Part 1:

Introduction

Before anything else, let me show you what we made.

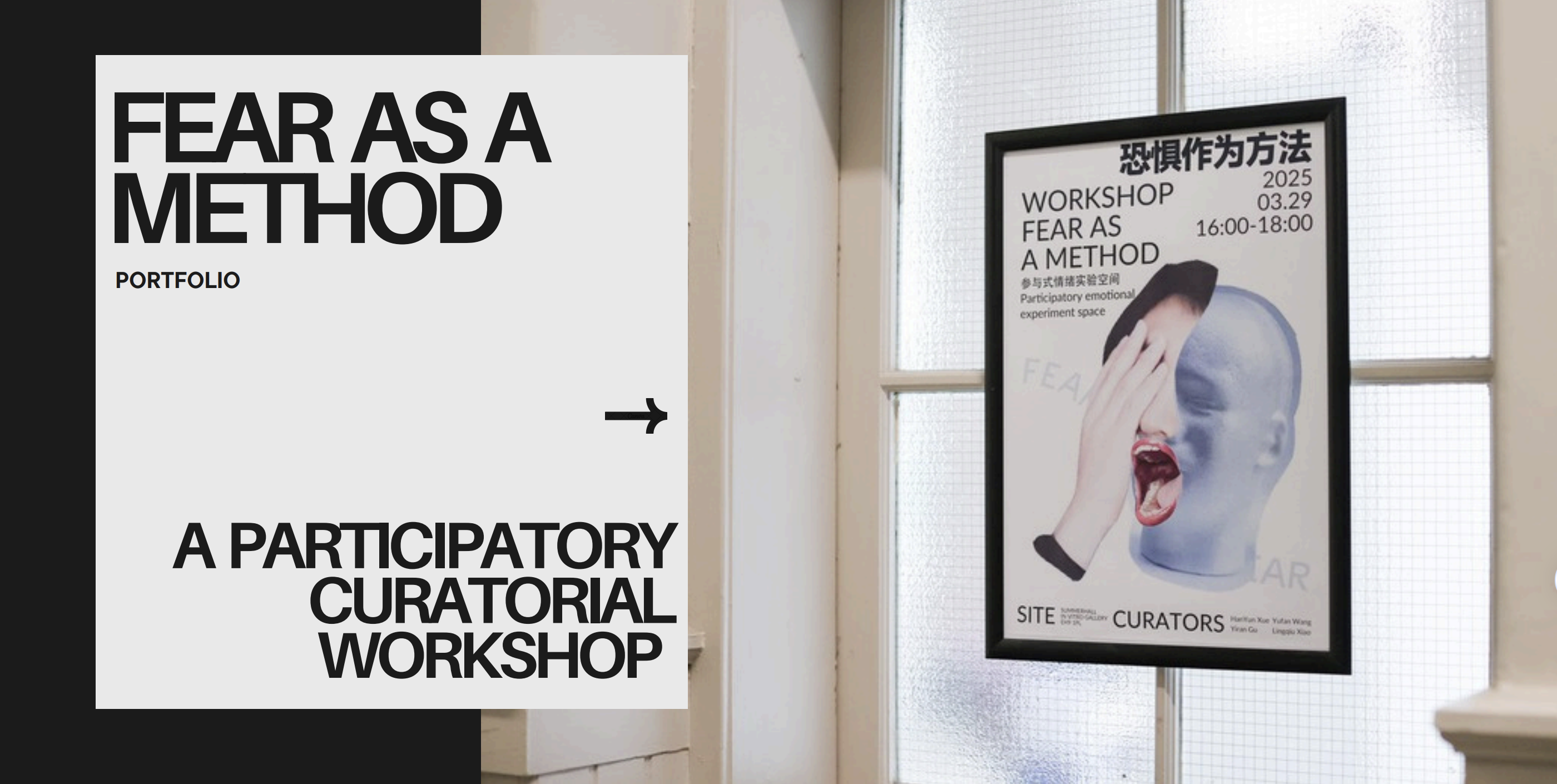

This is the title slide from our final curatorial presentation:

Please click the link to view

Fear as a Method

link:https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/s2500923_curating-2024-2025sem2/wp-content/uploads/sites/11192/2025/04/Fear-as-a-Method.pdf

