Johnstone Terrace

Before the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act made schooling compulsory for children aged 5 to 13, poor families in Georgian Edinburgh had little to no access to education. This led to a rise in youth gangs, particularly in areas like Grassmarket and Canongate. On Hogmanay 1811, several gangs rioted – armed with clubs, they roamed the streets attacking bystanders. One group stormed a midnight service at the Tron Kirk. Two people, including a police officer, were killed. Several gang members were arrested; some were transported, while three – all under the age of 18 – were hanged for murder.

Church leaders concluded that education for the poor was essential to prevent further delinquency and violence. Sunday Schools were set up in every parish, though they failed to reach all children. In 1837, Rev. Thomas Guthrie, newly appointed to Greyfriar’s Kirk, opened a makeshift classroom beneath the church, offering free meals and basic lessons. His efforts led to the foundation of two more “ragged schools” nearby, on Johnstone Terrace and Ramsay Lane.

The ragged schools (so called because the children wore rags) had a unique curriculum; providing education, regular meals, clothing, industrial training and Christian instruction. Children attended 12 hours a day in summer and 11 in winter, starting at 8am with ‘ablutions’ (washing oneself) and ending at 7:15pm after supper.

Though widely supported, helping cut child imprisonment by 75%, the schools were criticised for their Protestant bias. In response to the influx of Irish Catholic immigrants in the 1840s, especially in Cowgate (dubbed “Little Ireland”), the United Industrial School was founded nearby, employing a Catholic teacher to lead worship.

St John’s Episcopal Church

In the mid-19th century, as the British Empire looked to train a class of elite Indians for roles in science, medicine, and administration across the colonies, Edinburgh University saw a growing influx of Indian students. In 1883, these students established the Indian Association – the first South Asian student society in the UK. Initially based at 11 George Square and later at 3 Potterrow, the Association championed progressive causes such as the abolition of capital punishment and was among the first university societies in Edinburgh to admit women.

Between 1927 and 1934, Indian students faced open racial discrimination when local restaurants and cafés in Edinburgh imposed a colour bar, refusing service to non-white patrons. The Indian Association led a high-profile campaign against this injustice, becoming a powerful voice for racial equality in the city.

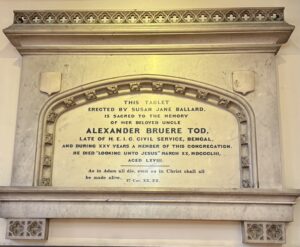

A memorial at St John’s Episcopal Church commemorates two men -Alexander Tod, a captain in the East India Company, and George Swinton, a senior colonial official who sent Indian scientific specimens to Edinburgh University. Both amassed wealth through imperial exploitation in India, highlighting the deep colonial ties that underpinned Edinburgh’s institutions.

Shandwick Place

The Edinburgh Association for the University Education of Women (EAUEW), originally the Edinburgh Ladies’ Educational Association (ELEA), campaigned from 1867 to 1892 for women’s access to higher education. Part of a broader European movement, the Association contributed evidence to a government commission, helping shape the Universities (Scotland) Act of 1889, which led to the admission of women to Scottish universities.

Though separate from the controversy around the Edinburgh Seven (Britain’s first female medical students), the ELEA offered university-level courses to women in subjects ranging from English and Mathematics to Chemistry and Bible Criticism. The lectures were given by Edinburgh University academics in a room in 15 Shandwick Place. When women were formally admitted to the University in 1892, the group shifted focus to supporting female students, providing accommodation and a library at 31 George Square. It remained active until the 1970s.

Prior to this organisation, women had rarely attended University of Edinburgh lectures, with the exception of James Barry (born Margaret Anne Bulkley). Barry graduated from Edinburgh in 1812 and served in the British Army as a medical officer, rising to the rank of Inspector General in charge of military hospitals, the second-highest medical office in the British Army. Barry had an illustrious career and performed the first recorded caesarean section by a European in Africa, in which both the mother and child survived. Barry lived as a man both in public and private (using the name James in letters to family), and their anatomy only became known to the public and military colleagues upon a post-mortem examination.

Randolph Crescent

The Stevenson sisters, Louisa and Flora, were founder members of the Edinburgh Ladies’ Educational Association (ELEA), and were prominent figures in the women’s rights movement.

Louisa’s priority was the struggle for women to be allowed medical training and to qualify as doctors: she was honorary treasurer of a committee formed to support Sophia Jex-Blake and help with legal costs in her campaign to open medical education to women. Louisa was one of the first two women elected to the Edinburgh Parochial Board (boards set up by parishes to help the poor) and was concerned particularly about improving the standard of nursing in the city poorhouse. In 1875, she and Christian Guthrie Wright founded the Edinburgh School of Cookery, with a focus on improving the diets of those in poverty. This school later became Queen Margaret University.

In 1872, the Education (Scotland) Act enabled women to serve on school boards. Flora was elected to the Edinburgh School Board in 1873, becoming one of the first women elected to a school board in the UK. She became the first woman chair of the Board and was re-elected for 33 years until her death. In 1892, Flora became an Honorary Fellow of the Educational Institute of Scotland. She was also a committee member of the United Industrial Schools of Edinburgh and ardent supporter of ragged schools.

Both sisters lived to see women attend University, although they never did so themselves – perhaps Louisa was the first founder of a modern university to not have a degree. The Stevensons were also suffragists, however passed away before they could benefit from their efforts, with the vote not given to women until over a decade after their deaths.

This was an excerpt from Katherine Scott and Katie Grieve’s book, “Edinburgh Historic Walks: A Summary of Hidden Histories”