The concept of ‘vibrant matter’ proposes that all elements in the world, from matter to materials, from objects to ‘things’, possess vitality and agency, giving them intrinsic value. Bennett’s (2009) book “Vibrant Matter”, advocates for a shift of perspective away from the human-centric view of human beings as primary agents in the world, and non-human entities as passive and devoid of influencing or impacting on us or our surroundings. Instead, Bennett wants us to see ‘matter’ as having the potential to actively shape and assert agency, what she refers to as “thing-power” (Bennett, 2009, p.2).

The attribution of value we give to objects and materials is a consequence of our social construction of meaning. However, as we mindlessly consume things, we frequently regard the nature of the matter itself as insignificant. If we were to recognise that humans and objects had the ability to equally enact and exert agency and that the material things surrounding us are in fact ‘vibrant’ in their nature, then perhaps we would rethink our relationship to, and treatment of, material stuff and thus the ecological and social decisions we make.

Today’s reading group discussion culminated in a conversation about children’s toys and the role that material objects have in children’s narratives of play. When asking the group about meaningful toys they had as children, one member referred to a particular rag that came from a kitchen tea towel. The rag did not resemble a conventional toy, nor was it reconfigured into something ‘human like’, it was simply a tea towel end and yet to her it transformed itself into a powerful companion that embodied immense meaning, safety, and pleasure. She was able respond to its ‘vibrancy’ and create her own unique stories of play with it.

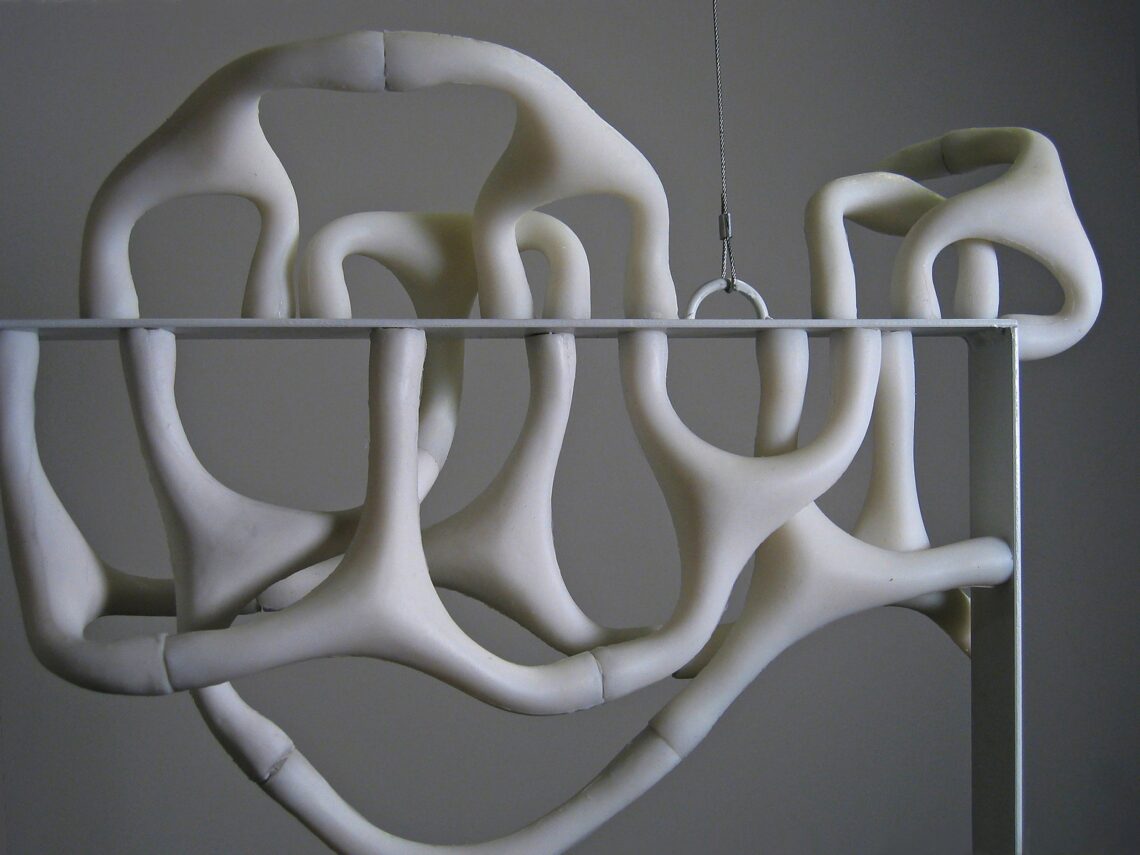

This reminded me of Cas Holman’s Geemo, a child’s play companion that takes the form of magnetic limbs that can be attached together to form unique and irregular patterns and structures. The limbs are not colourful and do not have human attributes, they are abstract, however they have vibrancy and are vital actants in the process of being transformed with children. They can link, repel, attract, grow, crawl etc in unpredictable ways as they co-construct with children to create distinctive imaginative configurations.

To children, objects and materials are anything but passive, matter can collaborate with a child and visa versa allowing both to socially co-construct their own meanings and realities when playing. Both the material and child rely on one another to create powerful moments of storytelling (Thiel, 2015). This example reflects Bennetts concept of “vital materialism”, ‘things’ become vibrant when they have the intention to incite something or entice us to do something (Bennett, 2009). Instead of perceiving objects as ready to be played with and simple subject to alteration and manipulation, Bennett encourages us to view objects and humans as both mutually adaptable, where both can engage in a collaborative process of shaping (Lenz-Taguchi, 2014).

References:

Bennett, J., 2009. Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Thiel, J.J., 2015. Vibrant matter: The intra-active role of objects in the construction of young children’s literacies. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 64(1), pp.112-131.

Lenz-Taguchi, H., 2014. New materialism and play. In Blaise, M., 2014. Gender discourses and play. The SAGE handbook of play and learning in early childhood, pp.115-127.