📚 Learning Applied: Budget as Critical Practice

From W4 and W11, I began to rethink budgeting not as an administrative task, but as a curatorial decision-making tool.

In W4, Gabi’s session on relational ethics challenged me to consider:

Who is being paid? Who is contributing without recognition? Who has the power to say no?

This directly shaped my approach to volunteer honoraria, where I included line items for cross-school collaborators and student assistants. Rather than assume goodwill, I translated co-labour into financial and material recognition.

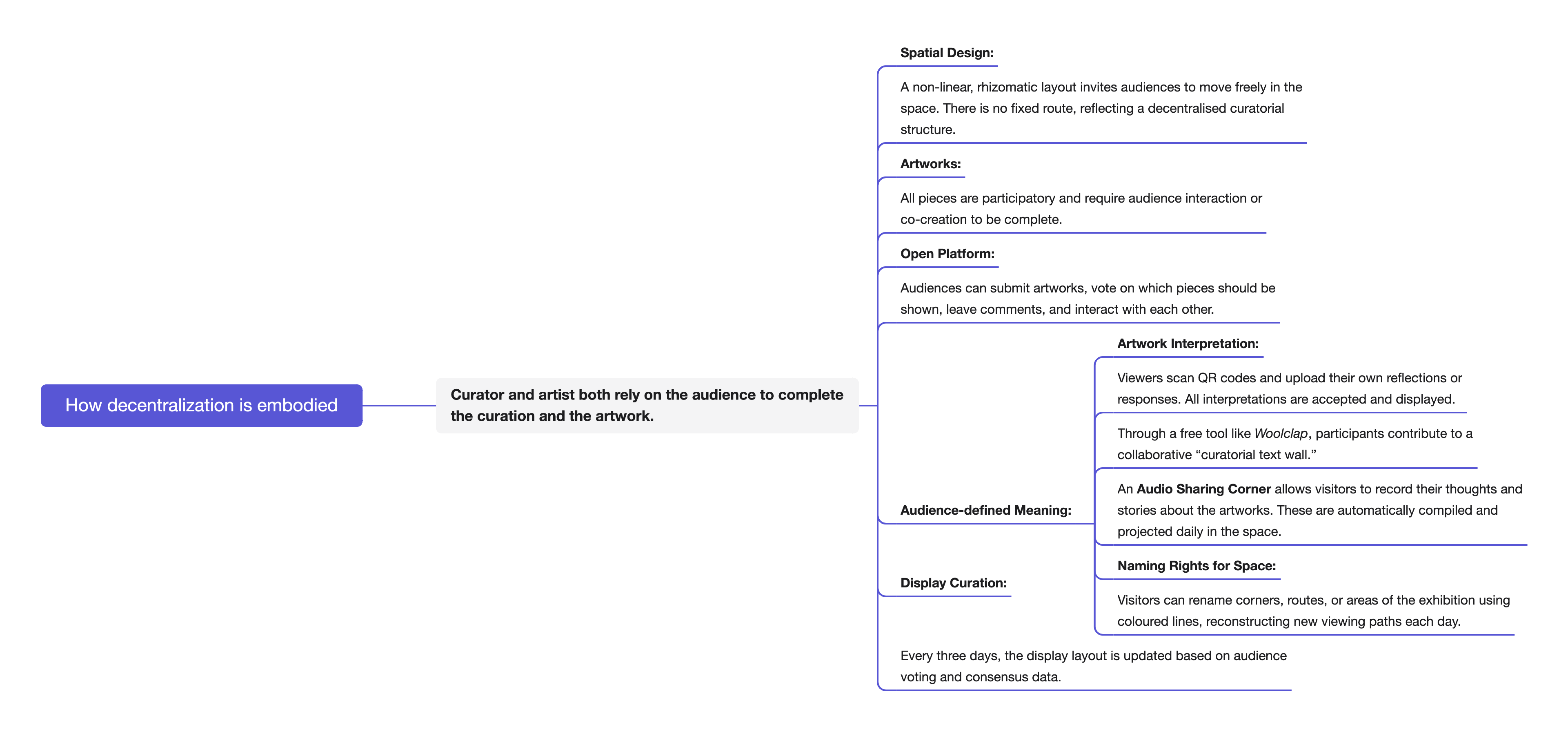

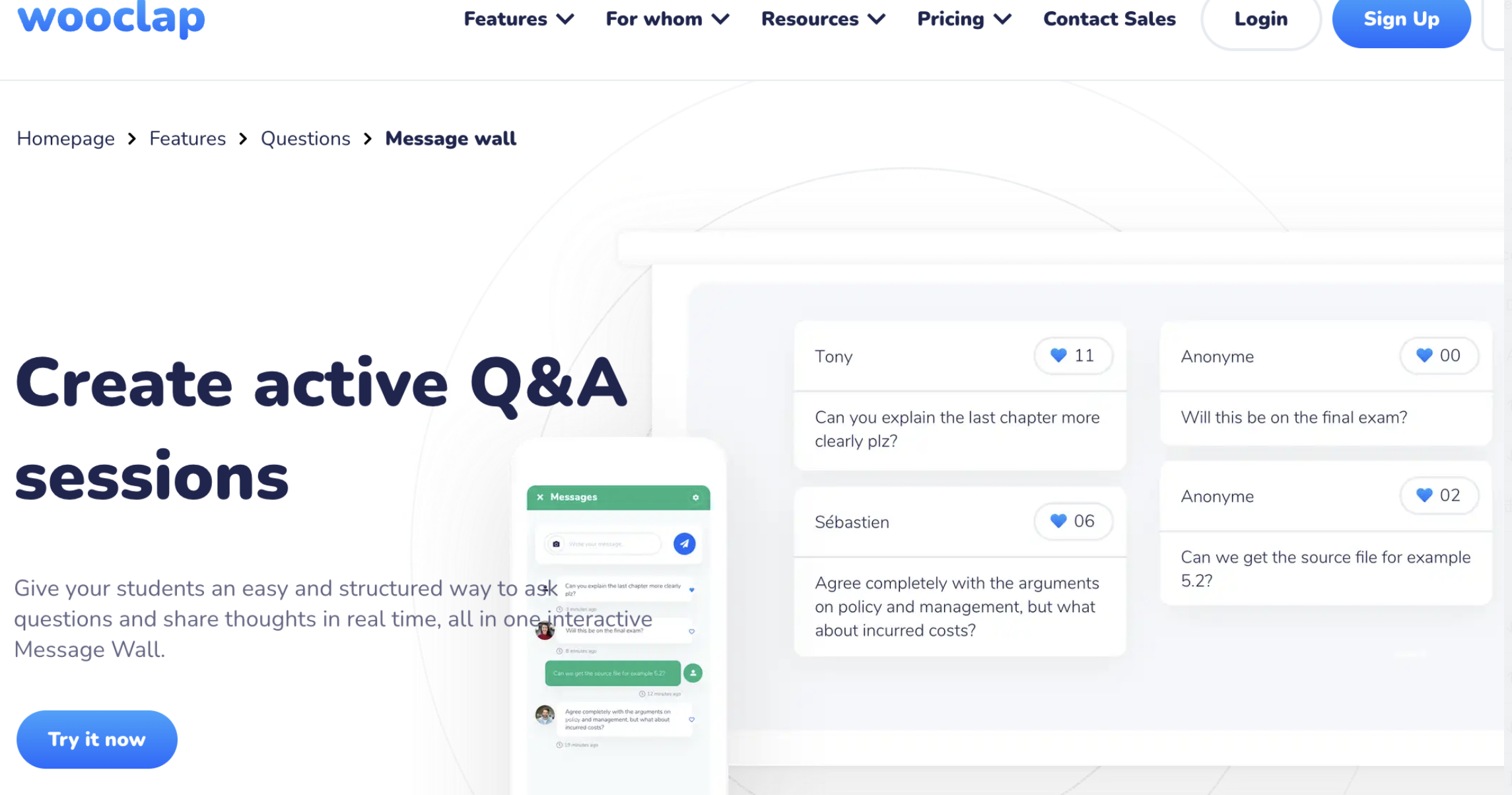

From W11, I drew from our discussions on “scaling through tools” instead of scale through budget. I chose platforms like Woolclap not only because they were free, but because they aligned with the values of open authorship, anonymous contribution, and decentralised control.

