1.2 Self Appraisal

Identify your key responsibilities and list the main areas of work you have been involved in. Briefly highlight the skills and competencies that are relevant to this project/work area.

1. Project Management:

In the lead up to our event, it was crucial that we met twice a week as a group to review what needed to be done for the week. I assisted in creating meeting agendas and minutes, as well as organising virtual and in person sessions for our group. In addition to this, I created a Google Drive for the project which included folders which housed the material we needed for the event, including email invites, a budget spreadsheet, marketing packs and more. As a group, we created weekly action points which needed to be attended to in order to ensure we were progressing at an appropriate rate before the event. Within group settings, I tend to take a very proactive role, and therefore had to challenge myself to delegate the work equally to create a working environment which catered to the goals and ideas of the collective group.

2. Communicating with Speakers and Partner Institutions:

As a part of our event, we had four speakers and two moderators provide presentations and discussion panels. From the onset of the second semester, I was communicating frequently with our speakers and arranging one-to-one meetings to discuss their goals for the event and what topic they would be presenting on. This allowed me to develop my communication and time management skills, as it was crucial to ensure that our speaker’s were being responded to on time and kept up to date on any and all changes to the event. The sensitive nature of the event context meant working closely with experts such as Zaki El-Salahi, a leading member of the Edinburgh Sudanese Community Partnership. We frequently kept in contact and held meetings with Zaki to ensure that we were approaching this event in the most respectful way possible, and allowing for others to open up the dialogue for conversation on the topic which still resonates closely to many ancestral communities today. Additionally, I worked closely alongside the curator of the Anatomical Museum, Malcolm MacCallum, in order to discuss the ways in which the displays in the museum connect to our event and the Skull Collection more broadly. We established the exhibition title Face to Face: the Hidden Histories as a means of informing audiences of the hidden narratives that are within the museum display cases.

3. Distributing Marketing Packs and Creating an Event Brite Page:

I was responsible for creating the first draft of the marketing pack which we would use to send to institutions and individuals we felt could best promote our event. This included an event blurb, a link to our Event Brite page, as well as pre-written texts for social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. The marketing material was successfully promoted by a range of institutions, including: Surgeon’s Hall Museum, National Museum of Scotland, the School of History, Classics and Archaeology, and Edinburgh College of Art. It was important for our group that the event attracted a diverse audience, including students, heritage professionals, community activists and scientists. In order to achieve this, the marketing material needed to be diligently organised, dispersed to the appropriate groups and proofed multiple times before final submission. After creating the Event Brite webpage for the event, I was able to monitor the number of ticket sales and share the link directly to our guests for ease of booking. Both marketing and webpage management were new skills for me, and required an extensive amount of time management, creativity and background research.

4. Speaking at the ‘Hidden Histories’ Tour:

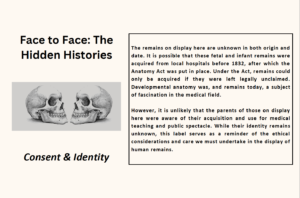

The final component of our event centred around a tour of the Anatomical Museum which was titled Face to Face: the Hidden Histories. The goal of this was to expand upon some of the display narratives within the museum, and to relate these displays to the story of the Skull Collection. For my talk, I focussed on issues surrounding consent and identity within the museum, particularly the display of infant and fetal remains. This involved the creation of a new, alternative label for the display as well as speaking to the audience about the relation of the display to the event. I was required to write concisely while also ensuring that all the relevant information was on display for the label. Additionally, I spoke to members of the audience about the issues surrounding the display, and answered questions surrounding the history of the collection of infant and fetal remains in museums.

Label created for Face to Face: the Hidden Histories museum tour.

Looking ahead, list your key objectives for the GRP. 3-7 SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timed) objectives should be noted with realistic timescales and focused outcomes. The objectives should cover the project itself and your own role.

The main objectives for this project were as follows:

- Tell the complex stories of the Skull Collection from a perspective of decolonial thought and struggle: First and foremost, this event was centered around decolonial museum practice, and seeked to address the complex history of the collection while also providing dignity and restoring humanity to those within it. We achieved this through our selection of speakers, discussion with audience members and tour of the museum.

- Acknowledge metadata gaps in the Skull Collection: During Semester 1, our group. met biweekly with Ruth Baxter, curator of the Anatomical Museum, to bridge our understanding of the collection with hands-on work. We catalogued and researched the South American collection in order to better understand Ruth’s role as a curator, and also to disperse this information onto a spreadsheet for future use.

- Design event structure and host event: Given the complex nature of this collection, it was clear that a traditional exhibition would not be the best route forward for our project. We decided to host an event centred around dialogue as a means of opening up discussions on colonialism within the museum. My title, ‘Face to Face: A Dialogue on the University of Edinburgh’s Skull Collection’ was chosen as the event title, as well as ‘Hidden Histories’ for the museum tour. The planning of the event required constant communication between group members, speakers, and the museum curators. Together, we put together an event which had 50 people in attendance and ignited meaningful discussion surrounding the history and the future of the collection.

- Event evaluation: Following the event, we compiled the data from our surveys and also had a professional illustrator and photographer capture aspects of the day. This information was not only beneficial for our own assessments, but also to help the museum in putting on similar events in the future. The videos and recordings of the event were also compiled and plan to be uploaded to the Anatomical Museum webpage.

My own personal objectives were as follows:

1 . Create a network of communication with our speakers: After months of communication, I was able to establish well-working professional relationships with our speakers. The ability to network with professionals within the field and beyond was deeply beneficial in my understanding of the type of work that goes into hosting an event like Face to Face.

2. Enact real change for the future of the collection: The event sparked discussion amongst many members of our audience, including higher-ups from the university itself. At the reception, I was interviewed by a journalist for Live Science, and was able to explain the importance of conducting decolonial museum practice within university institutions as a means of addressing a wrongful past and making room for improvement and greater inclusion in the future.

Discursive self-reflection

Use this section to, 1) reflect upon the progress of the project to date (both as a whole and with regards to your own specific area/role). 2) Critically reflect upon your experience working with the group. Here you may consider your contribution so far, the value of your specific strengths and expertise, the effectiveness of group communications and your performance in group meetings. How might the group [have] enhance[d] its performance?

Overall, the project was an invaluable experience which proved to be a unique and rewarding challenge for the entire group. Coming from a range of backgrounds, we were all able to utilise our own specialist skills in knowledge in order to create a well rounded event. The group struggled with communication and delegation of the workload at the start of the year, but quickly turned this around by the second semester. My own contributions included proactive leadership, communication with our speakers and partner institutions and engagement with the curators of the Anatomical Museums. My background in conflict archaeology allowed me to view the collection as one born out of colonial thought and theory, something which I personally hoped to express to our audience. I was able to attend every session held by Ruth Baxter of the Anatomical Museum, and gained valuable insight on the inner-workings of the space and the role of the curator in dealing with such complex subject matter. Despite differences in our working styles and opinions on the future of the collection, as a group we all shared a collective goal of humanising the individuals held within the space. I believe our event was a great success in achieving this.