The quotes in the foreword and epilogue are originally from Boyi Feng's account of the exhibition "Domino Plan in the Space" he curated in 2009, which has been recorded in his book I'm with the Future Ahead: Boyi Feng's Curatorial Stories (2024).

WEEK13|Individual Curatorial Projects

WEEK12| Draft Individual Project Proposal

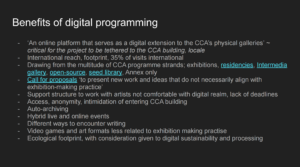

WEEK11|How digital curation is redefining the art experience

In the field of contemporary art, digital curation not only challenges the traditional curatorial model but also opens up new ways of artistic expression and audience engagement. By attending Alex Misick’s fascinating presentation, I returned to my personal project Echoes in Blue: A Dialogue Across Generations, which aims to present the traditional art of blueprints through a digital platform to promote cross-generational cultural transmission and global dialogue.

The Transformative Power of Digital Curating

Digital curation has brought about fundamental changes in the way audiences engage with art exhibitions by extending their reach and interactivity (Misick, 2024). According to Gere (2002), digital technologies can break through the limitations of physical space and provide a richer art experience, and Parry (2010) has suggested that digital platforms can effectively support cross-cultural dialogue and the global dissemination of art. In the Echoes in Blue project, I am particularly interested in how augmented reality (AR) can be used to illustrate the production process and cultural stories of blueprint fabrics, allowing the audience to experience the details of the crafts in a visually intimate way (Bolter et al., 2006).

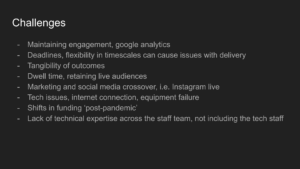

Misick, A. (2024) Digital Curation at CCA. [PPT] Presented at CCA.

Technological Challenges and Reflections

While digital technologies such as AR and VR have brought new means of display to art exhibitions, they also pose the challenge of maintaining audience engagement without sacrificing the physical sensory experience of the artwork. Locher and Dolese’s research suggests that an over-reliance on technology may diminish the physical perceptual qualities of the artwork. In response to this issue, I have designed the Echoes in Blue exhibition with a deliberate hybrid curatorial approach that aims to preserve the tactile and textural qualities of blueprint fabrics through a combination of physical displays and digital interactions, whilst utilizing digital tools to increase educational and interactive qualities. This strategy aims to overcome the limitations of traditional and modern display technologies to ensure that the sensory quality of the artworks and audience engagement can be balanced (Locher & Dolese, 2004). In addition, the use of virtual reality (VR) technology can provide audiences with an immersive art experience that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the cultural and historical context of the artwork (Kluszczynski, 2010).

Misick, A. (2024) Digital Curation at CCA. [PPT] Presented at CCA.

Integrating Digital Tools in Practice

Referring to Misick’s account of the CCA Annex project, I realized that mixed reality and virtual reality technologies can effectively bridge the gap between traditional art and modern audiences. According to Wahid et al.’s (2021) systematic literature review, they explored in detail how digital tools can be used to preserve and promote intangible cultural heritage in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This research is instructive on how I can use digital technologies to promote the art of blueprints globally, specifically providing theoretical support on how these tools can be utilized to strengthen the cultural identity and understanding of the audience. The integration of AR and VR technologies has enabled audiences from different cultural backgrounds to understand and appreciate the cultural and historical dimensions of this traditional craft (Wahed, Saad, & Yusoff, 2021).

Future Directions

The CCA workshop enhanced my understanding of the potential of digital curation and strengthened my commitment to applying these technologies to my own curatorial projects. Through theoretical research and practical exploration, I am committed to making the Echoes in Blue project a showcase for the intersection of culture and technology.

Constructive responses to group projects

In the Domino Project group project, after two offline discussions, we also plan to adopt digital curatorial tools, Grau (2004) explored in detail how digital technology can transform artistic expression and audience experience, pointing out that virtual art is able to deepen the audience’s understanding and perception of artworks through the creation of immersive experiences. Our project plan uses the Instagram platform to create the #DominoProject hashtag to synchronise the exhibition, creating digital or virtual components that can be accessed remotely breaking down physical and spatial constraints to provide a continuous art experience for a global audience.