The budgeting process became a way to embody my values:

-

Transparency over spectacle

-

Collaboration over outsourcing

-

Access over exclusivity

By the end, every cost wasn’t just a line item—it was a reflection of curatorial ethics in action.

I kept my budget strictly within £2000, guided by a resource-sharing ethos that prioritises low-threshold access, intra-school collaboration, and sustainability.

📊 Budget Strategy: Resource-Conscious, Ethically Aligned

Funding comes from three key sources:

- 🏛 EUSA Development Fund (£500)

“The Student Opportunities Fund supports students to deliver events, activities, and projects with community impact.”

EUSA Funding - 🌍 Creative Scotland Open Fund for Individuals (£1300)

“Supporting a wide range of activity initiated by artists, writers, producers and other creative practitioners in Scotland.”

Creative Scotland Funding - 💡 Own Contribution (£200) — allocated toward zine printing, design materials, and micro-gifts.

Infrastructure, Not Decoration

The exhibition’s physical and interactive design was shaped around necessity:

- The site—ECA Main Hall—is an open-access, in-kind supported venue.

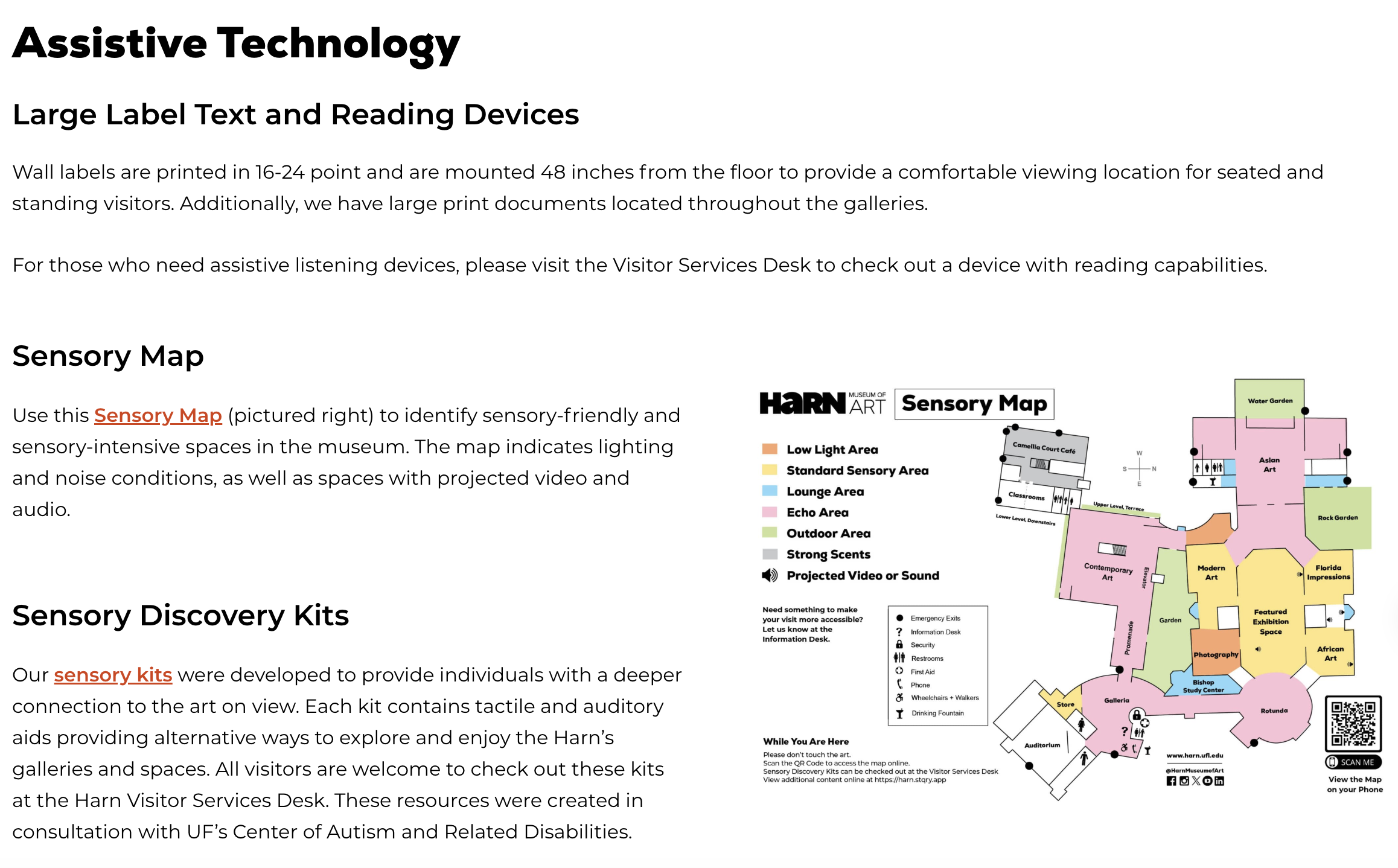

- TESOL & Inclusive Design students designed multilingual signage and accessibility prompts.

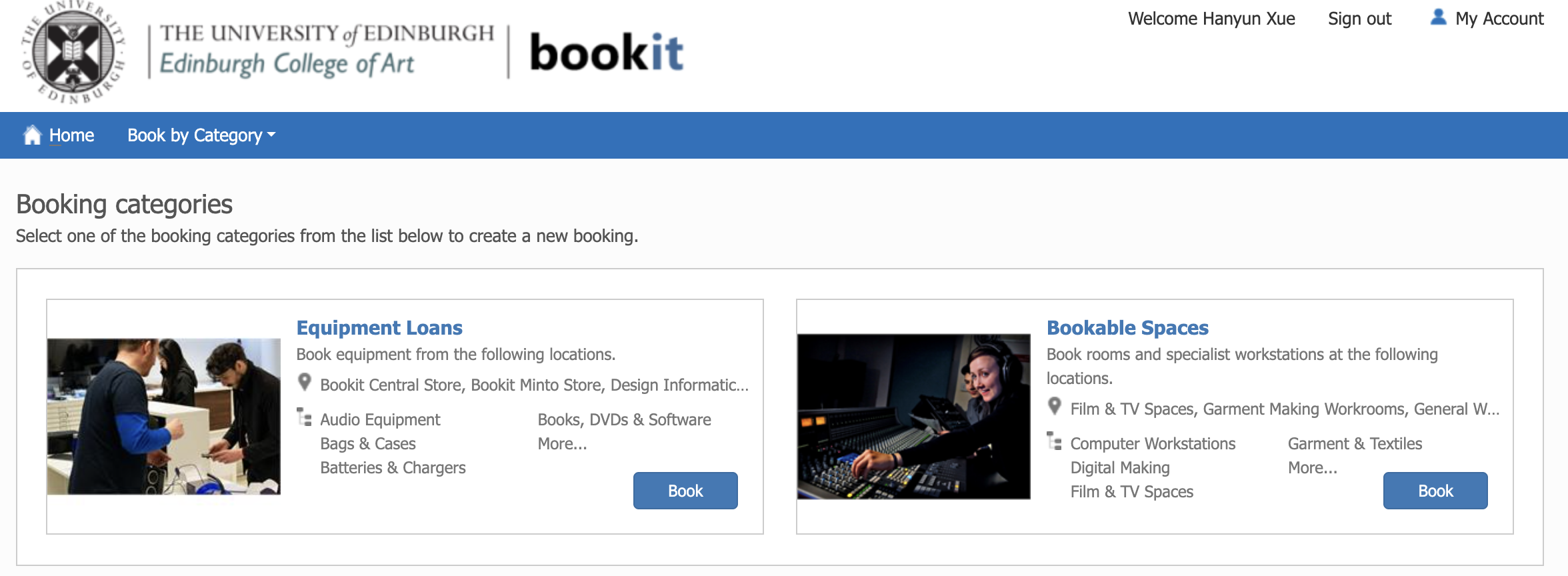

- ECA Bookit resources (recorders, polling boards) and digital screens were integrated, avoiding extra rental costs.

