1.3 Thematic Analysis: the Decolonial Museum

Our project, Face to Face: Approaching the University’s Skull Collection, is deeply rooted in practices of decolonial theory and curatorial work. When handling objects in a collection that have been illegally or wrongfully acquired, one must ask the question: Whose stories are we truly telling? In the case of the skull collection, it has traditionally been the narratives of the colonisers being told over those of the individuals themselves. Outdated and racist texts accompany this collection, and our project now redirects the focus to the stories of the individuals who are resting within: who they are, where they came from and how we can display them in the most respectful way possible moving forward.

Museums have never been and will never be neutral spaces. The concept of the museum is rooted in colonial and imperial notions of humanity, with the display of often-times stolen artefacts at the forefront of comparisons between us and them. As modern curators, we are tasked with resolving outdated modes of display from the past, while also engaging seriously with the communities and individuals our museums are representing in the future.

In order to fully understand the breadth of colonial practice within many museums today, I began researching the work being undertaken by the Museum of Ethnology in Hamburg (MARKK), Germany. This museum exemplifies the work being done by institutions abroad to rectify and address their pasts as places of colonial practice, theft and stereotyping. The museum’s webpage not only charts the history of the institution in great detail, but also has a dedicated platform for addressing its colonial heritage. MARKK works closely alongside modern descendants of the community groups targeted during the height of empire across Europe, and opens up dialogues surrounding restitution, display and public engagement with their stolen cultural heritage. The project ‘Digital Benin’ was launched by the museum in 2020 as a means of connecting artefacts from the Kingdom of Benin onto a single digital platform. Working alongside institutions in America, Nigeria and Western Europe, the project proactively tells the narrative of the Kingdom of Benin through its material remains. The aim of Digital Benin is to broaden the scope of knowledge available to the public, while also allowing for descendants of the Benin community to engage more closely with their own ancestral material.

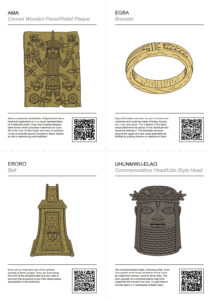

This goal shares a similar vision to our own project, Face to Face. The Skull Collection within the Anatomical Museum at Edinburgh University is not open for public display, with many individuals unaware of the presence of this collection all together. Making the collection public knowledge was an important step for our project, as it allows for diverse audiences to input their ideas and thoughts on the future of the collection moving forward. Especially important is the use of this knowledge by local community groups such as The Sudanese Community in Edinburgh, which is led by one of our event speakers, Zaki El-Salahi. It is crucial that museums entrenched in colonial practice, such as the Anatomical Museum and MARKK, actively seek out local communities who are directly affected by the museum’s past to learn more about and speak directly to their thoughts and feelings on the collections we hold. The collaborators on the Digital Benin project shift the focus of the objects from that of ethnographic spectacle to objects of ancestral importance. The webpage includes a section on the oral histories of objects, as well as a label library which teaches audiences the correct Edo classifications of objects.

An example of the Edo classification system from the Digital Benin webpage. (Amadusan, 2022).

Museums are deeply rooted in practices of theft, racial stereotyping and outmoded hierarchal classifications dating back to the age of empire. Following on from our event, we asked our audience what they felt should be done with the Skull Collection in the future. A majority of these responses suggested repatriation efforts as the best step forward in humanising the collection. However, the intricacies of repatriation mean that this is not always a suitable avenue of resolution for a museum or community group. Barriers such as lack of funding and the current legislation which requires government officials to begin this process means that many collections remain untouched despite a desire by the curators to resolve their colonial past. Digital Benin is an excellent example of a decolonial museum which not only addresses its role both past and present in instigating harmful colonial thought, but also realises the importance of collections care and management as an avenue of restitution. Unfortunately, many objects from the Kingdom of Benin were looted in the 19th century, creating a diaspora of artefacts which expand across the globe. It is unlikely that these objects will ever be physically unified in person, therefore work such as the Digital Benin project allows for audiences to fully understand the extent of a collection without the need to visit in person or to return objects.

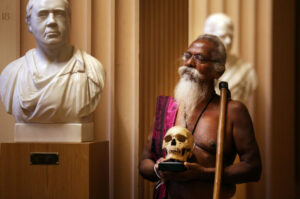

The university’s Anatomical Museum has had success in a previous repatriation project to the descendants of the Vedda community in Sri Lanka. However these process take time and careful negotiation and considerations. Hence, events like Face to Face bridge the gap in action between an objects collection and eventual return. By spreading knowledge and handing the microphone over to specialist speakers, we have been able to generate greater understanding and awareness of the Skull Collection without moving the individuals from their current resting place within the museum. More work continues to be done within the collection, however our event is a starting point from which real change can occur. Similar to Digital Benin, our Hidden Histories museum tour expands upon the nature of the museum’s displays and sought to express a more humanistic approach to the display of human remains. Despite their differences in subject matter, Digital Benin and Face to Face both share a desire to address a common colonial past, retell the narratives of the collections, and to connect individuals with varying sets of skills and expertise in order to move forward from a harmful past towards a future of greater care, respect and inclusion within museology.

Image of the Ceremonial Return of the Vedda skull to Wanniya Uruwarige, Chief of Vedda. (Cheskin, 2019).

Bibliography:

Amadusan, O. 2022. Ẹyo Otọ Language Cards and Colouring Book. [Online]. [Accessed 6 April 2023]. Available from: https://digitalbenin.org/eyo-oto

Cheskin, D. 2019. Wanniya Uruwarige, Chief of Vedda. [Online]. [Accessed 6 April 2023]. Available from: https://exhibitions.ed.ac.uk/exhibitions/mind-shift/colonial-resistance-to-repatriation

Colonial Heritage. [Online]. [Accessed 6 April 2023]. Available from: https://markk-hamburg.de/en/digital-benin-2/

Divya P Tolia-Kelly 2016. Feeling and Being at the (Postcolonial) Museum: Presencing the Affective Politics of ‘Race’ and Culture. Sociology (Oxford). 50 (5), 896–912.

Gaupp, L. et al. 2020. Curatorial Practices of the ‘Global’: Toward a Decolonial Turn in Museums in Berlin and Hamburg? Journal of Cultural Management and Cultural Policy / Zeitschrift für Kulturmanagement und Kulturpolitik. 6 (2), 107–138.

Henderson, J. 2020. Beyond Lifetimes: Who do we Exclude when we Keep Things for the Future?, Journal of the Institute of Conservation. 43(3), 195-212

Jeffery, T. 2022. Towards an eco-decolonial museum practice through critical realism and Cultural Historical Activity Theory. Journal of critical realism. 21 (2), 170–195.

Lyngwa, A. 2022. Self Representation, Community Engagement and Decolonisation in the Museums of Indigenous Communities: Perspectives from Meghalaya, India. History. 107 (375), 302–321.

Prianti, D. D. & Suyadnya, I. W. 2022. Decolonising Museum Practice in a Postcolonial Nation: Museum’s Visual Order as the Work of Representation in Constructing Colonial Memory. Open Cultural Studies. 6 (1), 228–242.