This curatorial practice not only demonstrates the dynamic nature of contemporary art, but also reflects how digital platforms make connectivity between individual exhibitions possible.

References

Misick, A. (2024). Digital Curation at CCA: Challenges and Innovations. [Lecture notes]. Retrieved from CCA.

Parry, R. (2010) Museums in a digital age. London: Routledge.

Locher, P. & Dolese, M. (2004) A Comparison of the Perceived Pictorial and Aesthetic Qualities of Original Paintings and Their Postcard Images. Empirical studies of the arts. [Online] 22 (2), 129–142.

Kluszczynski, R. (2010) Strategies of interactive art. Journal of aesthetics & culture. [Online] 2 (1), 5525-.

Gere, C. (2002). Digital Culture. London: Reaktion Books.

Bolter, J. D. et al. (2006) Windows and mirrors: interaction design, digital art and the myth of transparency. Information, communication, and society 9 (1) p.125–126.

Wahed, W. J. E. et al. (2021) “Please stay, don’t leave!”: A systematic literature review of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage in the fourth industrial revolution. Pertanika journal of social science & humanities. [Online] 29 (3), 1723–1744.

WEEK 10|Challenges and opportunities for public participation

New Challenges in Contemporary Curating

In “Curatorial Counter-Rhetorics and the Educational Turn” (Wilson, 2010) and “Expanding the Gallery ” (Franks, 2021), curation is positioned as an active social intervention. However, actual case studies reveal that despite the intention of public projects to promote broad participation, their practice often fails to reach the intended diverse audiences. In particular, the use of technology in exhibitions is often assumed to be a means of increasing interactivity, but improper maintenance and over-reliance on technology may instead hinder a deep dialogue between art and the public.

Curatorial Challenges and Theoretical Analysis of Public Projects

Dewey’s (2005) concept of art as lived experience provides me with clues. He argued that art should be integrated into the public’s daily life, not as an elegant pursuit far from life. After the class, I examined public programs on platforms such as FACT. I found that although these projects have made progress in promoting community engagement and arts education, they also face challenges in terms of funding, resource constraints, and measuring social impact. This led me to think back to Relational Aesthetics (Bourriaud, 2002) and Artificial Hells (Bishop, 2012), which suggest how art and curation should be more effectively linked to the arts. curation should interact more effectively with society. For example, the desire to democratize art and make it accessible is noble but often fails in execution that truly transcends the art’s familiarity with the population, and Wilson and O’Neill (2010) point out that the shift in the curatorial field towards education and public engagement must go beyond rhetoric and manifest itself in genuine dialogue and participation. However, as observed in the public programs mentioned, there is still a gap between intention and impact, which is often compromised by logistical negligence or lack of critical reflection on the part of the institution.

Pilvi Takala, Close Watch (2022). Installation view at FACT Liverpool. Photography by Rob Battersby

Melanie Crean, A Machine to Unmake You (M2UY) (2019-2024). Installation view at FACT Liverpool. Photography by Rob Battersby

FACT. (n.d.) Donate [Screenshot]. Available at: https://www.fact.co.uk/donate

Personal Reflections: Redefining the Social Responsibility of Curating

I believe that the social responsibility of curating should be to promote the public’s deeper understanding of art, stimulate critical thinking, and contribute to the cultural and educational development of society. This proves that the technology of curatorial displays must at the same time serve as a bridge between art and the public.

By designing more inclusive and participatory public art programs, curators can create richer art experiences for audiences from different backgrounds. Consider the South London Gallery’s public program and how it uses this platform to deepen the connection between art and the community, tapping into and reflecting the unique culture and needs of the community; and how the NewBridge project explores urban regeneration and social change through art practice. These questions require in-depth reflection and creative solutions from me.

The NewBridge Project. (n.d.) What’s On [Screenshot]. Available at: https://thenewbridgeproject.com/whats-on/

References:

Bourriaud, Nicolas. (2002) Relational aesthetics / Nicolas Bourriaud ; translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods with the participation of Mathieu Copeland. Dijon: Les Presses du réel.

