The Exhibition as a System, Not a Site

If traditional exhibitions lead the audience along a prescribed path, my curatorial model throws out the map.

When I first walked into the ECA Main Building Lobby, it felt like an in-between space—a transitory zone of coffee, conversation, passing glances. But in that looseness, I saw possibility: an open matrix for curatorial action. This wasn’t a white cube; it was a commons. A site already filled with movement, energy, and student voices. And that mattered, because decentralised curating isn’t just about who speaks—it’s about where voices collide.

Choosing this space was a pivot moment. I moved from abstract ideas of online platforms and speculative architecture (like my earlier imagined version at FACT Liverpool), to something grounded, temporal, and alive. The lobby would host a rewritable exhibition, one that changes form, shape, and meaning through constant interaction.

Fluidity in Physical Form: Rhizomatic Design

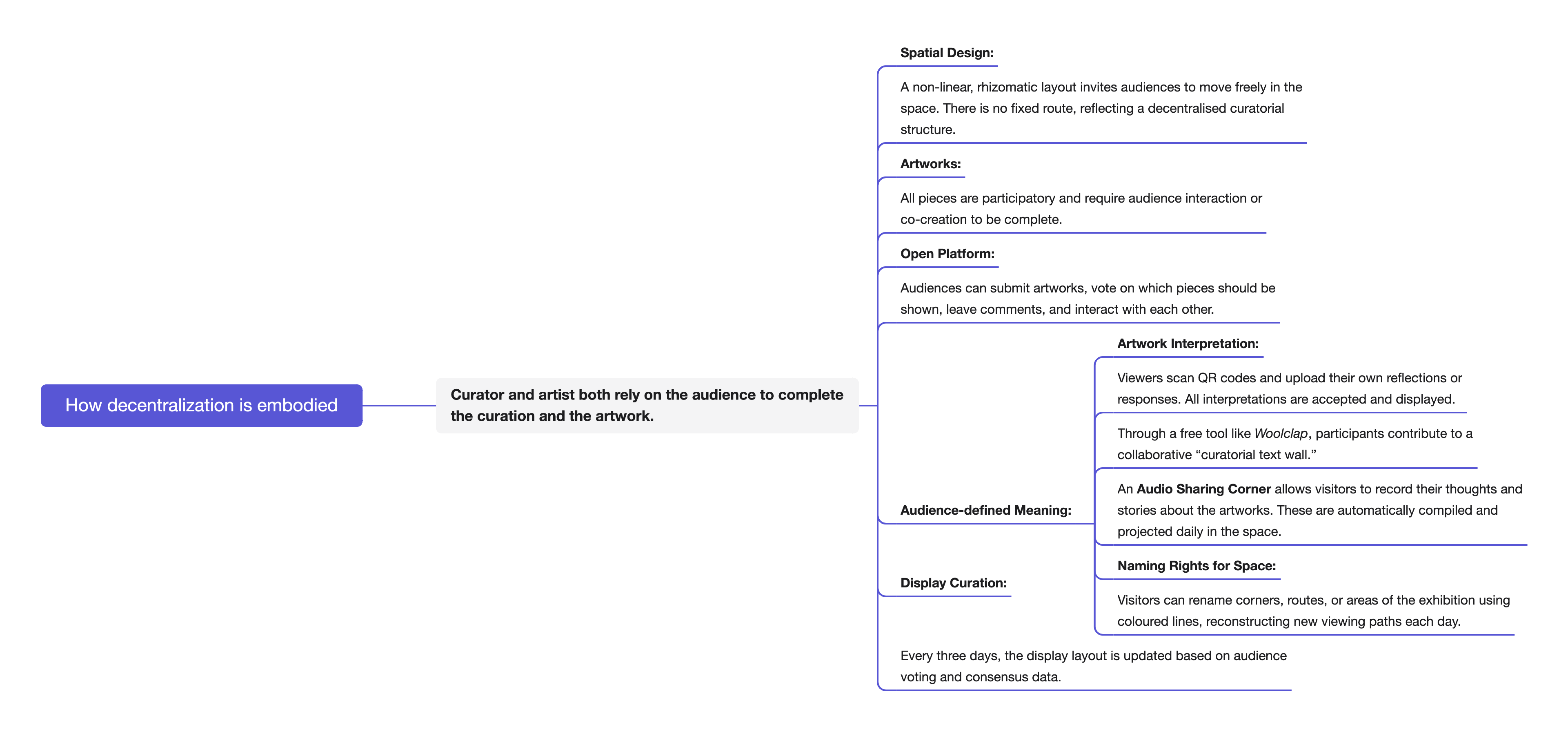

Traditional exhibitions follow a path: entrance, sequence, exit. But Fluid Curating is built differently. I wanted to resist linearity and build an environment that feels more like a network—messy, rhizomatic, open-ended.

