Reading design historians, Kjetil Fallan and Finn Arne Jørgensen’s, article encouraged me to think in more depth about the complex intersection of design history and environmental design and the importance of moving beyond seeing our damage to the world in simplistic terms as “once whole, but now broken” and instead “consider it always-already broken” (Fallan and Jørgensen, 2017, p.117). To do this they advocate that a change in mindset is required in order for us to understand the impact design has on our connection to, and treatment of, the natural world. One section of the article that stood out for me was the author’s discussion on consumerism, the cultural connotations and meanings associated with material objects in a consumerist society. Our perceptions of the status of material objects can change in relation to the level of environmental consciousness of a society. For example, initially the pink plastic flamingo was a symbol of modernity, when plastic was heralded as a new revolutionary material, however the growing environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s raised awareness and the pink flamingo, along with plastic in general, went on to represent our disconnection from nature and symbolise the artificial.

This lead me to reflect on the act of commodifying nature in a consumerist culture. In an era of global mass production, we have progressively distanced ourselves and become increasingly disassociated from the materials that comprise our consumer products. We think less about the origin of each component in a product, nor the methods employed to extract these from their natural sources. We think even less about the energy used to combine these materials into a single product. Consequently, what we see is a loss of the intrinsic value of our consumer goods, as they appear as something easily replaceable and ubiquitous. When we begin to view nature as just another ‘consumer product’, something always abundant and accessible, we believe we can exploit it endlessly, viewing it as self-replacing. This alters and distorts our relationship and perception of nature, affecting how we use and treat the natural world and its resources. Our mass-produced consumerist society has had a harmful impact on the human psyche, threatening to erode not only our cultural appreciation of nature, but also our spiritual connection with the natural world. This is having devastating consequences for the future of the Earth’s systems and our dependancy on them.

I was reminded of the recent ‘DRIFT’ exhibition I visited in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The artworks aimed to help people re-establish their connection to nature with a number of different approaches. One particular work, entitled ‘Materialism’, made me rethink my own relationship with consumer products.

‘Materialism’ works to reveal the dimensions of the materialism these systems feed, illuminating the excessive use of the earth’s gifts, irreplaceable matter that humans incessantly rip away from it, squander, and then dispose of with little thought (Drift, 2023).

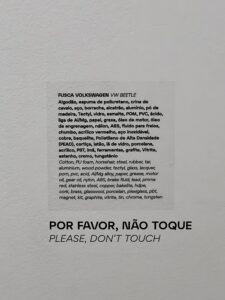

Materialism ‘reproduces’ familiar everyday objects, ones that we tend to consider only their aesthetic or function, and strikingly breaks each item down into quantified blocks of each individual material component. This starkly demonstrated the different materials and quantities required from the earth resources to produce each mass produced product. As I observed objects such as teddy bears, a VW Beetle, an iPhone, a machine gun, a flipflop etc reproduced in their separated material forms, it forced me to appreciate just how much of our natural resources are required to satisfy our pervasive capitalist system. I found it shocking and extremely important as it bought into uncomfortable focus my own impact as a consumer.

If humankind could somehow perceive this connection to materials, to the collective consumption and the earth it impoverishes, it would be a leap in our social evolution, in building an awareness that everyone must somehow become better stewards of the future (Drift, 2023).

References:

Fallan, K. and Jørgensen, F.A., 2017. Environmental histories of design: towards a new research agenda. Journal of Design History, 30(2), pp.103-121.

Yulia Kovanova

13 November 2023 — 19:22

It is a striking-looking blog overall, with good use of images and references. Good observations on commodifying nature in a consumerist culture and the issues arising from this. Where do you reckon solutions might come from? How could design be a part of this solution? Great use of examples from your gallery visits.