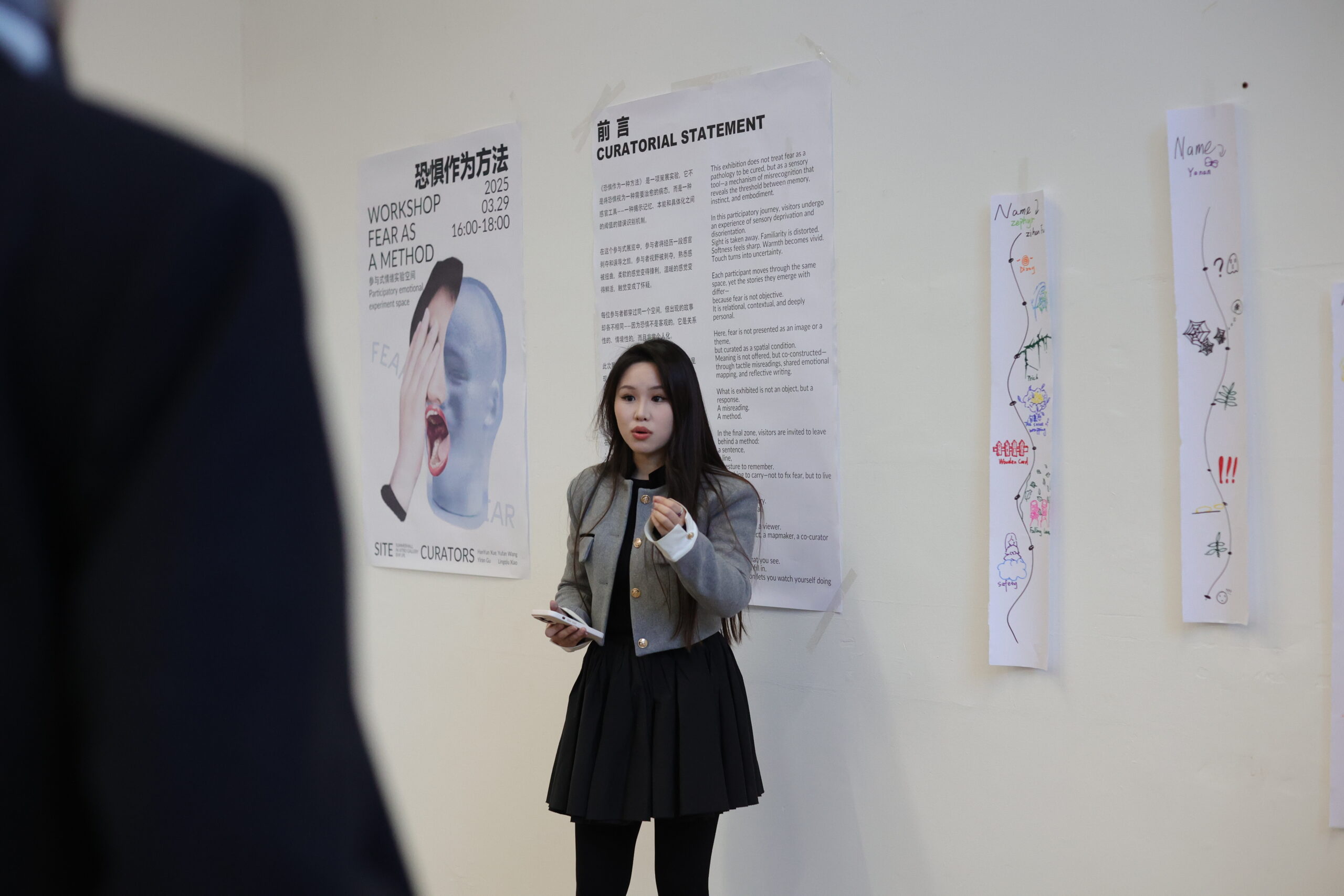

(Fear as a Method A sensory workshop. March 29, 2025 · Summerhall · In Vitro Gallery)

Our PPT laid out the structure, intent, and emotional architecture of the workshop.

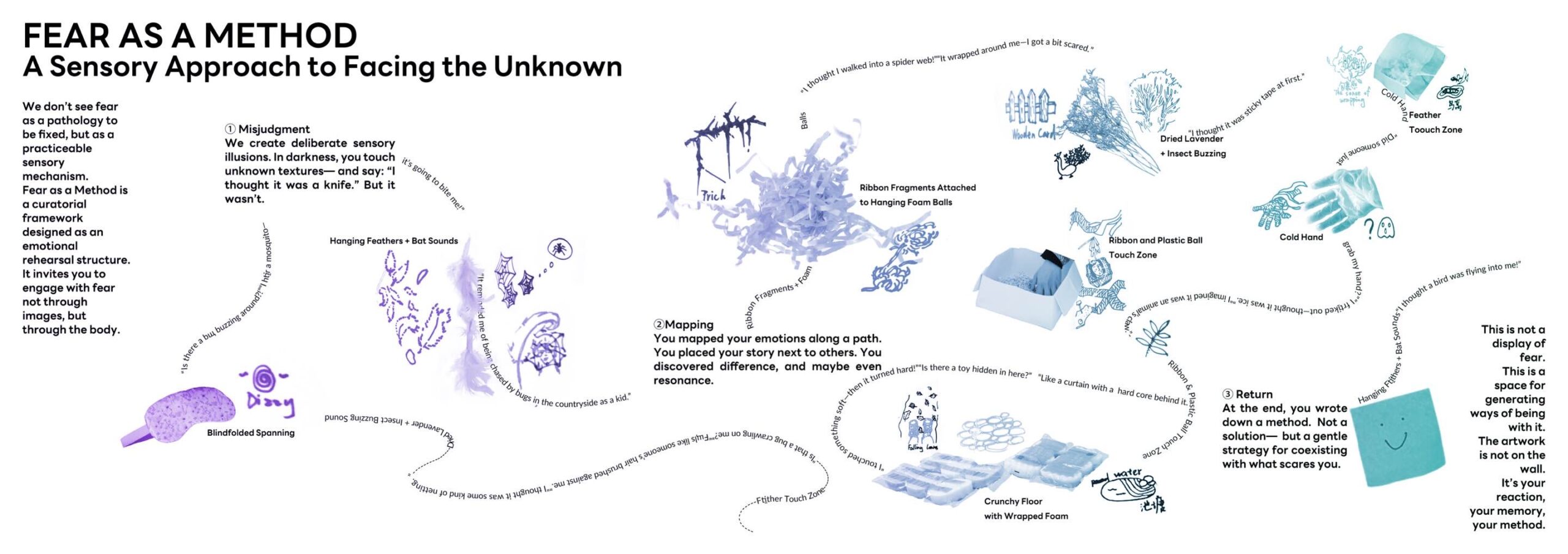

We framed fear not as pathology but as a method—

a curatorial tool to explore perception, misjudgment, and emotional co-creation.

We offered no art objects. No polished installations.

What we gave participants was a guided pathway—

through touch, sound, spatial disorientation, and quiet reflection.

They left not with answers, but with a method.

And we, as curators, left with better questions.

This blog is a reflection on how that happened.

Not just how we built the workshop,

but how the workshop built us.

