Reflective Blog: Rethinking “Fluid Curating” – From Conceptual Ambition to Grounded Possibility

Reflective Blog: Rethinking “Fluid Curating” – From Conceptual Ambition to Grounded Possibility

1. Initial Vision: A Decentralized, Tech-Driven Exhibition

When I first began shaping the idea for Fluid Curating, my ambition was to create a dynamic, audience-led exhibition model that fully embraced decentralization—where curatorial authority would no longer rest solely with the curator but be shared with artists, audiences, and market forces.

I was drawn to terms like “NFT,” “blockchain,” and “Web3,” which seemed to promise transparency, open participation, and algorithmic co-curation.

Inspired by digital culture and new media trends, I envisioned a hybrid exhibition across a physical site and online platform, with real-time artwork reconfiguration based on audience voting and NFT market trends.

2. Critical Feedback and Conceptual Challenges

However, during peer review and my tutorial feedback, I was faced with key challenges that pushed me to rethink this plan.

One major issue was the conceptual clarity of some core elements. My peer reviewer, Yuhang Yang, questioned how terms like NFT and blockchain—actually supported the idea of a “fluid” or time-sensitive curatorial logic. As I reflected on this, I began to see the contradiction: while my project sought to highlight ephemerality, transformation, and flux, NFTs, by their very nature, are mechanisms for permanence, ownership, and archival preservation. Their association with speculative market value also risked reducing curatorial decision-making to financial metrics, which ran counter to the community-led values I wanted to embrace.

Another question raised during feedback was: What tool or system could actually support this curatorial complexity in practice? I realized my original plan combined too many advanced technologies and open-ended processes without clearly demonstrating how they would function together. As a result, the exhibition risked becoming fragmented—more of a conceptual collage than a coherent experience.

Beyond conceptual concerns, there were also practical limitations. My initial choice of venue—FACT Liverpool—was exciting but ultimately unrealistic. The projected budget far exceeded the £2000 limit.

The technical demands, duration, and uncertainty of long-term online platform maintenance added more instability.

These challenges didn’t discourage me—instead, they became catalysts for productive rethinking.

