The weather this summer in Scotland has been in many ways idyllic.

Starting in late April we were treated to weeks of sun every day, and consistently mid 20s in Edinburgh. Notwithstanding the test match, it’s fair to say that many would like to see this year’s weather replicated every year. And yet, nature often provides a twist in the tale.

This week someone alerted me to a recent report about the challenge this has posed to farmers – with reduced crop yields, fodder for winter livestock in shortage, and increased costs which are likely to be carried to all of us as a result.

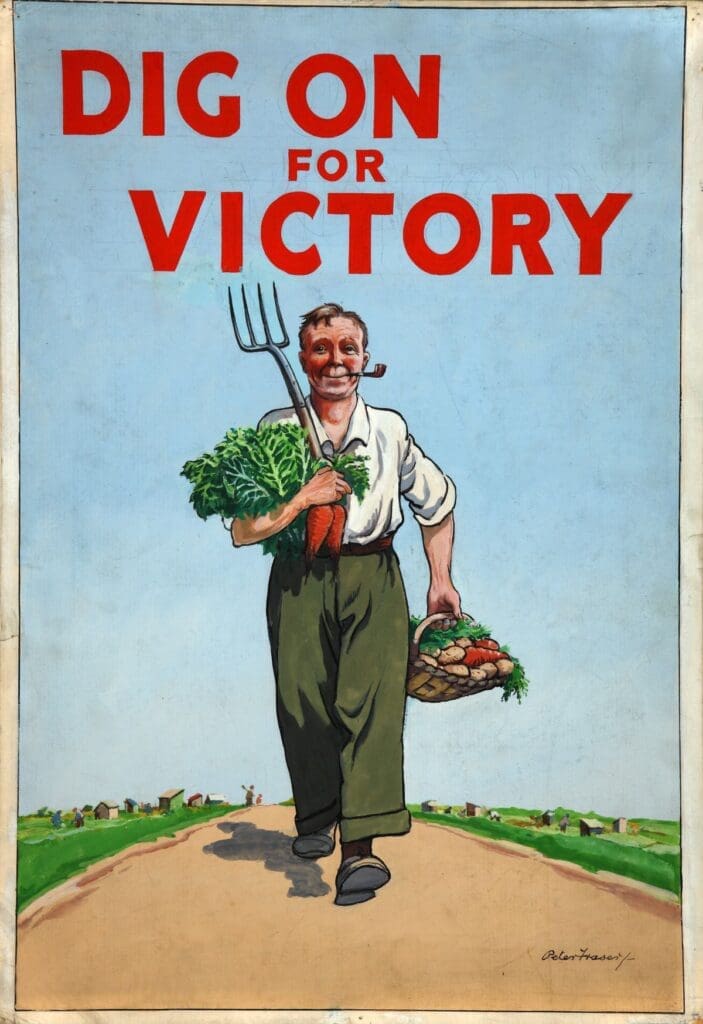

Conversely, I’ve been encouraged this week by visiting one of Edinburgh’s fantastic urban farms, overlooking the Forth. These two themes caused me to consider the UK’s food security and what might be done to improve this.

Climate change at current rate is predicted to mean an increase in average temperatures, combined with intense bursts of rain, more extreme storms and seasonal timing shifts – all of which are likely to replicate this year’s shortages. This year’s challenges may be a foretaste of the future.

If we are to avoid increased imports of food, or even shortages, now might be a good point to survey the ability of the UK to feed itself.

Current UK food resilience

Food security is increasingly recognised as a strategic concern.

The United Kingdom Food Security Report 2021 reports that the UK produces roughly 60 % of domestic consumption by value. It also reports that about 54 % of the food on plates is produced in the UK.

The UK Energy and Climate intelligence unit is forecasting that unusually wet winters (and extreme weather) could reduce UK food self-sufficiency by nearly 10 %.

Three concepts need to be understood if we face into moving this figure into a more posistive direction:

- Climate change, as weve seen, is already disrupting agricultural output via extremes: floods, droughts, hotter summers, erratic rainfall. These increase risks of crop failure and reduce yields.

- Peak oil / energy constraints: Agricultural inputs (including fertilisers, fuel, machinery), processing, and distribution are energy intensive. As fossil fuel prices and availability become more variable, supply chains become more fragile. If we rely on food from far away it will become more expensive to move.

- Resilience demands both the capacity to absorb shocks (weather, supply disruptions, trade instability) and the ability to adapt or reconfigure (by diversifying production, reducing dependencies or building local capacity).

Given these pressures, I’ve pondered whether the UK can feed itself (or get to 90% or even 80% sufficiency) that is, meet nutritional needs with domestic production under adverse conditions and if so, how would it go about this ?

