Last year, I had the honour of giving the Doug Altman Memorial Lecture at the Peer Review Congress in Chicago. As long ago as 1994, Doug famously wrote, ‘we need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons’ (Altman, 1994). And so, I took as my theme, Does the Journal Article have a future?

Recent discussions around our preparations for the 2029 REF submission made me think again about the central role that publication plays in our work. REF have provided greater clarity that it is the institution, not individuals, who are assessed. However, it is our publications, as individuals, which make the lion’s share of the outputs being assessed. The ongoing discussions about whether the University should consider renewing the various deals we have with publishers such as Elsevier, or consider these to represent poor value for money, are a further reason to think about this.

Scientific publishing is a hugely profitable industry. Ever since Robert Maxwell grew Pergamon Press after the second war, printing scientific articles has also been a licence to print money (Buranyi, 2017). [My contemporaries may remember Maxwell as the ‘saviour’ of the 1973 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games – which ended up losing £4m and cost the City of Edinburgh Council £500,000. His daughter, Ghislane, has also been in the news recently]. Mark Neff, an associate professor in environmental studies as Western Washington University, has written:

Between 1959 and 1965, Pergamon grew from 40 titles to 150. Whereas scientific norms at the time viewed scientific publishing as a public good that should not be subject to profit motives, Maxwell understood that scientific publishing was a market unlike others because there was an almost ceaseless growth of demand, and free labor. Scientists would pressure their institutional libraries to secure access to any serious journal publishing work relevant to their own. If the generous postwar government funding of science was the push that fueled rapid growth of science, the profit-seeking appetite of publishers was the pull. (Neff, 2020)

To unpick this a little, the ‘almost ceaseless growth in demand’ is driven, in large part, by our need as researchers to publish, so that we can demonstrate to our employers, our funders and our peers what we have been doing, and how great we are. Where these evaluations are done by people who can’t, or wont, invest the time and expertise critically to evaluate the originality, significance and rigour of a publication, they fall back to using proxy measures like the journal in which the work was published. This is a very poor measure of anything, and also establishes a role for scientific journals as the gatekeepers to our careers.

‘Free labor’ (sic) is Mark’s nice way of saying that just about everything of value in scientific publishing is either given or paid for by the academic community. We plan the research, do the work, write it up, format it in the required style, and submit it for publication. Then, other researchers play the role of (usually unpaid) academic editors, deciding whether it should go to review, and by whom. Other researchers do the peer review, then it’s off to get typeset, often with very little quality control. Then we pay for the privilege of having our work published; and other researchers pay (directly, or through their institutions), for the privilege of reading the work. The annual cost to UoE of these ‘read and publish’ deals is around £3.8m.

So how profitable is scientific publishing? In 2024 Wiley reported profits of $331m, Springer Nature $489m, and Elsevier a whopping $1.498bn, each with profit margins of over 30%, more than either Apple or Amazon (Beigel et al, 2025); and built, as outlined above, largely on the free labour of the academic community.

Of course, as ‘public’ researchers (funded by taxpayers or charities rather than for-profit companies) we usually want our research findings to be disseminated and read widely, so that others can build on or challenge our work, and so that our contribution can be appropriately recognised. Are there other vehicles for this, beyond the traditional journal article? The days when papers actually required paper are long gone, and electronic distribution is much more efficient – and cheaper – than printing and posting to subscribers and libraries.

Where Journals might add value compared with, for example, preprint servers is firstly through improved dissemination – reaching your desired audience – and secondly as an indicator of the quality, usefulness and provenance of the work. Is this worth reading? Is this researcher any good? Electronic searching means we can identify articles from a huge range of journals, rather than the few for which we receive Table of Contents alerts, so the dissemination gains are marginal.

As a quality indicator, peer review can lead to substantial improvements between submission and publication, but this is not always so. There are many egregious examples of wonky research published in journals of very high impact (see, for instance, Obokata et al, 2014) and this means that every research user, everyone who might plan their future work on the basis of what is in the literature, needs to be able to do their own critical appraisal, their own peer review. Like assessing researchers, there is no alternative to reading the freaking paper, wherever it was published!