So I designed a spatial system where the layout is responsive, where visitors shape not only what they see but how they move.

Inspired by Utopia Station (Venice Biennale, 2003), I began thinking of the exhibition not as a container but as a field: polyvocal, unscripted, soft-edged. The layout of Fluid Curating reflects this. Colour-coded tapes allow visitors to map their own trails. Corners become naming zones. A sound corner becomes a communal listening post.

Using low-cost signage, mirrors, floor text, and Woolclap-enabled QR codes, visitors can name spaces, remix routes, and co-author interpretations. The space becomes a map in motion.

Rather than fix meaning in place, this design allows it to shift with presence. Every three days, a soft rehang is conducted based on audience interaction data, comments, and collective votes. This ensures the exhibition evolves not just structurally but conceptually—staying fluid, alive.

Below is a selection of images from the exhibition Utopia Station (Venice Biennale 2003), showing typical features of its “rhizomatic exhibition layout”

Rather than assigning movement, I invite navigation. This aligns with ideas explored in Week 7 (Site Visit) and Week 8 (Systems Curation): space isn’t a backdrop, it’s a co-author.

Rather than assigning movement, I invite navigation. This aligns with ideas explored in Week 7 (Site Visit) and Week 8 (Systems Curation): space isn’t a backdrop, it’s a co-author.

System as Sensory Engine: What Visitors Touch, Say, Change

Visitors activate:

- A sound-sharing corner to record voice reflections (Woolclap-based)