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial hells : participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. 1st edition. London: Verso.

Dewey, J. (2005) Art As Experience. 1st edition. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Wilson, M. & O’neill, P. (2010) Curatorial counter-rhetorics and the educational turn. Journal of visual art practice. [Online] 9 (2), 177–193.

Franks, A. (2021) “Expanding the gallery: Curation, pedagogy and social action in community-based arts programmes,” in Debates in Art and Design Education. 2nd edition [Online]. Routledge. pp. 196–210.

WEEK10|My Peer Review of Zehui Ren’s Blog

Peer review

After reviewing your entire blog content, I found some room for improvement in the key areas of structure and clarity, depth of content, visual presentation, and rigor and citation.

Structure and clarity

Your visit to the Talbot Rice Gallery in Week 3 shows a depth of insight, but the overall structure is disorganized. I recommend you to refine the structure, e.g. by dividing Week 3 into sections such as ‘Art Appreciation’ and ‘Curator Interviews’, which are clearly distinguished by subheadings. In addition, the content is a little light on linking individual experiences to wider art theory and contemporary curatorial practice. Acord (2010) refers to the role of the curator in the production of artistic meaning, demonstrating how curatorial knowledge and plans are elaborated and modified through the specific actions of the exhibition installation; Bourriaud, N. (2002) and Bishop, C. (2012), discuss the role of the curator in the production of artistic meanings. (2012), also discusses participatory theories of art, helping you to think about how this might be reflected in your own personal curatorial practice after critically examining the interactive elements of an exhibition.

Depth of Content

The discussion in Week 6, Art in the Anthropocene, touches on environmental art, but the analysis is superficial. It is recommended to refer to Latour (1993) and demonstrate the role of the theory in interpreting contemporary environmental art with practical examples. Also explore the section in Davis, H., & Turpin, E. (2015) where human activity has left an irreversible mark on geological time and artists respond to and reflect on this global crisis. Bringing together interdisciplinary perspectives, including art, philosophy, and ecology, the book provides a theoretical framework for interrogating how artworks reveal, comment on, and intervene in key topics of the Anthropocene period. It will deepen readers’ understanding of the complex motivations behind environmental artworks and reveal the potential power of art in the current context of ecological crisis.

Visual presentation

The blog’s use of images appears relatively conservative. Taking the first week as an example, there is a lack of visual examples when discussing the Fruitmarket Gallery. Wolfe (2006) discussed the dynamics of images, suggesting that images are not only decorative but can also provoke thought and emotional responses. So be bold in your use of images and even introduce video or interactive elements to enhance the presentation of your blog. However, be sure and ensure copyright security by following strict academic citation norms when using images to avoid infringement issues.

Criticality and Citation

You have a limited scope for citing contemporary curatorial practice and theory. The ‘Art and Technology’ theme in Week 4 refers to the interaction between art and technology but lacks a multi-dimensional analytical framework. According to Duncan (1995), museums are conceptualized as ritual spaces, providing a framework for analyzing how technology mediates the interaction of the viewer with the art, and incorporating ideas such as these will demonstrate a thorough analysis of your subject matter.

References:

Acord, S. K. (2010) Beyond the Head: The Practical Work of Curating Contemporary Art. Qualitative sociology. [Online] 33 (4), 447–467.

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial hells : participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. 1st edition. London: Verso.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. (2002) Relational aesthetics / Nicolas Bourriaud ; translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods with the participation of Mathieu Copeland. Dijon: Les Presses du réel.

Davis, H. & Turpin, E. (2015) Art in the Anthropocene : Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. [Online]. Open Humanities Press.

Duncan, C. (1995) “THE ART MUSEUM AS RITUAL,” in Civilizing Rituals. [Online]. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 17–30.

Latour, B. & Porter, C. (1993) We Have Never Been Modern. 1st edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wolfe, P. (2006) WHAT DO PICTURES WANT? THE LIVES AND LOVES OF IMAGES. W. J. T. Mitchell. Art documentation. [Online] 25 (1), 72–72.