Part 2:

Curatorial review and reflection

I. Where It All Began: Feeling Our Way Into a Method

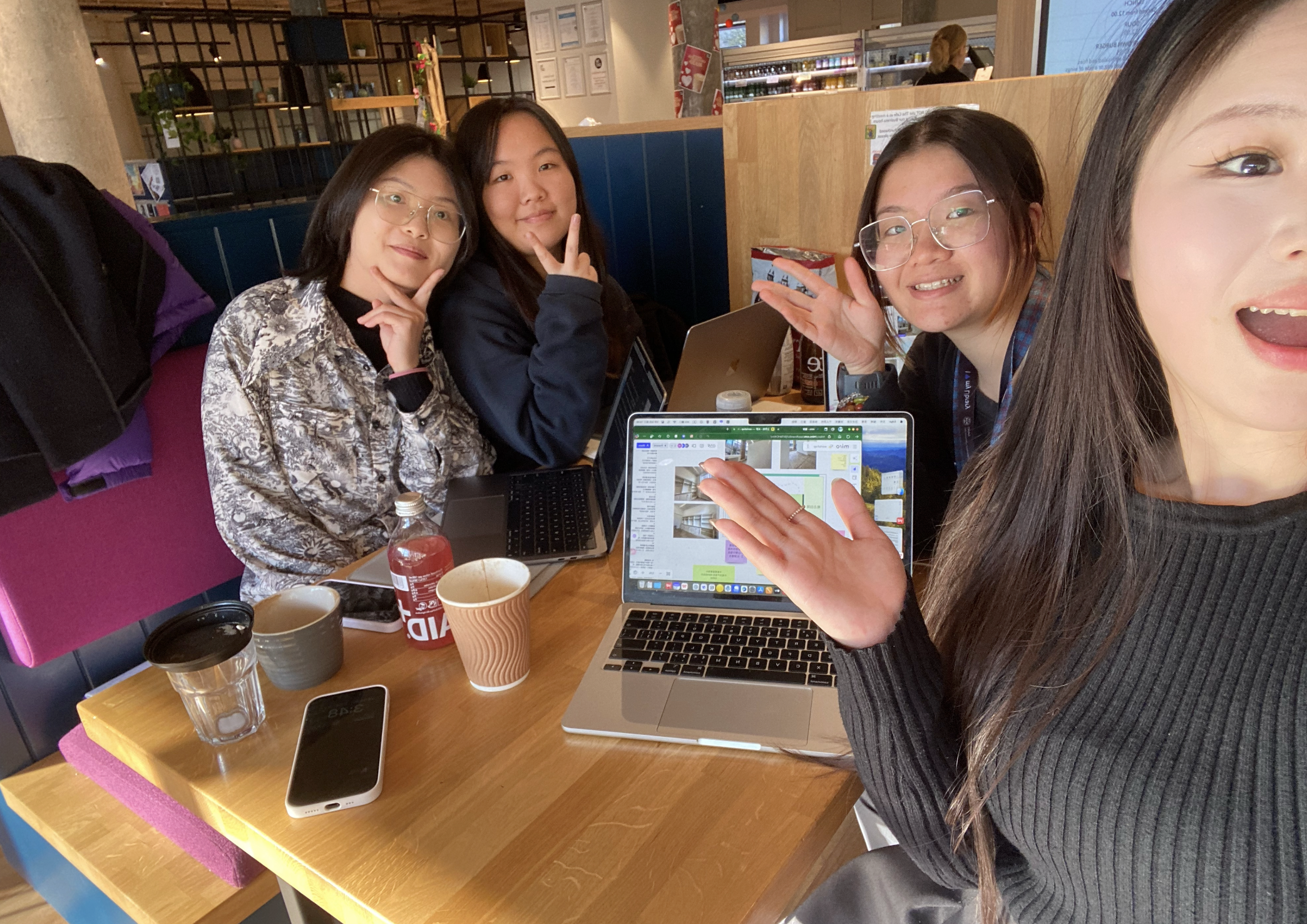

We didn’t begin with a perfect concept. We began with a shared feeling—something more like a hunch than a plan.

It was early March, and the four of us—Yiran, Yufan, Lingqiu, and I—were tucked into a quiet café corner, half-lost in conversation, half-sketching thoughts onto napkins. What kept coming up was this strange, slippery word: fear. Not as an idea to explain, but as a sensation we couldn’t quite pin down. I remember looking up and asking:

“What if fear isn’t something we display, but something we practice—something we can stay with, even gently rehearse?”

And that was it. That question became the doorway to everything that followed.

Right from the beginning, I didn’t want to make an exhibition people only looked at. I wanted to make something people felt through. We proposed the central theme—Fear as a Method—as a way to move away from visuals, and into something more internal: a participatory, sensory, body-centered experience. Not therapy. Not theatre. Just a quiet space where people could encounter their fear—not to fix it, but to understand it differently.