- A co-curation wall that projects daily audience annotations

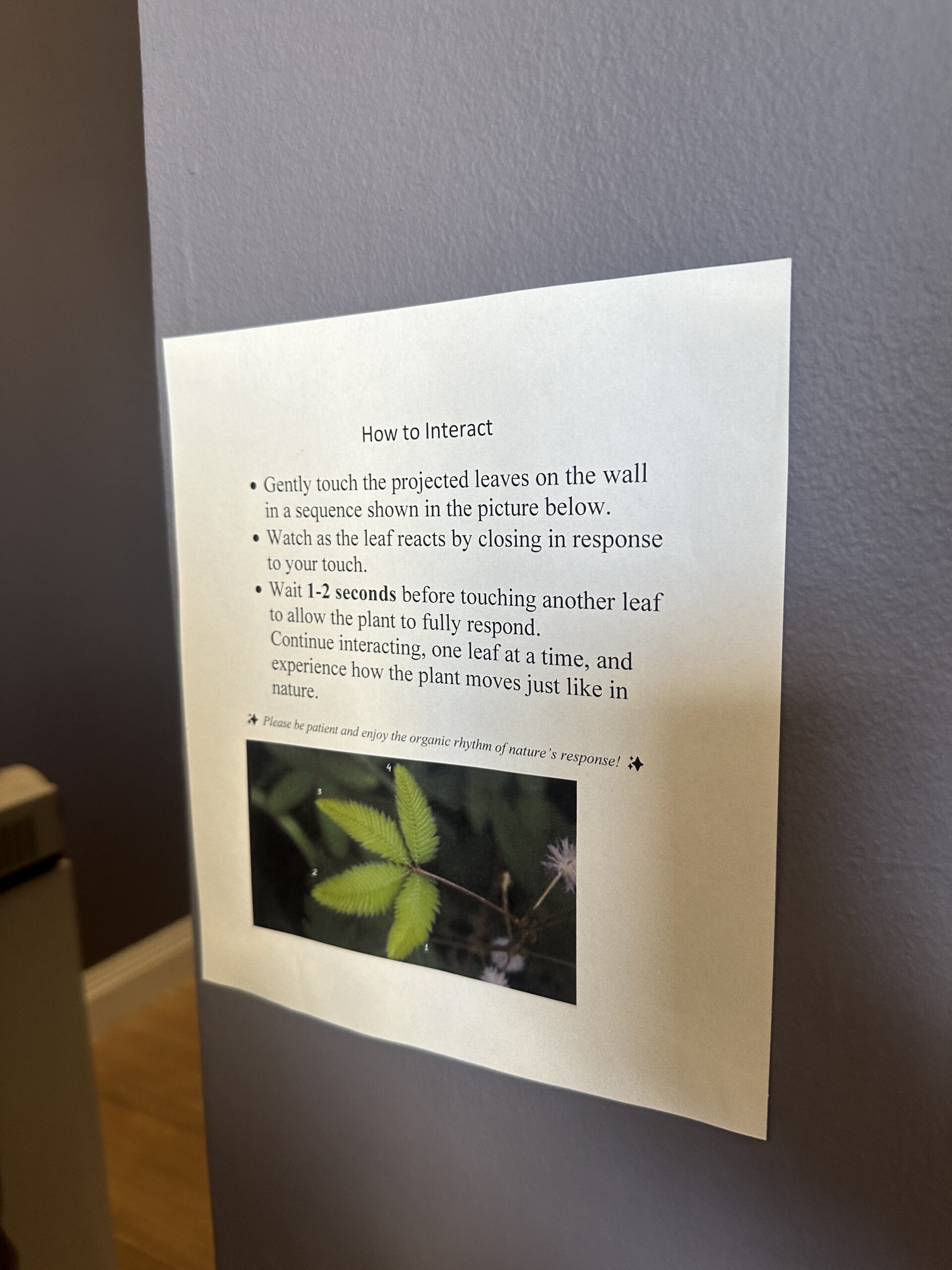

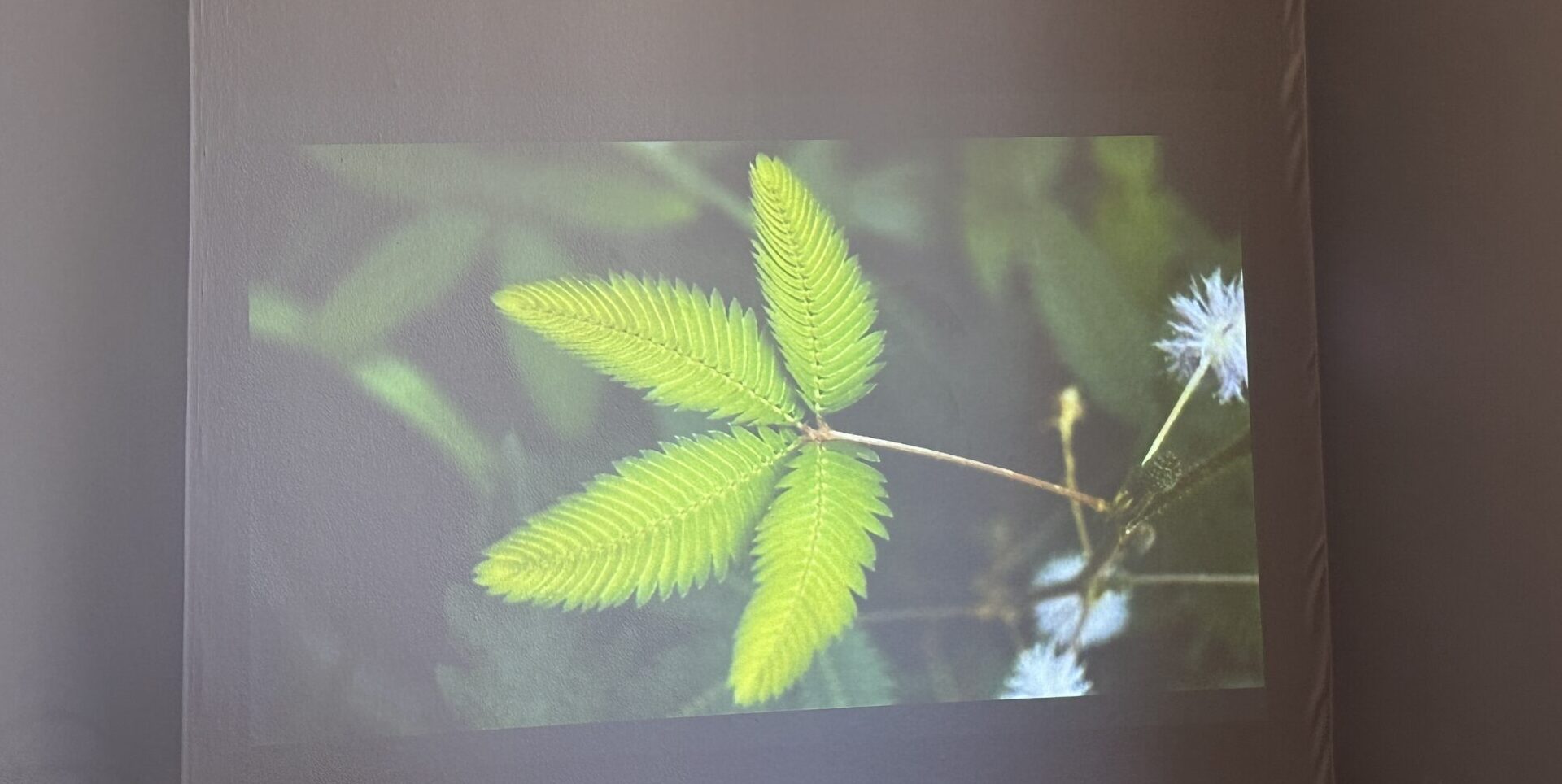

- A motion-tracked zone where artworks respond to proximity

These elements are low-tech but high-agency. They embody Rudolf Frieling’s assertion in The Art of Participation (2008) that interactivity isn’t a feature—it’s a political design choice.

The Lobby as a Living Platform: Why This Space Works

The ECA lobby already has precedent: previous CAP pop-ups and student shows. It is accessible, non-intimidating, and constantly used. I didn’t need to manufacture a public—I needed to listen to the one already there. This learning came from Week 7, where we were encouraged to consider affective and temporal qualities of space.

What I changed: I dropped the screen-heavy modular setup. I replaced complex algorithms with analogue trails. I learned that if I wanted people to leave a trace, I had to leave room for them to enter.

Cross-School as Co-Structure: Institutionalising Decentralisation

But decentralisation isn’t only about audience freedom—it’s also about institutional permeability.