WEEK 9 | Curatorial project management and fieldwork at Talbot Rice Gallery

Pre-Class Prep, Class Content and Post-Class Investigations

Before the Week 9 class, I examined The Talbot Rice Residents, the Friedlander Foundation’s project, and Candace Lin’s Animal Husbands. They all aim to support artists and promote public engagement, but there are differences in focus. The Talbot Rice Residents emphasize the support and growth of the local arts ecosystem. I inquired after the class that strengthening local arts ecosystems is key to building community identity and cultural sustainability (Bradburne, 2001). According to Art Fund, individuals who participated in local arts activities reported that these activities significantly enhanced their sense of belonging to their community and their perception of community vitality (Art Fund, 2023).

Talbot Rice Gallery,2022. Talbot Rice Residents 2022-2024 | OpenCall YouTube.

Alaya Ang, 'IRVING BERLIN', 2017 (at blip blip blip, Leeds)

The importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in arts promotion is compared to the Freelands Foundation’s (n.d.) approach to promoting arts practices through education and interdisciplinary collaboration. Tate Modern works with programs in the Science, Technology, Arts, and Maths (STEAM) fields, with one event in 2018 attracting over 10,000 participants, most of whom said it was their first visit to an art gallery (Tate, 2018).

Candace Lim’s Animal Husband (Talbot Rice Gallery, 2024) demonstrates the potential of art to inspire society through artistic interventions that challenge conventional understandings of history and biology. This echoes Nicolas Bourriaud’s argument in Post-Production that contemporary art stimulates social reflection by facilitating interaction between viewers and social interaction. Through participatory art practices, Lin’s works ask viewers to actively engage with and interpret them, thereby facilitating exploration and reflection on a wide range of socio-cultural issues, embodying Bourriaud’s emphasis on the role of art as a medium for social and cultural interaction.

These are more international perspectives than the Talbot Rice Residents and the Friedlander Foundation. The comparison leads me to consider the balance between local and global perspectives in curatorial practice. While supporting local art ecosystems is critical to the growth of artists, contemporary art should also serve as a global dialogue to challenge our worldviews.

During the class I went into the Talbot Rice Gallery to experience cross-cultural dialogue and multiple perspectives in curatorial practice, and Bishop (2012) suggests that contemporary curating needs to go beyond the exhibition itself to become a medium that inspires public engagement and social reflection, which corresponds to Candace Lin’s Animal Husbands exhibition on participatory art and its use of audience participation and space.

Later on, ADAM’s tutor’s talk on curatorial project management reflected that curating is not only about art presentation, but also a complex project management practice. This includes precise planning of timelines, space utilisation and budget management. I mapped the conceptual counterparts of these to my personal projects. With a single word limit, I will put the personal project in the next blog in week nine.

Content of the group workshop

During the collective research process, we established and discussed the group’s name around Pili Pala, which aims to explore the stimulation of cross-cultural communication through art. The discussion reflected an understanding of curating as a social practice and cultural intervention. By analyzing all curatorial values such as interculturalism, sustainability, and social responsibility, we highlighted that curating is also a platform for social dialogue and change.

Furthermore, our curatorial practice is inspired by O’Doherty’s (1976) spatial theory (transforming the gallery space into a field of communication and interaction). We developed the project named Domino Project and explored how to promote audience engagement through art making and exhibition layout.

References:

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial hells : participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. 1st edition. London: Verso.

Bradburne, J. (2001). A new strategic approach to the museum and its relationship to society. museum Management and Curatorship, 19(1), 75-84.

ODOHERTY, B. (1976) INSIDE THE WHITE CUBE – NOTES ON THE GALLERY SPACE .1. Artforum. 14 (7), 24-30.

Graburn, N.H.H. (2014). The Anthropology of Tourism: Heritage and Perspectives. pennsylvania: Channel View Publications.

Talbot Rice Gallery. (n.d.). Talbot Rice Residents. [online] Available at: https://www.trg.ed.ac.uk/residents-1 [Accessed 20 March 2024].

Freelands Foundation. (n.d.). Freelands Artist Programme. [online] Available at: https://freelandsfoundation.co.uk/partnerships/freelands-artist-programme/ [Accessed 19 March 2024]. March 2024].