II. Building from the Course: Three Weeks that Shaped Everything

W4: Curatorial Ethics

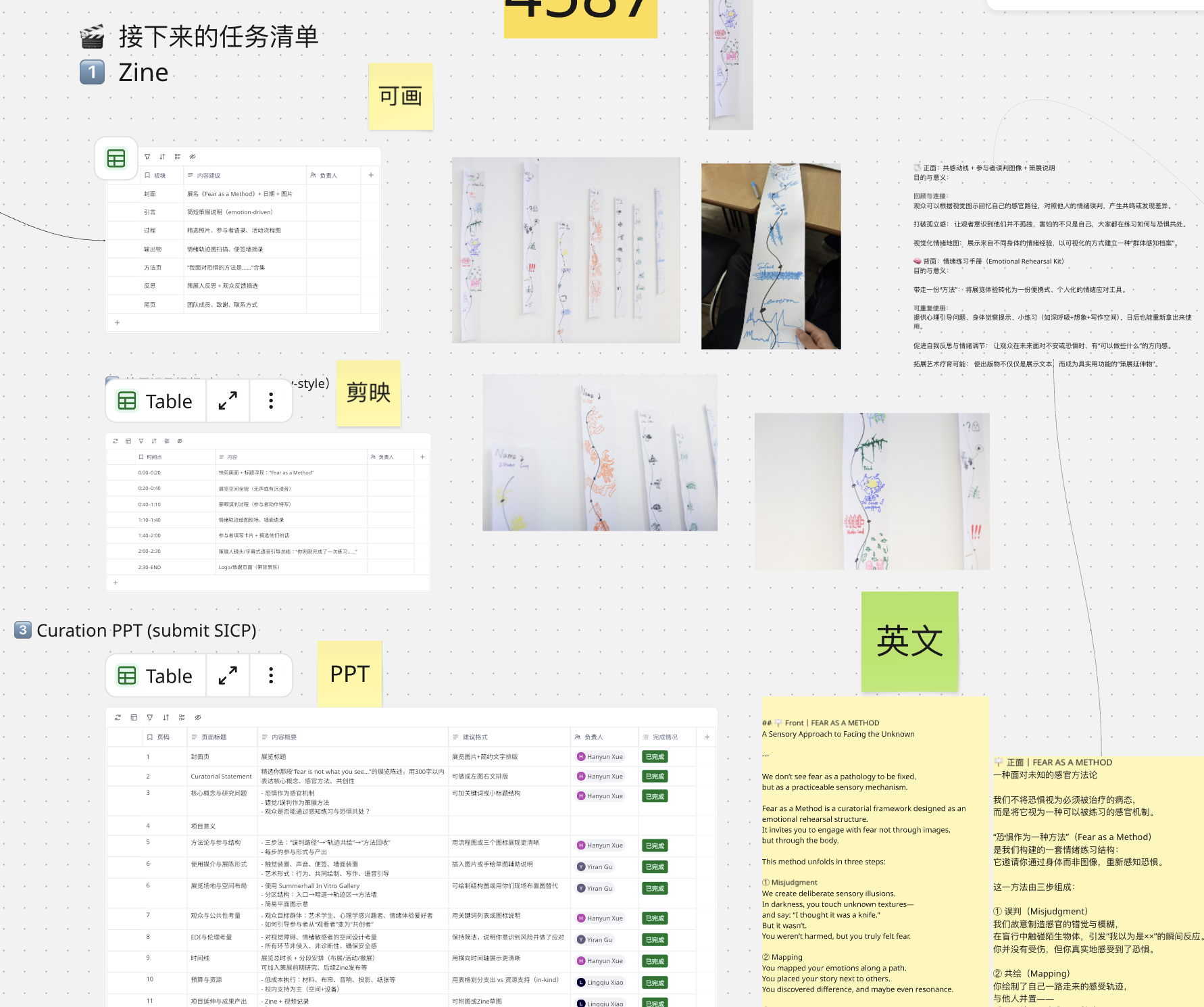

This week changed our entire approach to curating. It taught our to think not only about what we show, but how people feel when moving through a space. Inspired by course readings on care, vulnerability, and bodily safety (O’Neill, Wilson), We began designing the workshop route not as a gallery but as an emotional threshold.

I made key decisions here:

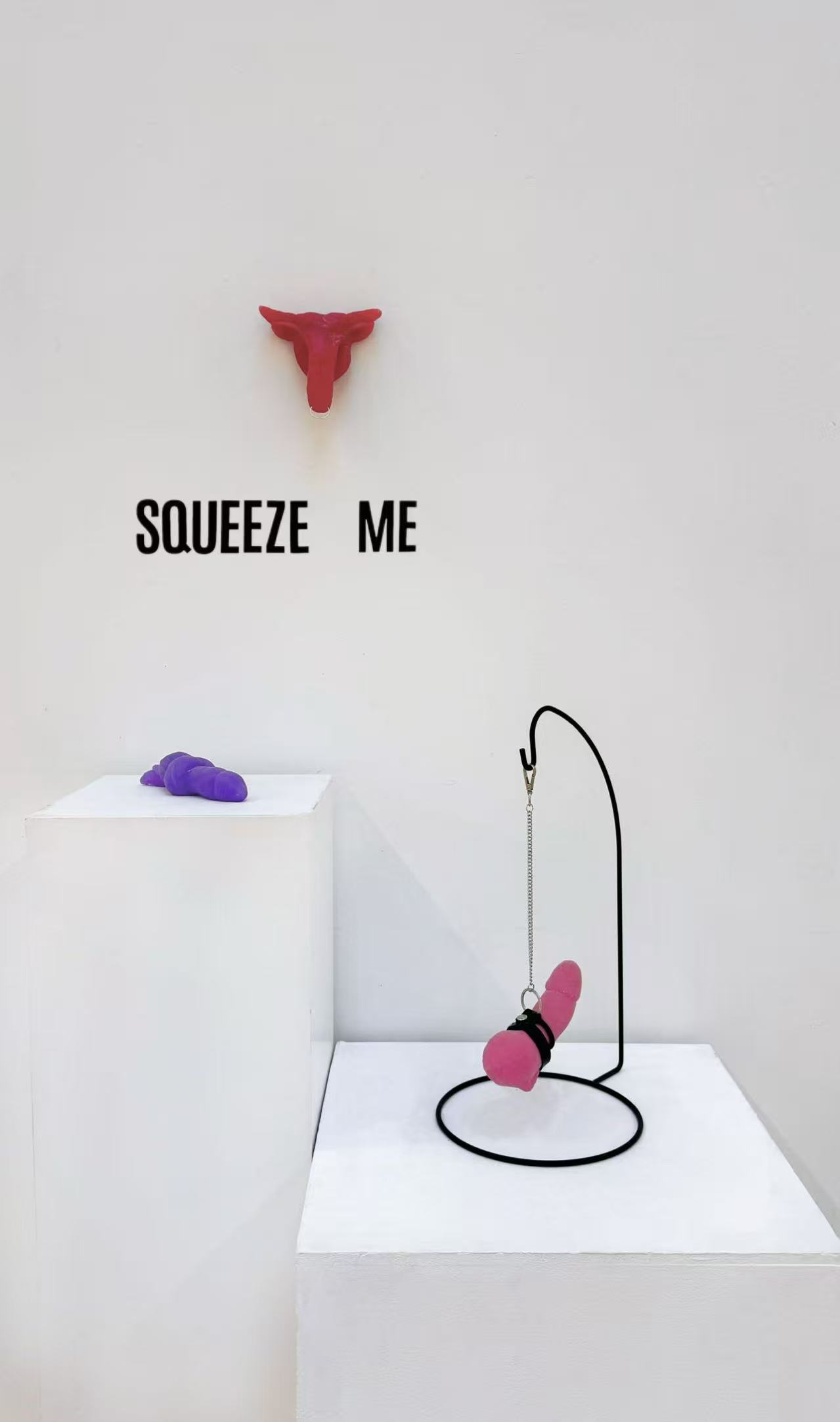

- Using soft materials like feathers and ribbon to create sensory ambiguity.

