

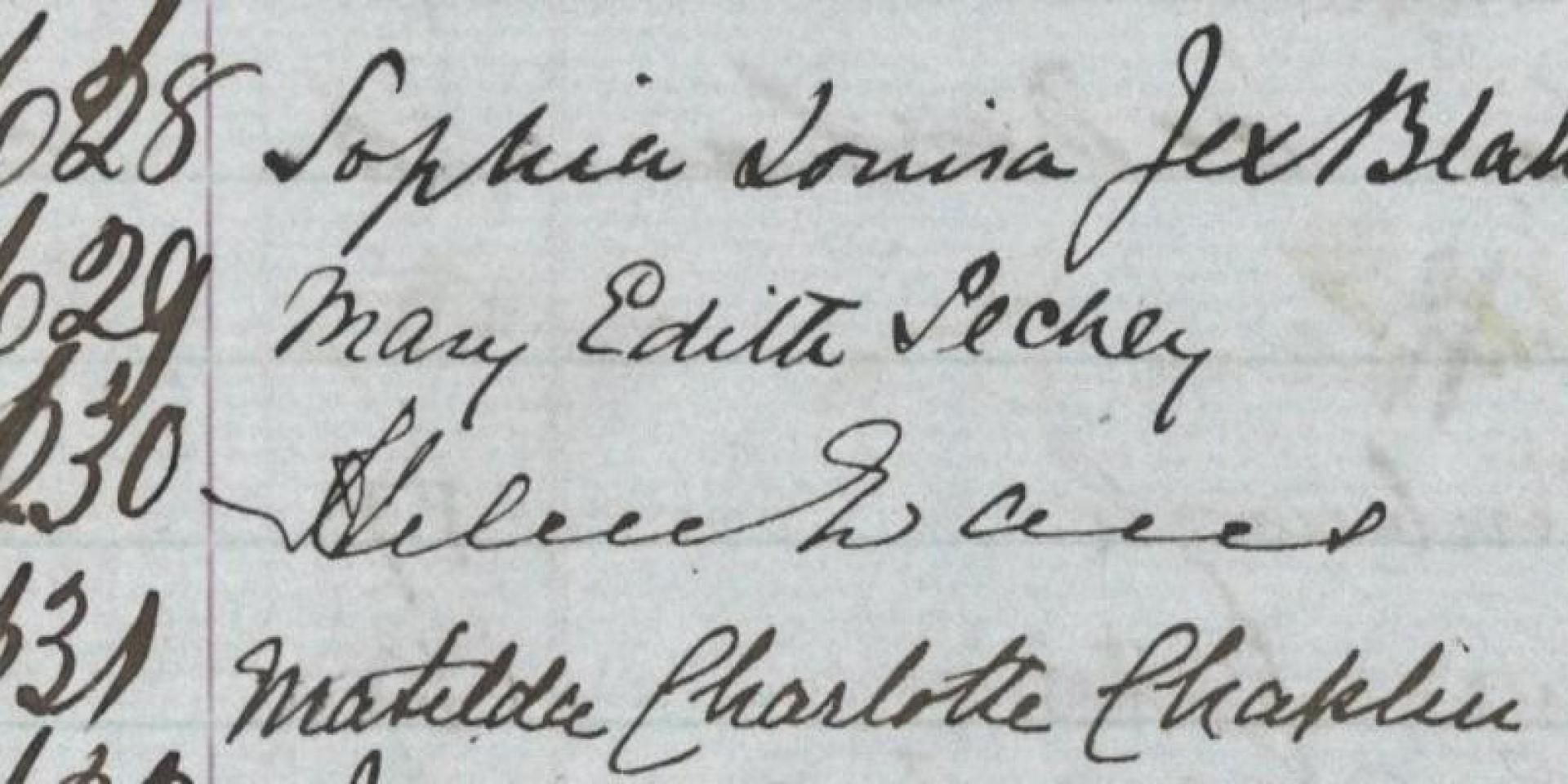

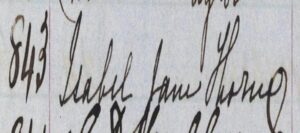

Female Students like Sophia Jex-Blake applied to the University of Edinburgh during the middle of the nineteenth century. The Academic Committee initially rejected the application for reasons of her gender. Sophia embarked on a lifelong campaign, starting with her application for a place in the university. Inspired by David Masson and David Russel, she resorted to advertising to the Scotsman to encourage more women to apply. She delivered multiple applications to the university to secure a place. She successfully managed to recruit more women students to join her team: Edith Pechey, Isabel Thorne, Emily Bovell, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, and Mary Anderson, whom we call Edinburgh Seven.

Matriculation Signatures: Sophia Lousia Jex-Blake , Mary Edith Pechey, Helen Evans. Matilda Charlotte ChaplinMatriculation Roll, 1861-1874 EUA IN1/ADS/STA/2

Matriculation Record, Isabel Thorne. University of Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections. Matriculation Roll, 1861-1874

As a matter of fact, women confronted difficulties at the step of enrolment only, not to mention the challenges of attending the university while studying. The main perpetrators of these difficulties are male students who had brought difficulties to female students. They disrupted female students’ exams, constantly threatened them with expulsion, and sent them countless obscene messages and profanities in the mail.

In the Enlightenment-inspired hall of the Old College, these forms of inequitable gender discrimination were allowed to exist and develop with impunity. The Universities (Scotland) Act of 1889 gave more autonomy to the regional universities in Scotland, and the terms of the law helped pave the way for women to attend the universities. In 1892, following the provisions of the Act and the pioneering work of Sophia and other women, Scottish universities finally allowed women to be enrolled. This initiative gave universities a more extensive resource of talented students, which resulted from Sophia and others fighting for women’s access to education. When we appreciate Old College through the viewpoint of educational development, we can read the story of liberalisation and gender equality in this structure. While the Old College eventually opened its door to women, its history reflects a broader resistance pattern to equality and diversity. As we look back at the stories behind the architecture and history of the Old College, we continue to deepen the remarkable story of our forefathers’ decolonisation and struggle for gender equality.

Bibliography:

Kapur, Geeta. “Strategies for Curating in the Postmodern Scenario.” Art India 4, no. 2 (1999): 50.

Mathur, Saloni. “Social Thought & Commentary: Museums Globalization.” Anthropological Quarterly 78, no. 3 (2005): 697-708.

Morris, William Edward, and Charlotte R. Brown. “David Hume.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2001.

Butler, Josephine, ed. Woman’s Work and Woman’s Culture: A Series of Essays. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Roberts, Shirley. “Blake, Sophia Louisa Jex- (1840–1912).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Roberts, Shirley. Sophia Jex-Blake. London: Routledge, 1993.