Talbot Rice Gallery. (2024). Candice Lin: The Animal Husband. [online] Available at: https://www.trg.ed.ac.uk/exhibition/candice-lin-animal-husband [Accessed 20 March 2024 ].

Art Fund. (2019). The Impact of Art Funding on Local Communities. [online] Available at: https://www.artfund.org/our-purpose/news/five-museums-shortlisted-for- art-fund-museum-of-the-year-2023 [Accessed 19 March 2024].

Tate.(2018). STEAM Projects and Public Engagement. [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk [Accessed 18 March 2024].

WEEK9|Curatorial Venue, Timeline and Budget Second Update

Timeline: After reflecting on the exhibition cycle of the Talbot Rice residents, I realized the impact of time management on the fluidity of the exhibition and the interaction between artist and audience (Turner, 2009). Echoes in Blue began 4 months ago, incorporating project planning theories discussed in class, setting research and design phases, identifying artists and directions for the work, and embodying a project initiation strategy. As the project progresses over the 2-4 month period, the spatial layout and artist collaborations must be closely aligned. 1-2 months prior, in terms of promotion and audience engagement strategies, I refer to best practices in marketing and public engagement (Simon, 2010) to ensure that technical support is in place and that the audience experience is appropriate.

Spaces: Through the physical layout of the Talbot Rice Gallery, I recognized that the choice of space should serve the core themes and objectives of the exhibition, and my project aimed to explore the traditional elements of blueprint culture and provide an interactive experience through modern technology, so the interior was more manageable. It not only protects the environmentally vulnerable blueprints but also provides technical support and a focused visitor experience. In terms of the health and safety assessment of the space, my curatorial project incorporates multi-person participatory art practices that are more stable indoors independent of the climate.

I eventually settled on Dovecot Studios for the exhibition. Originally a Victorian bathroom, this has been transformed into an internationally renowned tapestry studio and a center for contemporary art, craft, and design. It offers a unique and adaptable space suitable for events such as workshops. The location’s rich historical background and cultural ambiance, coupled with its expertise in art making, made it the ideal venue for me. Dovecot Studios offers a variety of event spaces that can accommodate between 20 and 250 guests, catering for multi-person collaborative projects. My choice of space thus not only reflects the core theme of the project but also takes into account the stability of the health and safety assessment (Kwon, 2014).

So far I have found their phone number and email.

Tel: +44 (0)131 550 3660 Email: info@dovecotstudios.com

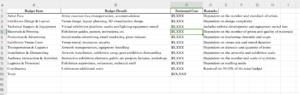

Budget: With limited resources, effective budget management becomes critical to the success of the project (Bilton, 2007). I have outlined the following budget table:

Budget Table for the "Echoes in Blue" project. Source: Own creation (Lu, 2024)

Funding: Exploring the importance of different funding sources and their impact on project support is based on an understanding of the Friedlander Foundation’s grant program. The following organizations have been identified as potentially available for sponsorship: Edinburgh Chinese New Year Festival Organisation, Chinese Culture and Arts Institute (CCAI), Chinese Embassy in the UK, private sponsorship and crowdfunding platforms (Kickstarter, Indiegogo), British Council, University of Edinburgh, Creative Scotland.

British Council. (2024). Connections Through Culture. Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.org/arts/connections-through-culture

British Council Arts (2023). "British Council: Building connections through arts and culture" [Video]. YouTube. Available at: https://youtu.be/AZMaSHKjtPI

British Council. (2024). Arts Opportunities. Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.org/arts/opportunities

Chinese Cultural Arts Institute. (2024). screenshot. Available at: https://www.chineseculturalartsinstitute.org/

References:

Bilton, Chris. (2007) Management and creativity : from creative industries to creative management / Chris Bilton ; [with a foreword by Lord Puttnam]. Malden, Mass. ; Blackwell.

Kwon, M. (2014) “One place after another: Notes on site specificity (1997),” in The People, Place, and Space Reader. [Online]. pp. 27–33.

Simon, N. (2010) The participatory museum / by Nina Simon. Santa Cruz, California: Museum.