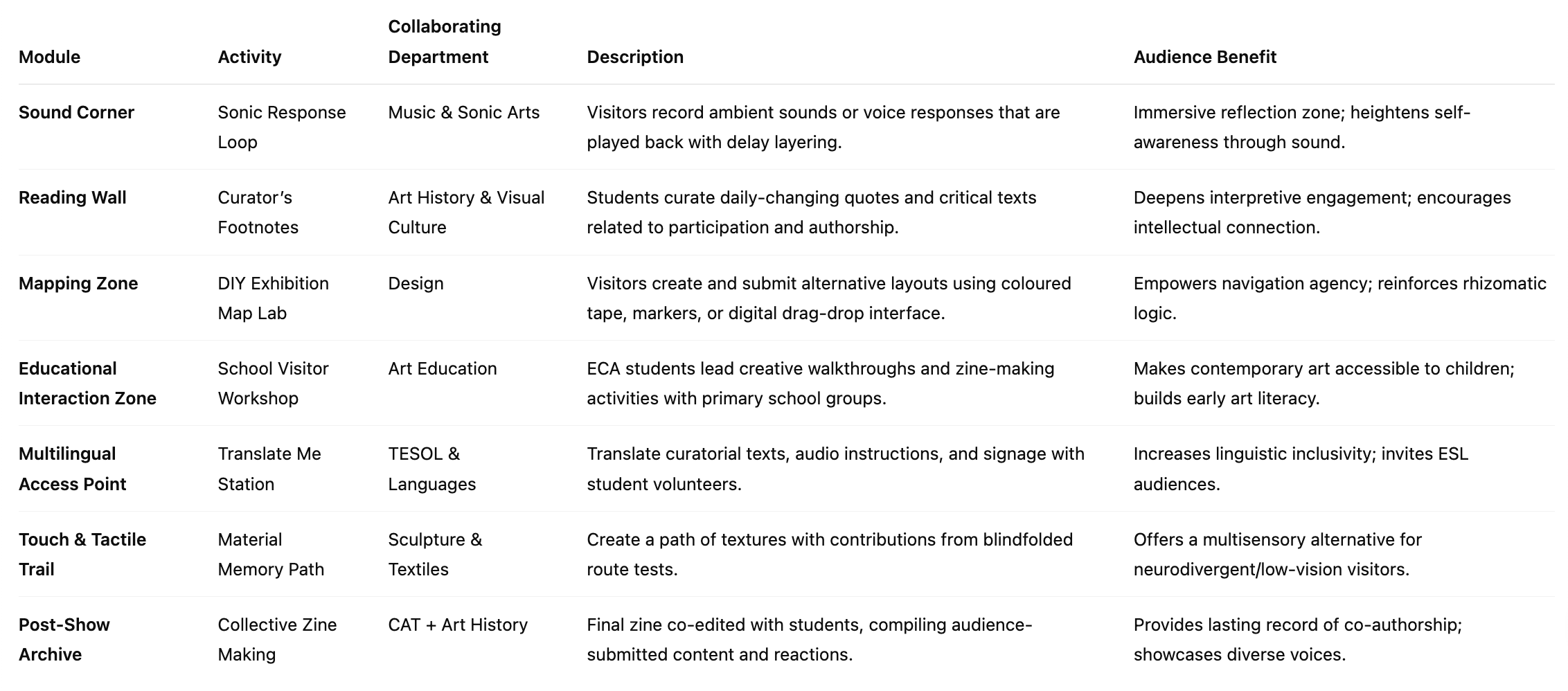

That’s why Fluid Curating integrates a “Cross-ECA Co-Curation Strategy.” Rather than curating in isolation, I’ve invited students and staff across disciplines to build the infrastructure with me:

This idea inspired by Week 8’s emphasis on systems thinking and Week 9’s discussion of publishing as a collaborative act, I asked myself:

What if curating became a campus-wide conversation?

🛠️ Preparation Process: Step-by-Step

1. Observing institutional blind spots

While reviewing feedback from CAP students, I noticed that many of them, especially those working with participatory media, struggled to collect consistent audience responses. At the same time, my own curatorial proposal faced challenges: limited tech budget, the need for inclusive accessibility, and the pressure to show peer collaboration. That’s when it clicked—what if my exhibition could help solve their problems, while they solved mine?

2. Mapping the school’s potential collaborators

I began by mapping existing departments and MA programs across ECA and identifying their practical strengths:

Music & Sonic Arts for spatial audio design

Art History & Visual Culture for exhibition annotation

Design for participatory mapping and signage

TESOL and Inclusive Education for multilingual accessibility

Art Education for school-focused workshop delivery

CAT and Art History again for Zine editing and curatorial discourse

This wasn’t about token inclusion. It was about building functional, mutual dependencies—where each group contributed something they were already practicing, but within a new curatorial framework.

3. Designing co-owned modules

Rather than just inviting contributors after the fact, I restructured my Programme Notes to create built-in modules of collaboration:

A Sound Corner with music students composing daily responses

A Reading Wall curated by art historians

A DIY Map Lab developed by designers

A Multilingual Access Point for TESOL students to prototype language supports

A Zine station for CAT peers to help me rethink curatorial authorship

Each of these became more than exhibition features—they were opportunities for knowledge-sharing and horizontal authorship.

(Cross-ECA Co-Curation Strategy: Activity Table)

4. Framing the collaboration as part of the exhibition’s logic

To maintain coherence, I ensured each collaborative element aligned with my curatorial ethics: fluidity, co-authorship, and responsiveness. That meant:

Avoiding fixed panels—replacing them with writable, reconfigurable surfaces

Offering open tools for annotation, rather than locked-down text

Visualising visitor contributions and collaborators’ inputs with equal weight

This process taught me that decentralised curation isn’t about removing structure—it’s about multiplying access points. By integrating cross-school collaboration into the curatorial core, Fluid Curating doesn’t stretch beyond itself—it stretches into relevance.

Each department I invited didn’t dilute the vision; they deepened it. They helped the project breathe through different vocabularies, senses, and pedagogies.

In doing so, the exhibition becomes more than a showcase—it becomes an organism co-constructed by the rhythms of a knowledge community.

