Queer Desire and Sex Work in 18th and 19th Century Edinburgh

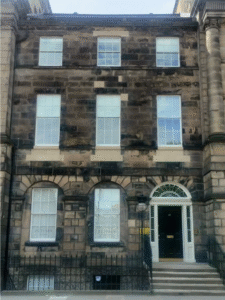

Acheson House

In the 19th century, Edinburgh had around 800 prostitutes and 200 brothels for a population of less than 150,000. Sex workers would have been a common sight on the Royal Mile, with many conducting their trade in local spirit dealers – such as the National Trust property Gladstone’s Land.

Further down the Mile on Bakehouse Close is Acheson House. This 17th century building was constructed for Sir Archibald Acheson, Secretary of State for Scotland. The family crest featuring a cockerel and trumpet is carved above the entrance. By the early 1800s, the building had been repurposed as a brothel, as the cities’ elites moved to the New Town. The house soon earned the cheeky nickname among locals: “The Cock & Strumpet”.

The Edinburgh Magdalen Asylum, founded in 1797 in the Canongate, was initially intended to be a refuge for women leaving prison. One of at least four in the city, it soon shifted to its mission of rehabilitating women trying to leave sex work. These institutions were charitable organisations, funded by church collections and private donations, established to provide so-called “fallen women” with religious and vocational instruction before placing them in domestic service.

Whilst framed as benevolent institutions, in reality the Asylums targeted the most vulnerable and isolated young women (often teenagers and pregnant women). In theory, residents were free to leave at any time, but in practice this was rarely possible.

These institutions were steeped in class hierarchy and misogyny, overwhelmingly focussing on working-class women who were presumed to be of lower moral character. They ignored the reality that sex work involved men and individuals from middle and upper-class backgrounds as well.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s family contributed to the Magdalen Asylum’s efforts and actively campaigned against prostitution, however Stevenson himself reportedly indulged in the city’s seedier pleasures during his time as a student. The brothel in Bakehouse Close was known to be his favourite haunt.

Bell’s Wynd

“Ranger’s Impartial List of Ladies of Pleasure”, published in 1775 and authored by James Tytler, served as an 18th century guidebook to Edinburgh’s sex trade – offering individual descriptions of 66 women and a fold-out map indicating where they could be found.

James Tytler was the son of a Presbyterian minister and originally trained for the ministry himself. He later gained scholarly recognition as the editor of the second edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. In 1784, he made history as the first person in Britain to ascend in a hot air balloon. He was also a close associate of Sir Walter Scott, who may have participated in some of Tytler’s more illicit pursuits.

According to Ranger’s List, Bell’s Wynd was the territory of Miss Walker and Miss Menzies. Miss Walker owned an expensive “genteel” brothel employing 8 women, while Miss Menzies worked alongside just one other woman. While Miss Walker had a house, Miss Menzies probably rented and worked out of a single room. Landlords often preferred renting to prostitutes as they could charge exorbitant rates the average day labourer could not afford.

All brothels listed were operated by women, each employing between one and nine others. Despite the stigma, prostitution did offer the potential for social mobility for those who managed to attract wealthy patrons. Of the 66 women featured, ten were either married or soon to be. There are at least two possible LGBTQ+ figures featured in the list. One goes by the alias ‘Henry’ and the other wears men’s clothing, and they were both employed at the same brothel, showing it catered to a certain audience.

Scott Monument

Functioning between 1732 and 1836, the Beggar’s Benison Club was known for its libertine practices and elaborate sexual cermonies, often with homoerotic insinuations. Originally founded in Anstruther, Fife, the club later established offshoots in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and even St. Petersburg. Its early members were mainly local merchants and minor gentry, but over time the club attracted elite men – including the future King George IV, and allegedly Sir Walter Scott.

A number of club artefacts have survived, among them a snuff box containing pubic hair, reportedly presented by George IV. The gift was said to replace an earlier ceremonial wig made from the pubic hair of King Charles II’s mistresses, traditionally worn by the club’s leader. Their motto, “May prick nor purse ne’er fail you,” encapsulated their blend of sexual and material indulgence.

Homoerotic activities ranged from phallus comparison to drinking from penis-shaped vessels and participating in group masturbation for collective inspection. When the Beggar’s Benison folded, the last £70 in club funds were used to buy books for a primary school in Fife.

Charlotte Square

In 1810, two Edinburgh school teachers sued for libel after they were accused of lesbianism, resulting in the collapse of their school. The school had been founded the previous year by Marianne Woods, her aunt Ann Woods and friend Jane Pirie.

The school was on the site of present-day Drumsheugh Gardens, and its central location and prestigious reputation attracted pupils from Edinburgh’s most influential families. Lady Helen Cumming Gordon, a widow living at the newly built 22 Charlotte Square, sent her granddaughter, Jane, to board there.

Jane was born in India to an Indian mother and Scottish father. After her father died, her paternal grandmother placed her in an apprenticeship with a Scottish milliner, before moving her to the Woods-Pirie school to receive a more ladylike education. Despite her aristocratic connections, Jane appears to have been treated harshly, likely due to both racism, and her illegitimacy.

The school housed ten boarders in two dormitories, with both teachers sharing a bed with a pupil for nighttime supervision. This arrangement was not unusual at the time. However, on Saturday 10th November 1810, Jane visited her grandmother and reported witnessing what she described as a sexual relationship between Woods and Pirie.

Seeking further confirmation, Lady Helen questioned Jane’s cousin, another pupil at the school, who affirmed the rumours. Lady Helen withdrew both girls from the school and sent letters urging other parents to do the same. The consequences were swift: nearly all pupils were removed, and the school collapsed. Woods and Pirie responded by suing Lady Helen for £10,000 in damages, alleging false and defamatory accusations that had ruined their reputations.

The case came before the Edinburgh Court of Session in Parliament Square. Jane, a key witness for the defence, testified alongside other pupils and a school servant. She maintained her claim that the teachers were sexually involved, stating that Miss Woods frequently visited Miss Pirie’s bed – where Jane also slept. The prosecution’s approach was to discredit Jane’s character, by attacking her mixed heritage, illegitimacy, and upbringing in India.

Bias extended beyond Jane’s background. At least one judge openly dismissed the possibility of sexual relations between two women, reflecting the gendered and heteronormative assumptions that underpinned much of the case. Lord Meadowbank commented that the idea of two women having sex was “equally imaginary with witchcraft, sorcery or carnal copulation with the devil”. Miss Woods and Miss Pirie eventually won the case, although they received little compensation after legal fees.

The court case inspired Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play “The Children’s Hour”, and later film starring Audrey Hepburn. Due to stigma at the time, some performances of the play altered the topic to avoid the lesbian theme. Although the film kept the theme in tact, the actual word “lesbian” was not allowed to be said on-screen. Similar racial erasure took place in the film, as Jane Cummings is presented as white.

The true story behind The Children’s Hour provides a stark contrast to the Ranger’s List and booming sex trade in Edinburgh at the time: the disbelief and censorship of a relationship between two genteel women appears to be in direct odds to the blatant nature of the Ranger’s List and clubs like the Beggar’s Benison, which did not hide the LGBTQ+ nature of their activities. It could perhaps be said that what was allowed to be spoken about in “proper” society was at direct odds with the actual desires of the population of Edinburgh, and the histories on-the-ground.

This was an excerpt from Katherine Scott and Katie Grieve’s book, “Edinburgh Historic Walks: A Summary of Hidden Histories”