There are some historical and international models, that reach towards greater self-sufficiency and resilience.

Seeking Inspo

- The Local Food Growth Plan in the UK emphasises strengthening regional supply chains, improving local processing and boosting edible horticulture, and embedding local food procurement.

- The Netherlands provides a cautionary example. With limited land and high population density, Dutch agriculture uses high-intensity, high-innovation farming, greenhouse technologies, good logistics, soil & water management, plus strong climate adaptation policy. Their Action Program for Climate Adaptation in Agriculture emphasises soil health, water retention, infrastructure, and nature-inclusive agriculture.

- New Zealand is often held up as a relatively self-sufficient nation. in key food groups like meat, dairy, fruit & vegetables, it performs strongly in self-sufficiency indices.

These models hint that a combination of strong policy, technological innovation, localism, and infrastructure contribute significantly to food self-sufficiency.

What Would Need to Change: Five Key Policy / Practical Shifts

To move toward a UK that is more capable of feeding itself, particularly under stresses, here are five things that would need to change — both in policy and on the ground in local communities:

1/ Set a coherent National Food & Resilience Strategy

The UK needs overarching legislation or strategy that embeds targets for domestic production and self-sufficiency in key categories such as cereals, pulses, vegetables, and fruit, with mechanisms to monitor, adapt, and fund progress. This should integrate concerns around energy, land use, climate adaptation, trade risk. This should include clear self-sufficiency targets and regular monitoring of domestic output.

Proven Impact: OECD (2023) found that integrated national food resilience frameworks improve supply continuity by 15–20% during crises.

2/ Invest in Local and Regional Food Infrastructure ( vs national and international supply chains)

Expand regional food processing, storage, and distribution facilities alongside localised production to shorten supply chains and strengthen local economies and communities. Local food growth plans should be developed and funded in each region, so producers have viable markets locally and are less vulnerable to long supply lines.

Proven Impact: Sustain’s Local Food Growth Plan analysis show a local infrastructure programme increases local food sector capacity and market access by 12–18%.

3 / Reform Agriculture for Resilience (Agroecology & Regenerative Practices)

Move agricultural incentives toward agroecology and regenerative practices that restore soils, reduce dependencies on fossil fuels, and improve climate adaptation to conditions we’ve seen this year and those projected. We know that encouraging crop diversity reduces risk from pests, disease and changing weather.

It’s recommended to incentivise farming practices that reduce dependence on fossil fuel inputs, that support regenerative/agroecological practices and then fund farmer transition support.

Proven Impact: FAO and UK research indicate agroecological/regenerative approaches improve soil water retention, biodiversity and yield stability building on the work of the CCC’s Agriculture Advisory Group which recommends resilience-focused policy shifts.

4/ Diversify Diets & Cut Food Waste

I’ve mentioned the concept of resilience covers both absorption of shock and ability to restructure. Encouraging seasonal, plant-rich diets and halving food waste through public campaigns will help transform our consumption and demand patterns.

The national diet should be more plant-based, include pulses, seasonal local produce; reduce meat where greenhouse gas intensity is high.

Proven Impact: WRAP–Tesco pilot cut waste by 25% whilst the EAT Lancet has demonstrated plant-rich diets reduce pressure on land and imports.

5/ Empower Local Communities & Food Partnerships

5/ Empower Local Communities & Food Partnerships

Expanding local food partnerships, community hubs, and regional procurement networks will strengthen local control over food access and crisis response.

Local governance should be empowered and resourced to map food assets, support urban/peri-urban growing, allotments and community gardens and support education and skills programmes for younger generations in farming, food preservation and cooking from seasonal produce.

Proven Impact: The Sustainable Food Places programme outlines local gains in procurement, food access and emergency responses improving resilience.

Closing thoughts

If this summer’s sunshine reminded us of nature’s generosity, it also reminded us how precarious the UK’s food system is. Yet, despite our current systems being vulnerable, there is also the possibility of positive change.

If we believe that 60% food sufficiency is too low a figure for the UK then we should take steps now to adjust this. I belive that with the right mix of integrated national strategy, local action, shifts in land use and farming practices, diet changes, and strong local agency and public engagement, the UK could turn its fields, towns, and coastlines into a model of modern food resilience — one rooted in soil health, community connection, and shared responsibility.

We already have the knowledge, technologies, and creativity to achieve this.

What’s needed now is resolve: to value local food, reward resilient farming, and see self-sufficiency not as isolation, but as a form of interdependence with nature, with neighbours, and with our future selves.