Turner, J. R. (2009) The handbook of project-based management: leading strategic change in organizations. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

WEEK8|constructing narrative power and interaction in place-specific art

Class Resource Readings and Post-Class Independent Study

Place-specific art not only taps into repressed histories and provides greater visibility to marginalized groups and issues, but also interrogates place’s social and historical dimensions (Kwon, 1997). By situating artworks within wider cultural and social contexts, as mentioned in Contextualization, artists, and curators have begun to explore how they can intervene in the public sphere and community life through their artistic practice (Doherty, 2009). However, how do you ensure that art projects truly reflect and respond to the needs and aspirations of the community, rather than simply using the community as the context or object of art practice? I think it exposes the challenge of achieving this understanding in practice: how to avoid the potentially exploitative and superficial involvement of arts projects in communities, and to ensure that arts practice contributes to genuine social dialogue and change, is something that must be seriously considered as site-specific arts continue to evolve. In addition to this, we explored the concepts of site-responsive and site-sensitive art, and how they can affect the audience experience.

I independently researched Julie Louise Bacon’s curatorial project on artists exploring the relationship between time and place as a means of influencing human perception and action, Habitat of Time (Arts Catalyst, 2020), as this echoed the course’s focus on artists and curators intervening in the public realm and community life by situating artworks in wider cultural and social contexts. public realm and community life by placing artworks in a wider cultural and social context. The works I viewed in the exhibition included James Guerts’ Trajectories II-Prebiotica (geological and cosmic dimensions of time using ancient meteorite material) and Robert Andrew’s Detail of Disruptive (Ill) Logic (symbolic of the power of materials and technology to shape relationships with time), both of which explored the power of materials and technology to shape relationships with time. and Robert Andrew’s ‘Detail of Disruptive (Ill) Logic’ (symbolizing the power of materials and technology to shape relationships with time), both explore the multidimensional experience of time, presenting the plasticity of time while suggesting its relevance to geological, technological, biological and cosmic scales. This multidimensional conception of time overturns anthropocentric understandings of time and proposes a conception of time that is deeply interconnected with the non-human world. This directly echoes the content of this week’s course that I mentioned at the beginning. The exhibition demonstrates the multidimensional nature of the site’s physical characteristics, historical context, and other characteristics interacting with the artwork.

Robert Andrew, detail of Disruptive (Ill) Logic, 2017, pearl shell, rocks, etched blue stone, ocher, iron oxide, tree branches, string, 240 × 240 × 280 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Arts, Brisbane

James Geurts, Trajectories II-Prebiotica, 2019; image courtesy the artist

Group Workshop with CAP students

Assigned to GroupA, I had the pleasure of discussing with fellow Contemporary Art Practice student Siri about potential exhibition venues for her curatorial theme ‘Holy Collection’. She seeks to enhance audience engagement with her work by presenting it in a location that is closely related to Scottish folklore. I believe that the Anatomy Museum at the University of Edinburgh, with its unique historical context and the echo of the concept of ‘artifacts’, provides an ideal space for Siri’s work (Kwon, 1997). This is because Siri aims to convey folktale meanings through material forms such as ceramic plates, which resonate with the Anatomical Museum’s attributes as a witness to history. The unique environment of the Anatomy Museum stimulates the audience’s curiosity and desire to explore the subject matter of the exhibition. At the same time, the ambiance and historical depth of the venue was able to enhance the attractiveness of the work, thereby increasing audience engagement. The rest of the group mentioned that historic buildings or modern art spaces in Edinburgh’s New Town, for example, could also provide Siri’s project with an environment with fluidity and diversity in time and space (Bishop, 2005).

University of Edinburgh. (2019). Anatomical Museum Virtual Tour. Available at: https://www.ed.ac.uk/visit/museums-galleries/anatomical (Accessed: 17 March 2024)

References:

Arts Catalyst. (2020). The Habitat of Time. [Online] Available at: https://www.fact.co.uk/news/2018/04/dr-julie-louise-bacon-visits-fact-from-sydney-as-part-of-major-international-research-project (Accessed: 20 March 2024).