- Incorporating ambient sound layers that blend comfort and tension.

- Emphasizing psychological safety while gently pushing discomfort.

Our route was not designed for clarity, but for internal resonance.

(The photographer of the event photos: Yiran Gu)

(The photographer of the event photos: Yiran Gu)

W6: Artist-led Curation

This week’s examples reminded me that a curator can also be a facilitator, a host, or a listener. I saw the power of allowing others to co-create the emotional temperature of a project.

We structured the workshop so that each participant could move at their own pace, in silence, blindfolded, uninterrupted. I personally designed the route flow and sound transitions to support this rhythm, ensuring people could drift inward.

During testing, I adjusted the transitions between sensory stations based on what participants felt—not what we expected. My role became not just designer, but emotional cartographer.

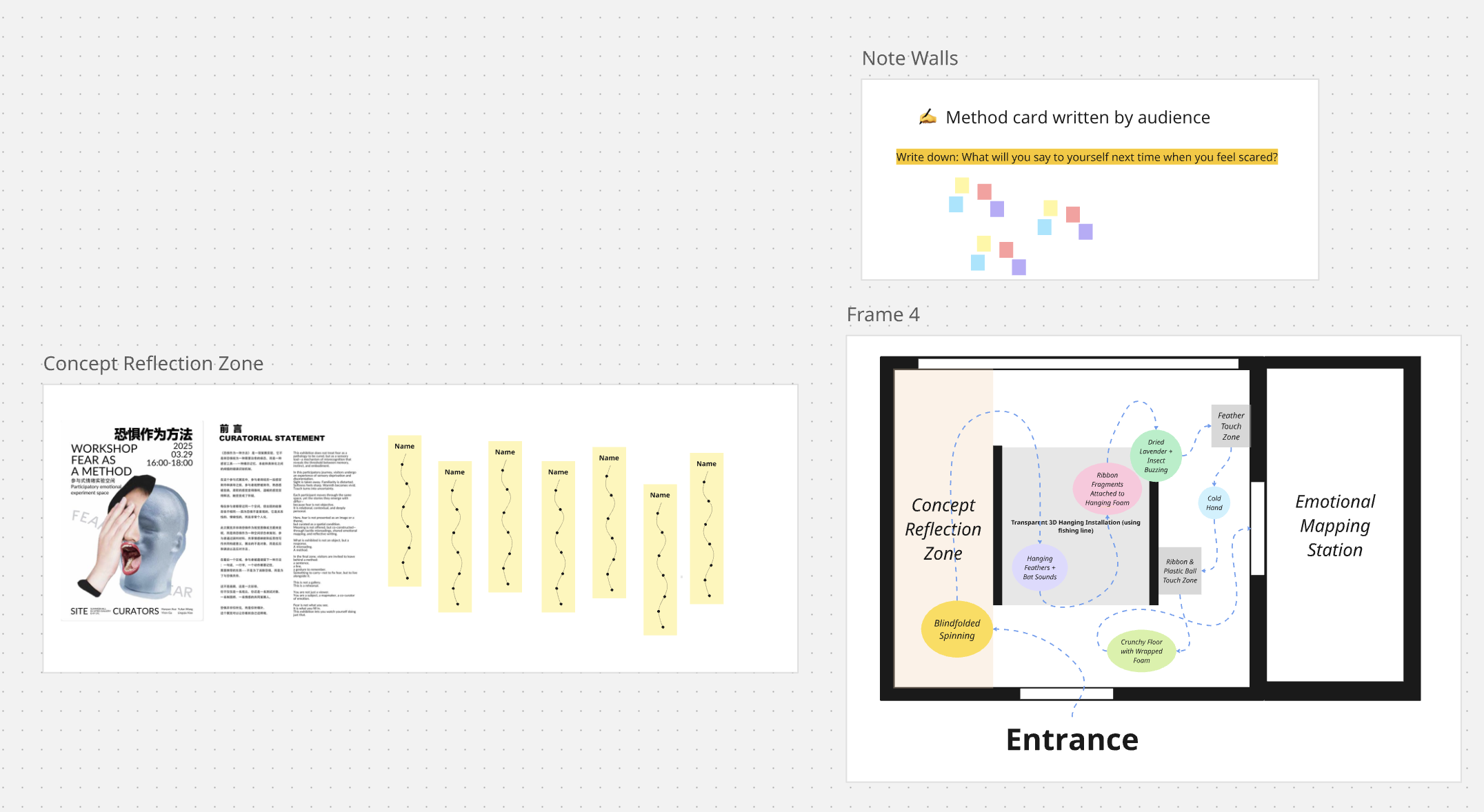

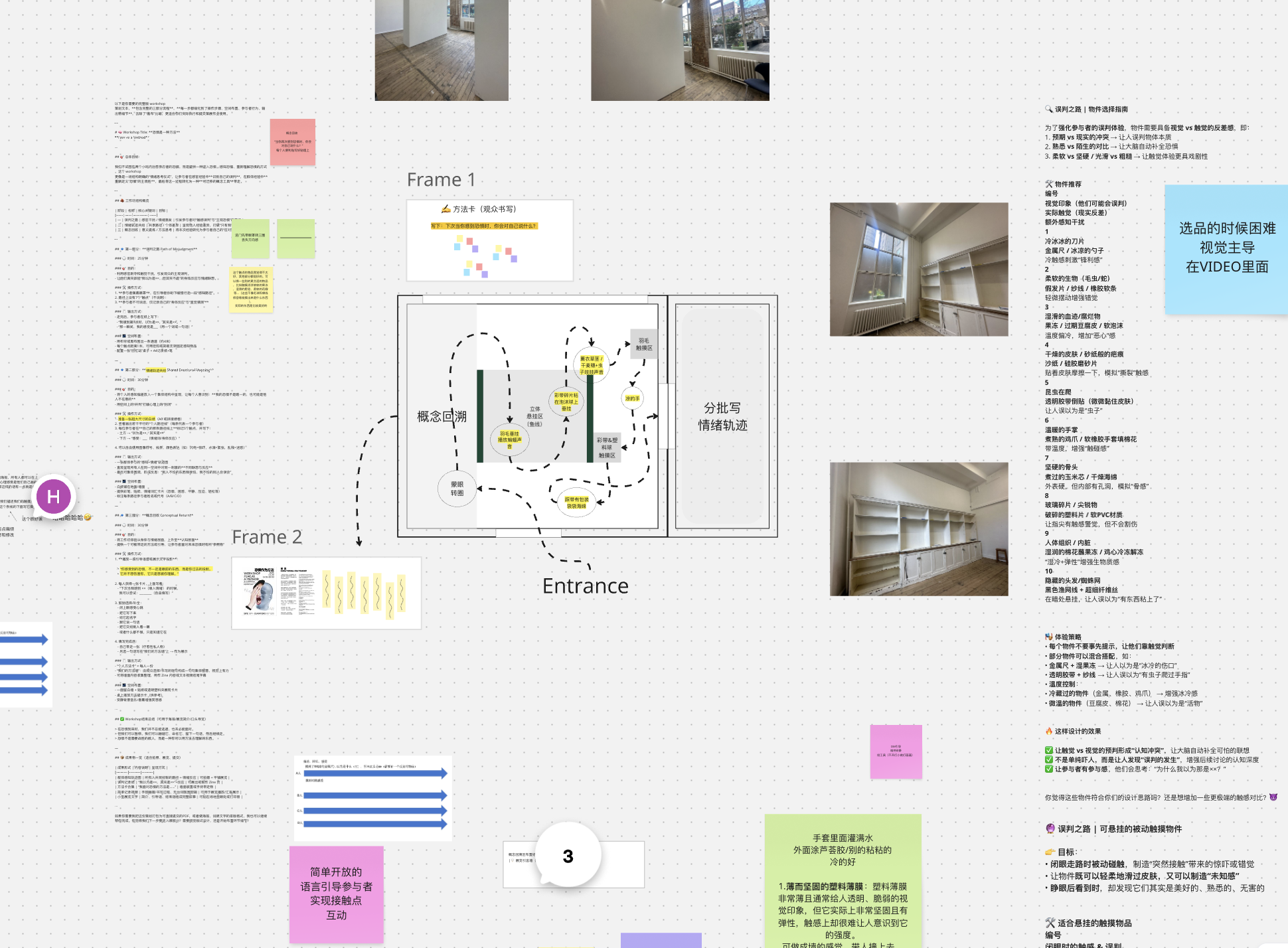

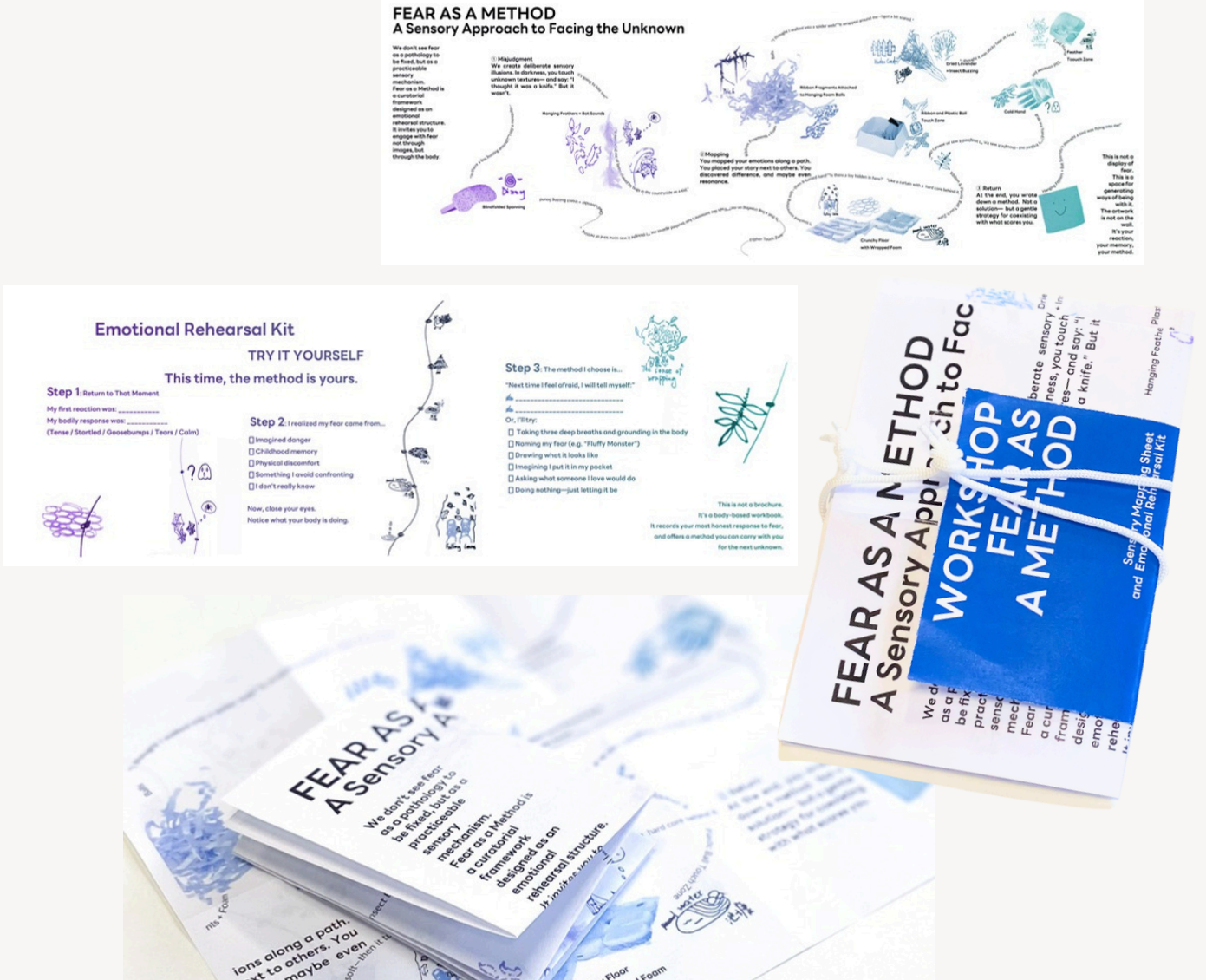

(“Fear as a Method” sensory route – exhibition layout sketch, April 2025. Includes Blindfold Zone, Crunch Floor, Ribbon Installations, Producer of the effect drawing: Yiran Gu.)

