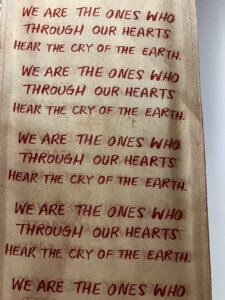

“We invite humanity to this collective task. To assume this commitment to reforest minds and hearts for the healing of the land, and to retake the relationship of the land as a relative; as a mother, as a grandmother, and not as a commodity”

Célia Xakriabá, Indigenous educator and activist of the Xakriabá people of Brazil

It is time for designers to start taking responsibility. Our western lifestyles have relied on resource extraction and polluting processes to feed our toxic obsession for profit for far too long. It is time to let go of our brutal capitalist egos and transition to a ‘kinder’ and more respectful relationship with nature. As a result of our selfish actions, we have disconnected a large majority of the World’s population from the earth’s natural systems and rhythms, many depend on these for survival, and this has disproportionately affected the people who are least to blame for this environmental destruction (Grant, 2018).

As a geographer, I have become increasingly aware of the importance of incorporating indigenous knowledge systems into the physical, cultural, and social understandings of the planet and have studied the devastating impact of climate change and capitalist activity on indigenous populations. This week’s content inspired me to view these understandings in a different light, imagining a world where indigenous knowledge systems are central in design approaches and decision making. If we were to acknowledge the many different ways we could design for a more sustainable and ecologically secure future, then perhaps we would incorporate traditional knowledge and teachings into our design disciplines.

Indigenous populations understand the Earth’s environmental complexities and place conservation and regeneration at the heart of their practices and ways of living (Reitsma et al, 2019). They acknowledge potential of Earth’s resources while valuing and respecting their existence without exploitation (Akama et al, 2019). They do not see humans as superior to nature, unlike in our western hierarchy, and instead view humans as merely a small part of the Earth’s organisation (Stewart, 2015).

I recently came across indigenous artist and architect, Joar Nango who identifies as part of the Sámi indigenous people of Northern Europe. Nango is one of the few practising Sámi architects, and his work actively attempts to create a feedback loop between past and future architectural narratives (Zeiger, 2020). He aims to find the intersection between indigenous and contemporary in order to create and build harmonious designs and constructions (Zeiger, 2020). What drew me to exploring more of Nango’s work was the importance he places on addressing the relevance of indigenous cultures in design discourses. He emphasises that as designers we cannot simply take the techniques and practices of these traditional knowledge systems, extracting their technologies and innovations, instead we must work collaboratively with indigenous communities. We must work alongside them to ensure they are too part of the decision making and will benefit from this sharing and exchange of design knowledge (Zeiger, 2020).

This felt especially important to me as I am currently working on a research project with indigenous graffiti artists from Brazil. Many highlighted the neglect and mistreatment of their peoples, erosion of their heritage and traditional practices, and stressed the reluctance of many to listen to indigenous voices when it comes to the serious matter of safeguarding the future of the planet. I now appreciate how vital such collaborations are, as the Earth’s resources continue to deplete and climate change worsens. Designers need to adopt more sensitive approaches to nature and landscapes, using local grounded materials native to site specific regions, and incorporating indigenous climate adaptation techniques into their work (Reitsma et al, 2019).

Indigenous communities comprise “less than 5% of the world’s population, and yet they protect up to 80% of the Earth’s biodiversity” (World Wildlife Fund, 2020). Their partnership with nature is one of mutual support, where they defend and take care of the natural systems they depend on, without mistreatment. It is time we adopted this same approach in the West and take our overdue responsibility more seriously.

References:

Akama, Y., Hagen, P. and Whaanga-Schollum, D., 2019. Problematizing replicable design to practice respectful, reciprocal, and relational co-designing with indigenous people. Design and Culture.

Grant, E., Greenop, K., Refiti, A.L. and Glenn, D.J. eds., 2018. The handbook of contemporary indigenous architecture (pp. 1-1001). Singapore: Springer.

Reitsma, L., Light, A., Zaman, T. and Rodgers, P., 2019. A respectful design framework. Incorporating indigenous knowledge in the design process. The Design Journal, 22 (sup1), pp.1555-1570

Stewart, P.R.R., 2015. Indigenous architecture through indigenous knowledge: dim sagalts’ apkw nisiḿ [together we will build a village] (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

World Wildlife Fund, 2020. Recognizing indigenous peoples’ land interests is critical for people and nature. WWF. Available at: https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/recognizing-indigenous-peoples-land-interests-is-critical-for-people-and-nature#:~:text=By%20fighting%20for%20their%20lands,they%20have%20lived%20for%20centuries (Accessed: 24 November 2023)

Zeiger, M. (2020) Interview: Joar Nango on Indigenous Architectures and slippery identities, PIN. Available at: https://archive.pinupmagazine.org/articles/interview-mimi-zeiger-joar-sami-architecture-joar-nango (Accessed: 27 November 2023).