That critical appraisal is of course greatly facilitated if, as research users, we have access to the data, the code, the methods, and if we know the extent to which these were established in advance. I’m not saying we should always check every detail, but we should be able to do ‘spot checks’ to increase our confidence in the findings. That’s why I’m such a strong advocate of open research – I need to know these things to make a judgement about what I can trust. With apologies to my peers, there are too many contemporary examples of poorly conducted or simply fraudulent research for me to trust if I am not able to verify.

For peer review to add value, it needs to ensure quality all, or nearly all, of the time. That is not currently the case, if indeed it has ever been. There is also the question of the costs of conventional publishing in delays to publication. Several years ago we audited the publication pathway for animal research in Edinburgh, interested in the times from the work being conducted, submitted for publication, and then published. We only had details of the submission date for the final journal of publication, so our analysis did not take into account any previous submissions to other journals. We found a median interval between the work being initiated and being published of 987 days; of which 235 days, or 24%, was between submission and publication. We hope our work has value; and value declines, or depreciates, over time. In fact, the New Zealand Tax Office has a published rate for the depreciation of scientific publications – the rate at which companies holding such assets can write off the value – of 20% per year. Without wishing to over-stretch the application of financial accounting principles here, those 235 days equate to a loss of value in our published work of 12%, compared with dissemination through preprint servers.

It is I think instructive to think a little more about the value of information we produce. Moody and Law (1999) have articulated 7 laws on the value of information as a public good:

1. Information Is (Infinitely) Shareable

I can send my information to anyone, and they can share it onwards. For several years I received a daily notification of the lunch menu in a hospital where I had previously worked, so infinite sharing of information is not always a good thing.

2. The Value of Information Increases With Use

Since the costs of re-use are trivially small, the costs of production are shared between more users, and the unit cost falls; and the re-use creates a further information asset, which increases value

3. Information is Perishable

If you don’t look after your information, it will end up on a USB stick or in a file format that you can no longer access

4. The Value of Information Increases With Accuracy

This is self evident, and again makes the case for the sharing of methods, data, code that might give greater confidence in the accuracy of the information.

5. The Value of Information Increases When Combined With Other Information

My day job is in evidence synthesis (see, for instance, AD-SOLES), so I’m bound to agree wholeheartedly with this.

6. More Is Not Necessarily Better

We’re back to Doug Altman here!

7. Information is not Depletable

Your using my information does not reduce the amount of information I have.

Pulling this all together, I hope I’ve been able to convince you that the quality, the original, the significance and the rigour of our research is much (much) more important than the venue in which it ends up being published; that the internet has effectively cut the ties that bound us to the traditional publishing model; that scientific publishers are desperately struggling to find new ways of making money from us, while seeking to convince us that the journal article is not dead; and to persuade you of the benefits of pre-registration, preprint servers, and publishing your data and code alongside your research findings.