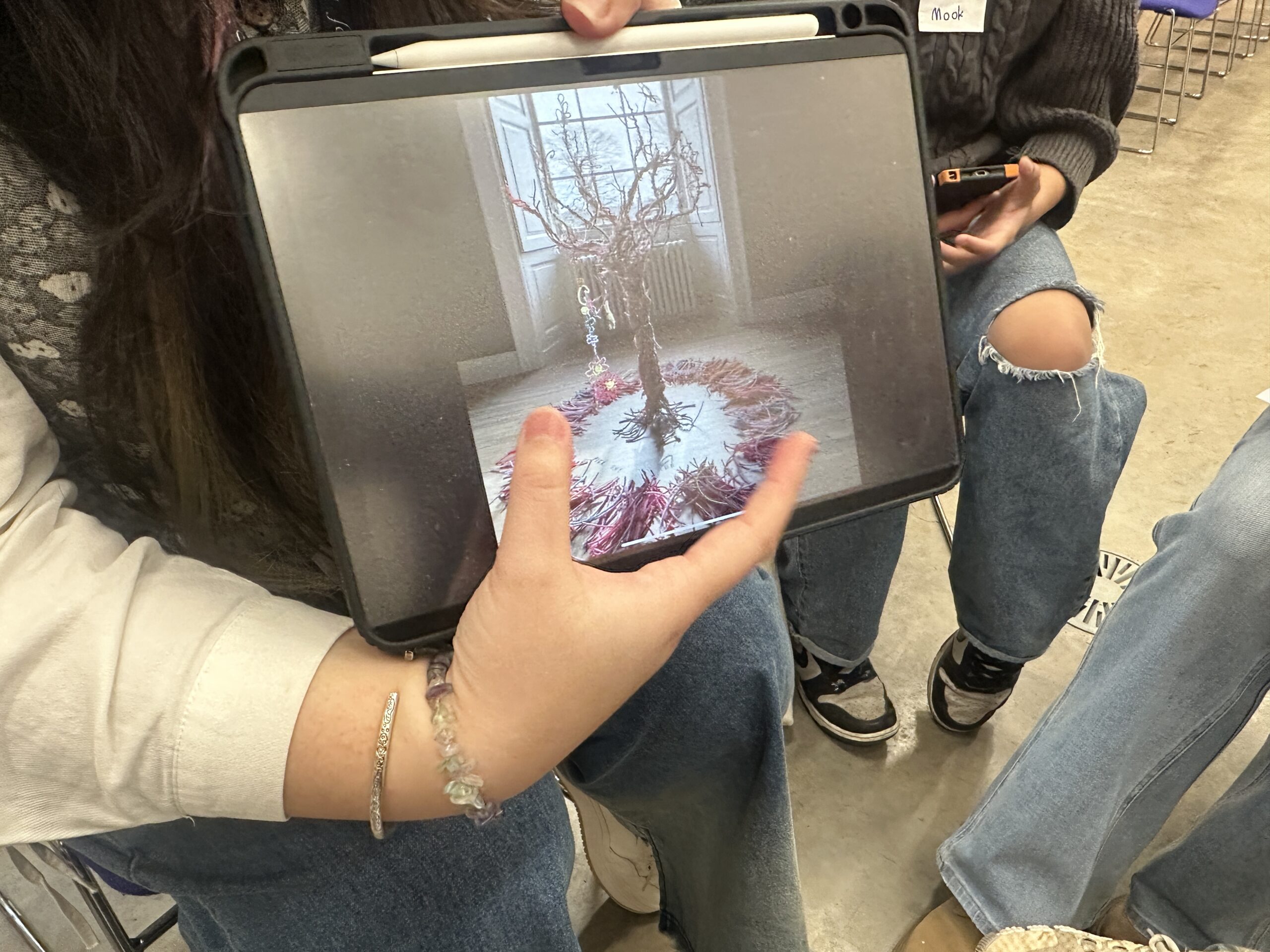

3. Turning Point: Visiting Participatory Works by CAP Students

A defining moment in my curatorial journey came during a joint event between CAT (Contemporary Art Theory) and CAP (Contemporary Art Practice) students.

blog link:

This experience moved me deeply. I was struck by the raw potential of these young artists, their vulnerability, and their innovative use of participation. Many works relied on interaction—audiences speaking, touching, or altering the piece to complete it.

And suddenly, something clicked.

I had spent so much time trying to simulate “fluidity” through technology—imagining algorithmically shifting displays, blockchain-backed value systems, ever-changing screen layouts.

I thought decentralisation meant sophisticated mechanisms: rapid visual updates, complex voting platforms, market-responsive curation. But here, right in front of me, were works that already embodied decentralisation, through something more organic: Audience participation.

These artworks didn’t need flashy screens or AI sensors. What they needed was space—for the audience to step in, to shape meaning, to complete the work.

I realised that the artists and I had been walking parallel paths—both seeking to blur authorship, to soften control, to share decision-making. In that moment, I saw myself not as a controller of space, but as a facilitator of resonance. My curatorial voice didn’t have to dominate; it could listen, invite, and hold.

This was the real turning point. I let go of the need for tech-heavy infrastructure and embraced a more grounded, people-centered approach.

4. Rethinking Participation: From Tech to Human Presence

Around the same time, I was writing peer feedback for Xuchuyue’s curatorial project. She used opera not just as a theme, but as a structural framework—with rhythm, tension, and release shaping the audience’s emotional journey.

Her approach made me question my own assumptions. I had believed audience engagement needed to be mediated through technology. But her project reminded me: participation can begin with something far simpler. Inviting someone into another’s story, another’s voice, can be a powerful act of decentralization.

I began asking myself: Where does emotion happen in my exhibition? Have I left enough space for people to feel, not just interact?

What I’ve Learned

This journey has taught me that decentralization in curating isn’t just a structural or technological shift—it’s a relational practice. It means inviting people in, letting go of control, and designing with sensitivity to affect, ethics, and community.

Reading and responding to Xuchuyue’s work opened my eyes to emotional architecture. Visiting the CAP studios showed me the strength of collaboration over spectacle. And listening to feedback forced me to ask hard but important questions.

In the end, Fluid Curating is no longer a conceptual ambition suspended in technical abstraction. It is now a practice grounded in people, space, and story—one that breathes, listens, and changes with those who participate.