1. My Role and Vision

As the sole documentary creator for this project, I was independently responsible for every stage—from initial concept development and content planning to filming and editing.

My goal was not simply to “document” the process, but to present a complete and emotionally resonant journey—from the early ideation of our installation to its final realization—while authentically highlighting the efforts of each team member and capturing the audience’s real-time interaction with the work.

The documentary structure deliberately avoids a linear narrative. Instead, it revolves around three thematic pillars: project concept, team contributions, and audience engagement. Each section is carefully designed to balance information delivery with emotional rhythm, aiming to evoke a deeper viewer connection with the installation.

2. Documentary Structure Overview

Part 1: Project Concept & Creation Process

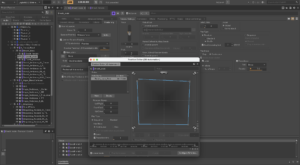

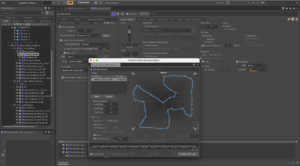

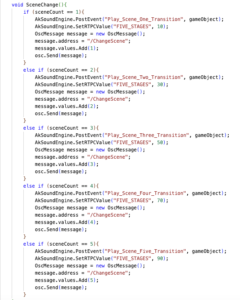

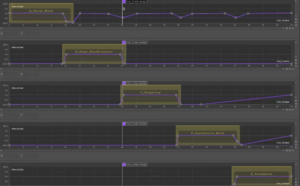

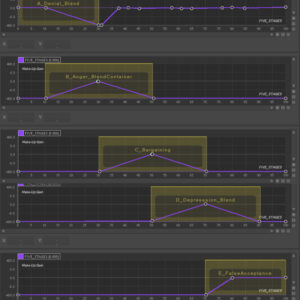

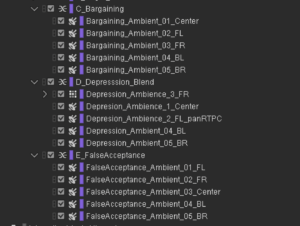

The first section introduces the inspiration and objectives behind our project through a narrated voiceover. It explains how we translated the Kübler-Ross model of the “Five Stages of Grief” into emotional, visual, and auditory forms, ultimately creating an interactive installation.

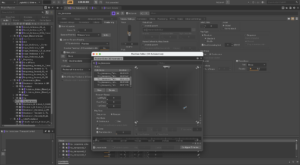

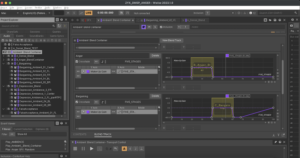

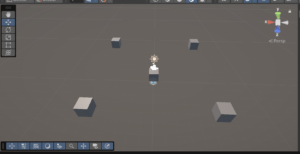

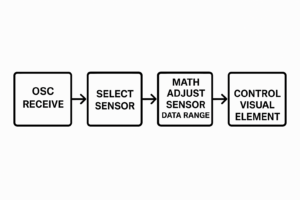

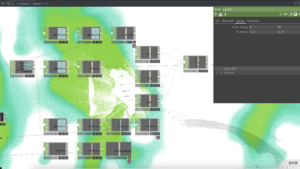

The visuals match this narration with real work footage, from our initial research and emotional analysis to the preparation and testing of the sound, visual, and technical modules. Through this material, I wanted the audience to not only understand our creative and technical paths but also feel the team’s focus, experimentation, and iterative process.

Part 2: Team Member Interviews & Contributions

For the second section, I conducted concise yet in-depth interviews with each team member. They discussed their specific roles, challenges faced, problem-solving approaches, and personal reflections.

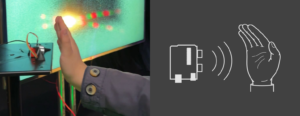

To enhance viewer understanding, each interview is seamlessly integrated with real footage of the members working—whether calibrating sensors, designing visuals, or assembling components. This pairing not only improves information clarity but also vividly portrays the team’s collaborative efforts and dedication.

Part 3: Exhibition Day & Audience Interaction

The final part captures the live exhibition, from setup to operation and real-time audience engagement. I filmed audience reactions—their surprise, curiosity, and feedback from peers and instructors alike.

Compared to the first two sections, this part adopts a more open and emotional visual rhythm. I preserved many moments of “body-emotion” interaction between visitors and the installation, ending the documentary on a natural, uplifting note that highlights the genuine resonance our work created.

