1.5 Working with the South American Skull Collection (Pt. 3)

As a part of our project brief, we were asked the following question: what strategies can be employed to address knowledge and metadata gaps in small museums? To address this problem we began work in Semester 1 with Ruth Pollitt, one of the curators of the Anatomical Museum. Over the course of the semester, we met with Ruth biweekly to catalogue and further research the skulls in the South American collection of the Skull Room. This work included basic cleaning, photography and measuring of the skulls, followed by research into the phrenological catalogues and museum catalogues to try and find further information on each individual. This information was then compiled onto an online spreadsheet which allows for researchers on the collection to easily access the most up to date and accurate information regarding the South American collection.

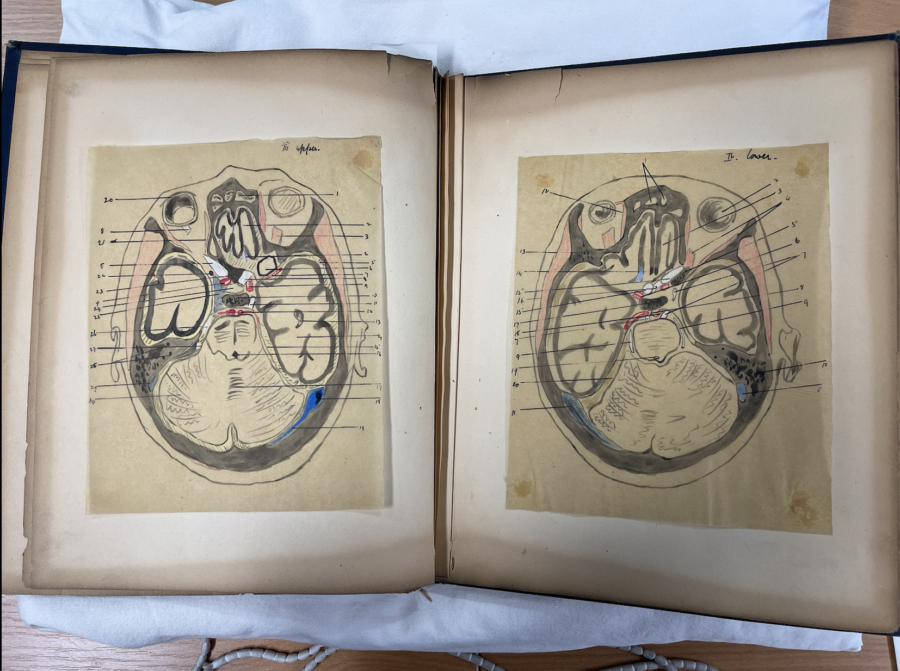

Page from a phrenological catalogue which details information on the acquisition/origin of the South American skulls.

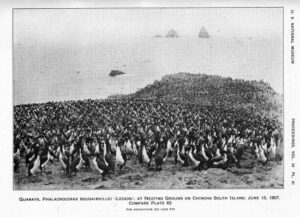

This experience was incredibly insightful to the development of our final project delivery. Seeing how the museum works, and what type of research is currently being undertaken by curators helped me to better understand the importance of meaningful and careful curation. Each skull was handled incredibly carefully, and Ruth was always nearby to provide us with support or to answer any questions which we may have had. The final two sessions with Ruth I chose to focus my time on further researching the origins of a young adult from Peru, whose skull had ended up in the museum’s collection but had little to no information to corroborate its provenance. The only information available for this particular skull was a catalogue entry which described the individual as being Peruvian in origin, from the Chincha Islands, and the word guano followed after this. After some initial research, I quickly discovered that guano was fertiliser created from seabird excrement. After chatting with Ruth about this, I began digging deeper into why this individual would have this associated with their skull and how this relates to the Anatomical Museum in Edinburgh.

The only available information I could find online was a newspaper article from the later 19th century which discussed the import of guano into the Port of Leith here in Edinburgh. The article stated that often times human and animal remains could be found within large shipments of the fertiliser. While it is difficult to say with certainty, it is possible that the young adult from Peru was discovered within the contents of a guano shipment to Edinburgh and was donated to the museum. The Chincha Islands, where the skull was described as originating from, were the largest exporter of guano to the United Kingdom in the 19th century.

Photograph of seabirds on the southernmost Chincha Island in Peru, 1907. (National Museum of American History [Online]).

Unfortunately, I hit a wall with my research and was unable to find any additional information which could tell me more about the life of this individual and why they ended up in the Skull Collection. Ruth explained that this is typical when handling material of this age, and which was collected with derogatory and racial motives. From this, I was able to better understand the realities of working in a small museum, and the frustrations which arise when trying to provide dignity to the individuals within the collection. My time working with the South American Skull Collection was incredibly meaningful and impactful for me. I had a desire to provide a glimmer of justice to this young adult from Peru, but was met with challenges in finding accurate information regarding the acquisition of the skull itself. Nonetheless, the information I could compile was successfully added to the working spreadsheet which Ruth had begun, and will hopefully be of use to researchers moving forward.