🌊 My Exhibition Is Not a “Finished Product,” But a Flowing Relationship

🌊 My Exhibition Is Not a “Finished Product,” But a Flowing Relationship

Peer Review: Chuyue Xu’s Curatorial Project “Female Narratives in Opera: History and Liberation”

Peer Review: Chuyue Xu’s Curatorial Project “Female Narratives in Opera: History and Liberation”

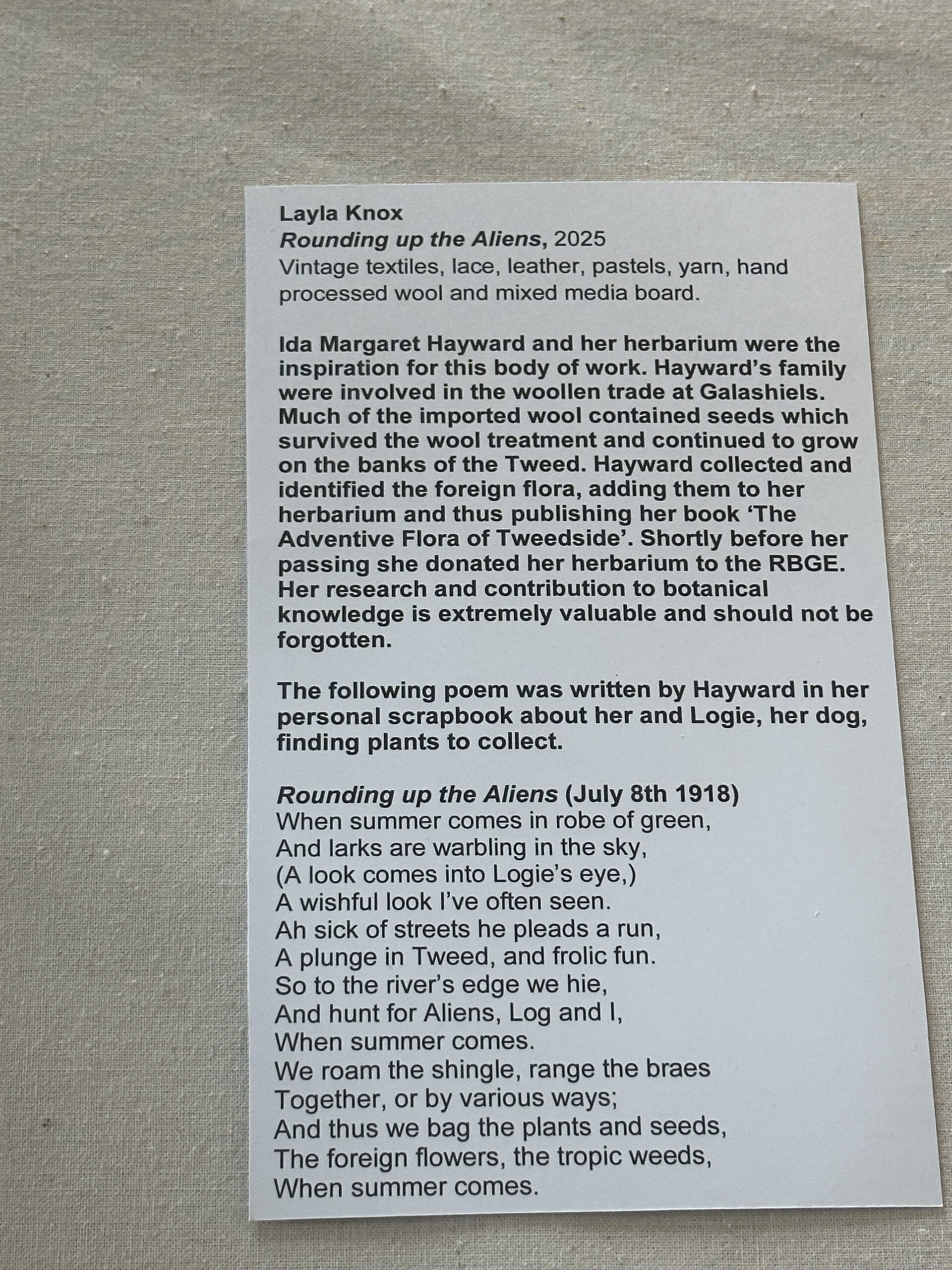

This week, I visited CORPSE FLOWER, an exhibition curated by MA Contemporary Art Practice students at Inverleith House, Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh. The show examined the delicate balance between fragility and resilience in plant ecosystems, mirroring the fleeting bloom of the Titan Arum (the “Corpse Flower”)—which flowers for just a day before decaying. 🌺💫

This week, I visited CORPSE FLOWER, an exhibition curated by MA Contemporary Art Practice students at Inverleith House, Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh. The show examined the delicate balance between fragility and resilience in plant ecosystems, mirroring the fleeting bloom of the Titan Arum (the “Corpse Flower”)—which flowers for just a day before decaying. 🌺💫