- CAP student works form the core of the exhibition content—no artist fees required.

Shared Tools, Shared Authorship

Interactive systems were built with open-source platforms like Woolclap, allowing anonymous input, multilingual co-writing, and slow-tech responses.

Equipment such as cameras, screens, and sound systems were borrowed within the school ecosystem.

The exhibition is digitally inclusive without becoming digitally exclusive.

Cross-School as Co-Labour

Collaboration was budgeted as co-authorship:

- 5 cross-school units were supported (Design, TESOL, Education, Art History, CAT).

- Volunteer honoraria and co-creation materials were included to ensure commitment was recognised.

Micro is Sustainable

Rather than scale through money, I scaled through imagination and alliances.

No hired install crew. No designer fees. Instead: a network of student collaborators and shared responsibility.

The budget became a curatorial medium—reflecting my ethics, values, and sense of what must be shared, and what can be let go.

Approx. £450 of this is in-kind support (space, equipment, co-curation labour).

24.3% of the budget reflects shared resources—not as a compromise, but as a commitment to an open, collaborative curatorial ecology.

(ECA Request Flow Diagram for ART/DESIGN/ESALA requests)

Selected Budget Breakdown

| Category | Description | Cost (£) |

| 🟡 Exhibition Design & Space | Infrastructure materials: paths, sound corners, book walls, naming stickers, maps, feedback boards | 300 |

| Printing multilingual guides & signage (designed with TESOL/Inclusive Design students) | 100 | |

| Sensory alternatives: carpets, cushions, tactile zones, quiet signage | 100 | |

| 🟡 Interactive & Co-Creation Tools | Woolclap platform use (free) + setup costs: QR codes, stands | 100 |

| Polling wall, co-writing sticky notes, voice corner setup (recorder rental, feedback system) | 100 | |

| 🟡 Promotion & Design | Social media visuals, copywriting, scheduling | 50 |

| Print guidebooks & resource kits (for Art Ed / TESOL school tours) | 100 | |

| 🟡 Post-Exhibition Outputs | Curatorial Zine printing (co-written texts, audience quotes, 80 copies @ £2.5) | 200 |

| Data visualisation + Participation Trends Report | 50 | |

| 🟡 Personnel & Collaboration Support | CAP student install/travel support | 100 |

| Cross-school volunteer honoraria (10 x £20) | 200 | |

| Trained facilitators for blind/deaf visitors, water points, seating | 100 | |

| 🟡 Public Programme | Public Talk Setup + Tea Reception (“On Shifting Curatorial Power”) | 100 |

| Materials for “co-curation” workshop + print souvenirs (e.g. postcards) | 100 | |

| 🔵 Contingency | Emergency repairs, tech replacements, on-site staffing | 150 |

| 💡 TOTAL | £2000 |

![Home [www.victoriesnautism.com]](https://th.bing.com/th/id/R.b8f4afd386a99f83da117cdc1585f9ed?rik=NFwJMjNv3U0pLw&riu=http%3a%2f%2fwww.victoriesnautism.com%2fuploads%2f4%2f0%2f4%2f0%2f4040527%2f9118470_orig.png&ehk=vzG%2bDm1Bh231I9%2flBWhKI2EQ77dMYvfxNX%2bAa7s1IoY%3d&risl=&pid=ImgRaw&r=0)

(Myзeй coвpeMeHHoгo иcKyccтвa -Participatory Art Practices)

(Myзeй coвpeMeHHoгo иcKyccтвa -Participatory Art Practices) (How to… Curate Participatory Art Projects – Schools and Teachers

(How to… Curate Participatory Art Projects – Schools and Teachers

(Accessibility-Inclusive Art Museum -Harn Museum of Art)

(Accessibility-Inclusive Art Museum -Harn Museum of Art)

Rather than assigning movement, I invite navigation. This aligns with ideas explored in

Rather than assigning movement, I invite navigation. This aligns with ideas explored in

🌊 My Exhibition Is Not a “Finished Product,” But a Flowing Relationship

🌊 My Exhibition Is Not a “Finished Product,” But a Flowing Relationship