WEEK7 | Glasgow fieldwork deeply intertwined with archives

My fieldwork in Glasgow in week 7 allowed me to re-examine the interrelationships between art, history, and archival practice in a new light (Igwe, 2019). In particular, at ‘The Trembling Museum’, Dominic Paterson and Andrew Mills demonstrated how nonnormative time is represented in archival practice. This breaks through the confines of linear narratives to show the layering and interweaving of time, forcing us to reconsider the ways in which historical events are presented and how they interact with the reality of the viewer’s life (McMahon, 2023). At the same time, Igwe’s reconstruction of historical narratives through film archives highlights the potential of archives in documenting and reflecting on the histories of marginalised groups (Igwe, 2019), offering a fresh approach to archival interpretation.

The CCA Glasgow visit further deepened this understanding as Rae-Yen Song pushed the boundaries of life and death narratives, further confirming the value of archives as a dynamic resource that can inspire new understandings of life, death, and memory (Song, 2022). At the final stop, Glasgow Women’s Library, the experience of feminist archival practice emphasized the role of archives not only as recorders of history but also as catalysts to inspire social change and promote gender equality in the future (Gaudsen, 2022).

I therefore reflect on how curatorial practice can more creatively utilise archives to activate non-normative time to provide a more interactive and pluralistic view of history. In An Archival Impulse, Hal Foster discusses how modern artists have transformed the archive into an active medium for re-examining the past and the future by excavating the historical omissions and cracks in the archive (Foster, 2004). This echoes Jacques Derrida’s insight in Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression that the interpretation and construction of the archive is an act of power that influences the formation of memory and history (Derrida, 1995). Combining Foster’s artistic perspective with Derrida’s philosophical analysis, I have come to understand that archives are not only records but also key tools for shaping historical perspectives, memories, and identities, reflecting the past while engaging in current cultural dialogues and the construction of future histories (Stearn, 2022).

The peer-to-peer advice given to all members by tutor Adam in this week’s seminar not only applies to individual student projects but also sheds light on my curatorial project. The seminar emphasized on the principles of layout, visualization, and overall design; it also touched on the organization and archiving of archival materials; and the selection of socially significant artworks. Feedback on my project focused on the dialogue between tradition and modernity, and I was advised to explore modern curatorial approaches by looking at multiple media, virtual exhibition platforms, and social media promotion. The focus was also on curatorial practice and textile technology. I gained new insights into traditional and contemporary curatorial practices after reading the recommended book Old Mistresses (Parker, R. & Pollock, G., 1981). By incorporating curatorial feeding into curatorial practice, it is possible to communicate more effectively with audiences from different backgrounds and present blueprints as a powerful form of cultural expression through richer forms of content and exhibition strategies (Williams, 2021).

Progress on group projects

After an offline group workshop, Ningyue shared Feng boyi’s books on writing domino plans (Figures 1) to use as our inspiration. My personal research revealed that all the works in his curatorial project would be in an unfinished state, where people and works, environment and works, and people and environment are all influencing each other, and everyone is both a participant and a judge of the works, being outside of it and difficult to escape from it (Art China, 2009). After discussion, our group plans to incorporate the content of the book, with proper citation, into the group project Forehead.

‘Is there a brand new curatorial approach that makes full use of both social and physical space to showcase a facet of contemporary art, while transcending conventional methods and itself by presenting the processes, questions, and indications?’

Boyi Feng, 2009

References:

Derrida, J. (1995). ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.’ Diacritics, 25(2), 9-63.

Foster, H. (2004). ‘An Archival Impulse.’ October, 110, 3-22.

Gadsden, C. (2022). Glasgow Women’s Library: A Feminist Archive Practice. Glasgow Women’s Library.

Igwe, O. (2019). ‘The names have changed, including my own and truths have been altered.’ [Film] London.

McMahon, L. (2023). ‘Disordering archives: Onyeka Igwe and Black feminist speculative histories.’ Screen, 64(4), 377-400.

Song, R.-Y. (2022). Life-bestowing cadaverous soot. CCA Glasgow.

Stearn, E. (2022). ‘Feel My Love.’ Lothian Health Services Archive.

Art China. (2009). ‘The Domino Project in Space: The Domino Effect on Memory. China Art Network. [Online] Available at: http://art.china.cn/huihua/2009-06/17/content_2966895.htm