W9: Publishing as Curation

This week was perhaps the most transformative for me. We studied “The Phone is the Keyhole; The Penpot, the Heart” and I was completely moved. Their refusal of polish, their embrace of emotional honesty, and their prioritizing of friendship as method helped me see publishing not as post-event documentation, but as an integral part of the curatorial experience.

So I proposed:

“Let’s make the back side of our zine a toolkit.”

“Not just to reflect, but to use. Something they can take away.”

I designed the emotional kit section with fill-in prompts, soft design choices, and handwritten elements—so participants could continue the workshop privately, on their own terms.

(Zine mock-up: Designed and written by the team, All images are co-created by the event participants. )

III. Making and Unmaking: Group Process and Living Diagrams

Our group worked in Miro constantly. Looking back, our board doesn’t just show logistics—it shows our thinking style: layered, nonlinear, highly emotional. We mapped quotes, fears, diagrams, workshop flows, and even doubt. The board became a record of not just what we did, but how we made decisions. This was also the first time I felt fully comfortable disagreeing in a group—I knew my ideas (and feelings) had space.

Together we refined:

- The misjudgment stations (I curated the sound textures).

- The route structure (I directed how the body flows).

- The language tone (I crafted the closing reflection speech).

- The publication design (I created the concept for the emotional takeaway page).

(Miro process map – team discussion and emotional mapping Screenshot from team Miro board, March 2025. Author: Team archive.)

(Miro process map – team discussion and emotional mapping Screenshot from team Miro board, March 2025. Author: Team archive.)

IV. The Workshop: A Rehearsal for Courage

On the day of the workshop, I was nervous. Not about logistics, but about whether people would actually feel something. We weren’t showing art. We were inviting people to surrender their sight, to misjudge, to be vulnerable.

At the end of the route, I delivered the final speech:

Thank you for walking this path.

Maybe you didn’t guess anything right.

Maybe you startled yourself.

Maybe—you weren’t afraid at all.Sometimes, fear isn’t a mistake. It’s a reminder.

It says: “There’s something here that frightens you.”

Maybe it’s a memory.

Maybe it’s something from childhood.In the dark, fear becomes clearer.

But often, fear comes not from what’s real—

but from what we imagine.

Reality is rarely as terrifying as our minds make it out to be.When you realise that what you’re afraid of

is actually a past wound speaking,

and when you gather the courage to face it—

that fear may already be halfway gone.Now, write one sentence—

a message for a future version of yourself who might be afraid.

When fear returns, how will you remind yourself?Remind yourself that we always have courage.

Enough to face one unknown after another.This is the little method you take with you today.

A quiet piece of courage that belongs only to you.