Malcolm MacLeod

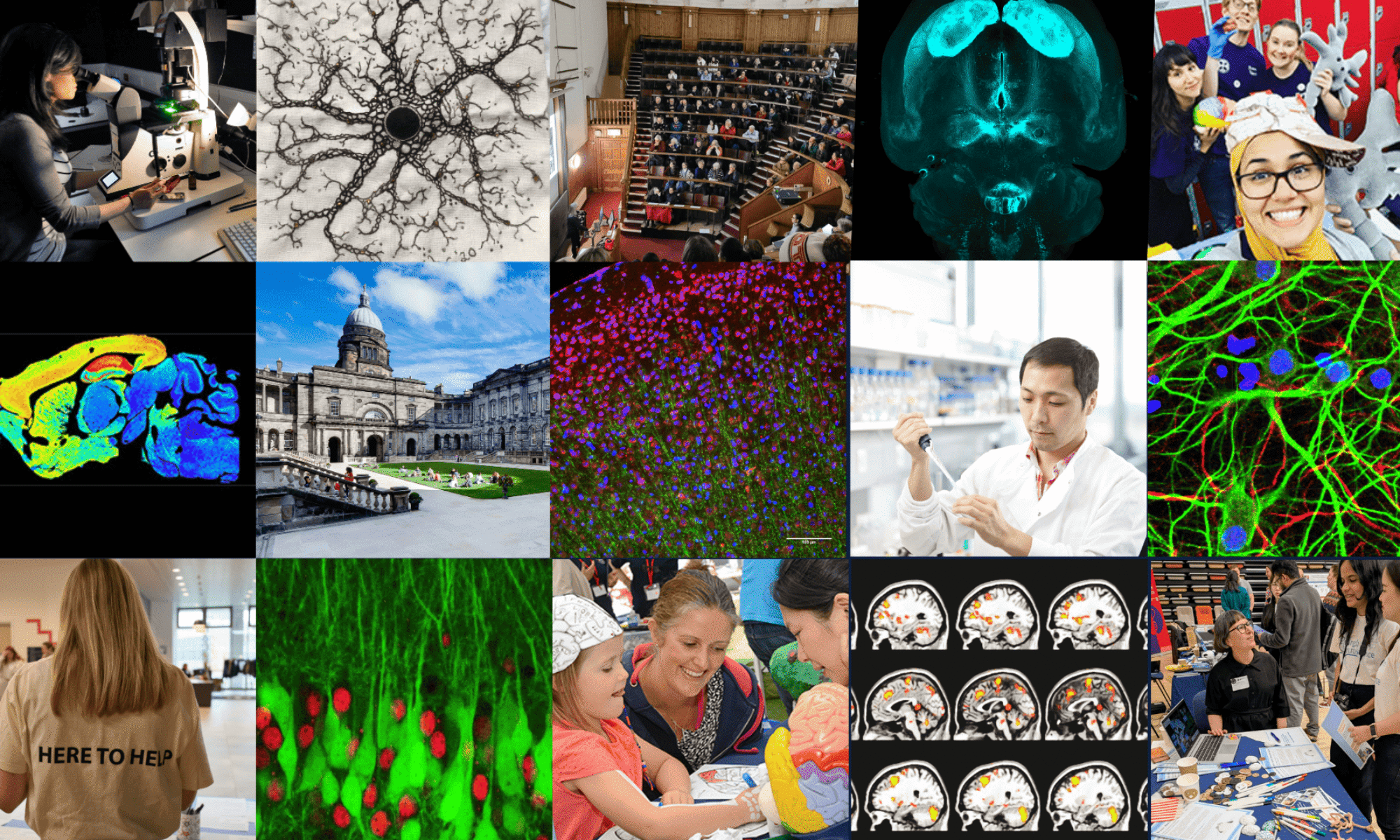

Professor of Neurology and Translational Neuroscience; Co-Director, Edinburgh Neuroscience

*Note: Edinburgh Neuroscience is coordinating the University’s submission to REF2029 Unit of Assessment 4, Psychology, Psychiatry and Neuroscience.

References:

Altman, D.G. (1994) The scandal of poor medical research, British Medical Journal, 308:283; 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.283

Beigel, F., Brockington, D., Crosetto, P., Derrick, G, Fyfe, A., Barreiro, P.G., Hanson, M.A., Haustein, S., Lariviere, V., Noe, C., Pinfield, S. & Wilsdon, J. (2025) The Drain of Scientific Publishing. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.04820

Buranyi, S. (2017, 27 June) Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science? Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science

Moody, D. & Walsh, P. (1999, 23-25 June) Measuring The Value Of Information: An Asset Valuation Approach, paper presented at the Seventh European Conference on Information Systems [Conference presentation]. Seventh European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS’99), Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark. Download PDF

Neff, M.W. (2020) How Academic Science Gave Its Soul to the Publishing Industry, Issues in Science and Technology 36(2), 35–43. https://issues.org/how-academic-science-gave-its-soul-to-the-publishing-industry/

Obokata, H., Wakayama, T., Sasai, Y., Kojima, K., Vacanti, M.P., Niwa, H., Yamato, M. & Vacanti, C.A. (2014) Retraction Note: Stimulus-triggered fate conversion of somatic cells into pluripotency, Nature, 505; 10.1038/nature12968