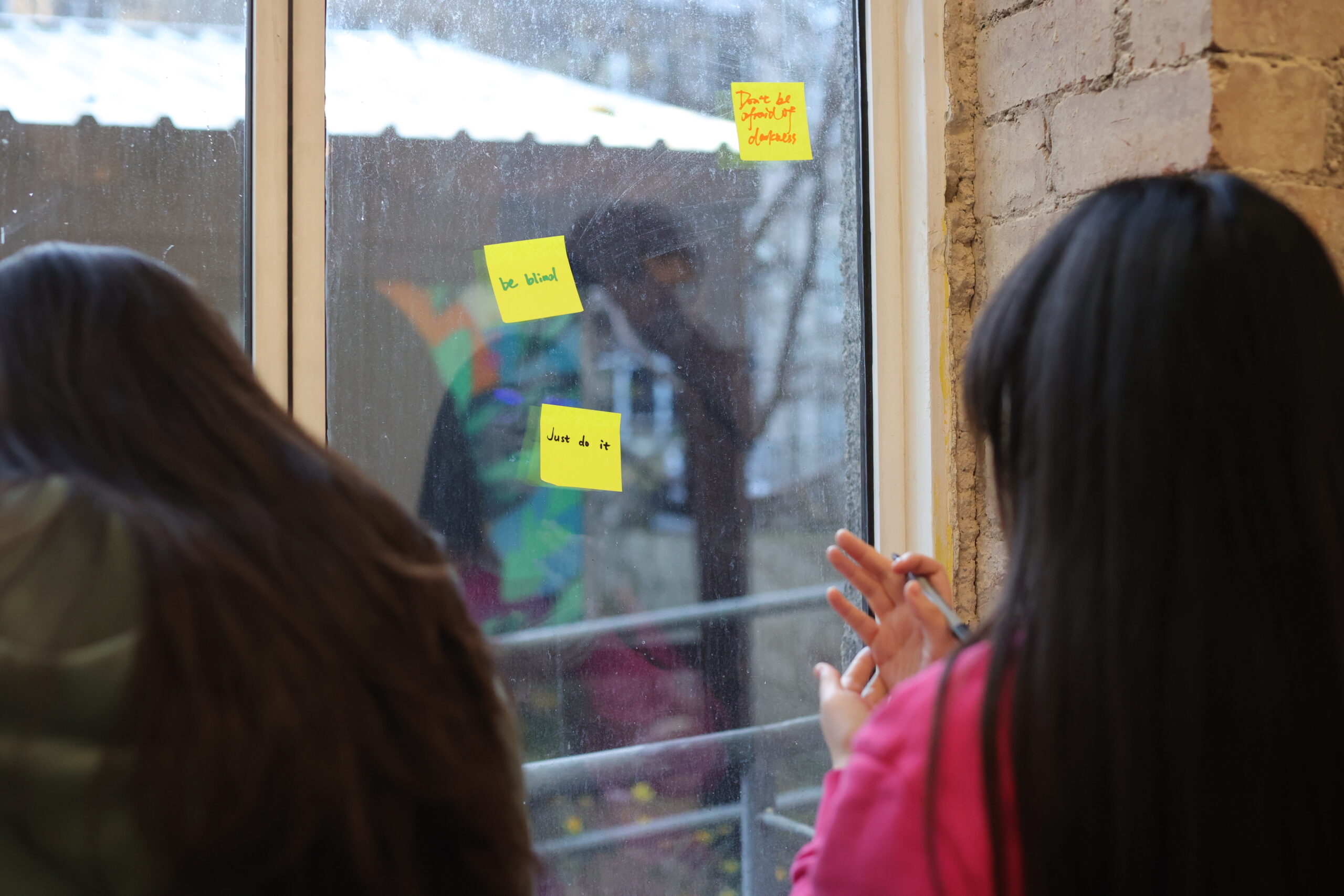

They took the zines. They wrote themselves notes for the future.

And I watched them place those sticky notes on the wall—

each one a small sentence of survival.

V.Team Roles and Contributions

1. Hanyun Xue — Experience Curator (Emotional Facilitator)

As the group’s emotional anchor, Hanyun served as the guide and psychological support throughout the experience. With her background in art and counseling, she shaped the language of comfort and trust. Her voice—calm, attentive, and clear—helped participants navigate their fear safely, especially in moments of sensory disorientation.

2. Lingqiu Xiao — Spatial Choreographer (The Lobby Manager)

As the “lobby manager” of our emotional space, Lingqiu took charge of real-time movement and crowd coordination. Like a stage choreographer, she arranged the physical flow of participants with a sharp eye for timing and calm control. From managing transitions to maintaining safety during blindfolded routes, she held the space with both precision and empathy.

3. Yiran Gu — Sensory Orchestrator (Media & Technical Lead)

Acting as our behind-the-scenes technician, Yiran handled both sound design and video documentation. She composed the atmospheric sound layers and recorded the workshop with sensitivity—capturing fleeting gestures, silences, and reactions. Her work preserved the ephemeral feeling of the event and helped us build a self-archive rooted in emotion.

4. Yufan Wang — Service Narrator (Flow & Discipline Coordinator)

Taking on the role of “discipline coordinator,” Yufan made sure everything ran smoothly. She oversaw timing, participant rhythm, and station transitions. Quiet but ever-present, she was the backstage voice who ensured that nothing felt rushed or chaotic. Her sense of order gave structure to the experience—and her steady presence made it feel secure.

My Role, My Reflection

| Task | Description |

|---|---|

| Theme Initiation | Proposed the core concept “Fear as a Method” during the first brainstorming session. |

| Sound Design | Selected and edited sound textures for sensory misjudgment zones (e.g. insects, feathers). |

| Route Planning | Designed the blindfolded walking route; guided spatial pacing and emotional rhythm. |

| Emotional Toolkit Design (Zine) | Created the reflective back page of the zine with writing prompts and coping actions. |

| Closing Speech | Wrote and delivered the final speech during the workshop to reflect on emotional insights. |

| Exhibition Recap (PPT) | Co-developed the final presentation slides on team roles, outcomes, and reflections. |

1: Research

We applied emotional ethics (W4), sensory curation (W6), and affective publishing (W9) directly into the design of this project. We referenced not only course texts but practices by artists like Marina Abramović (who uses presence as method), and Tramway’s Jarman exhibition (W7), which made private pain public without aestheticizing it.

2: Practice

I coordinated theme direction, sensory station design, wrote and delivered the workshop’s closing, and authored the emotional reflection page in the zine. I also curated sound elements, choreographed the route, and contributed to visual consistency in our publishing and video documentation.

3: Reflection

I realised that curating isn’t about “creating something to be looked at.” It’s about creating a space where something can happen—for real people, in real time. The workshop was about trust. And we earned it.

VI. Outcomes Are Not Just Outputs

Our project ultimately consisted of four interwoven outcomes:

-

The exhibition route: a designed walk of fear, confusion, and intimacy.

-

The zine: an object that lives beyond the space, with both theory and practice.

-

A short documentary video, capturing both audience reactions and our own reflections.

(Still from “Fear as a Method” video documentation Video produced by our team, filmed during final workshop day at summerhall. Screenshot: April 2025.)

-

Our curatorial presentation (PPT), which archived our judgment, not just our actions.

Looking Back, and Forward

Fear as a Method was not perfect—but it was personal, alive, and full of care. We didn’t aim to heal people. We offered them a method to rehearse feeling, misjudgment, and return.

It taught me what kind of curator I want to be:

Not a guide. Not a gatekeeper.

But a quiet facilitator of difficult feeling.

That, to me, is where curating begins.

![Home [www.victoriesnautism.com]](https://th.bing.com/th/id/R.b8f4afd386a99f83da117cdc1585f9ed?rik=NFwJMjNv3U0pLw&riu=http%3a%2f%2fwww.victoriesnautism.com%2fuploads%2f4%2f0%2f4%2f0%2f4040527%2f9118470_orig.png&ehk=vzG%2bDm1Bh231I9%2flBWhKI2EQ77dMYvfxNX%2bAa7s1IoY%3d&risl=&pid=ImgRaw&r=0)

Why she fits: Keyi’s use of spatial perception echoes Aneta Szyłak’s theory of “curating context” (The Curatorial, 2013), where space and sensation are integral to meaning.

Why she fits: Keyi’s use of spatial perception echoes Aneta Szyłak’s theory of “curating context” (The Curatorial, 2013), where space and sensation are integral to meaning.