3. Filming Process & Real-World Challenges

Throughout the filming phase, I independently captured all video materials needed for the documentary. To ensure consistency in quality and style, I made weekly trips to the university’s equipment library, renting cameras and tripods as needed. I carefully selected lenses and gear based on the specific shooting tasks, striving to maximize visual outcomes within the limits of available resources.

Shooting Strategies & Camera Planning

Following the documentary’s three-act structure, I wrote a detailed editing script and pre-planned the shooting content and camera strategies:

-

During Production & Preparation:

I used lenses with medium depth of field to authentically capture team members working on device operation, sensor calibration, and audiovisual testing over three weeks. To highlight fine details, I switched to macro lenses when necessary. -

During Interviews:

I used prime lenses with deep focus settings, ensuring the interviewee’s face was crisp while backgrounds remained soft and understated, creating an atmosphere of focus and calm. Lighting and composition were carefully adjusted for each interview to maintain a consistent, professional look. -

During the Exhibition:

I set up a stationary camera to shoot wide-angle footage, capturing the full spatial setup and operation of the installation. For dynamic audience interactions, I used handheld lightweight equipment, allowing me to move flexibly through the crowd and catch real-time reactions and expressions.

On-Site Challenges & Adaptive Solutions

Filming within the active work environment posed challenges such as time constraints, limited space, and difficulty coordinating repeat shots. I adopted the following strategies:

-

Quick Setup and Silent Filming:

To avoid disrupting the team’s work, I adapted quickly and kept filming as unobtrusive as possible. -

Interview Guidance and Emotional Engagement:

I briefed interviewees beforehand to encourage natural, genuine responses. -

Dynamic Shooting Adjustments on Exhibition Day:

Given the noisy, crowded environment, I frequently shifted angles, used stabilization gear, and captured ambient sounds to maintain audio-visual quality. -

Supplementary Detail Shots:

I filmed close-ups of screens, device components, and the operation of Kinect sensors for later use as visual transitions during editing.

Additionally, I manually adjusted exposure and white balance on-site to ensure a unified, layered look across different shooting conditions.

4. Post-Production: Editing & Fine-Tuning

In the editing phase, I went beyond technical assembly—I curated the content structure, controlled the pacing, and refined the visual storytelling. Multiple key sections underwent repeated revisions to ensure smooth rhythm and emotional coherence.

Editing Techniques & Highlights

-

Interview Editing:

Many interviews included pauses, repeated phrases, or inconsistent speech rhythms. I used seamless editing techniques to splice together complete sentences while overlaying B-roll footage (members at work) to naturally hide cuts and enrich visual storytelling. -

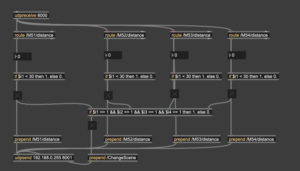

Precise Audio-Visual Synchronization:

For narrated explanations, I matched every line of voiceover with exact visual counterparts. For instance, during the line “We use four ultrasonic sensors to control emotional transitions,” the footage cuts to a close-up of the sensors’ wiring and live feedback. Fine-tuning these alignments helped maintain clarity and controlled pacing. -

Pacing and Dynamic Energy:

While documenting exhibition setup, I fixed a camera to capture the team’s real-time workflow. I later accelerated this footage during editing to energize the rhythm, creating a vivid sense of efficient collaboration and adding a sense of time progression to the documentary opening.

Key Challenges & Solutions

-

Massive Footage & Narrative Overload:

The large volume and diversity of footage initially caused an overloaded rough cut. To solve this, I restructured the material into three clear categories: Process, Concepts, and Outcomes. I rebuilt the timeline at least three times until achieving logical clarity and natural flow. -

Voiceover Script Refinement:

Balancing technical accuracy and accessible storytelling was difficult. I wrote three versions of the script, repeatedly recorded and reviewed them, ultimately settling on a clear, professional, and engaging narration. -

Authentic Sound Presentation:

Following feedback from instructors, I removed background music in certain scenes to highlight the installation’s natural ambient sounds. I also included an independent segment showcasing our sound design achievements.

Final Reflection

The documentary’s creation process—marked by iterative revisions and frame-by-frame refinements—tested my patience and precision to the fullest. I never settled for mere completion; my aim was always to deliver a visual narrative that powerfully, honestly, and emotionally conveyed our team’s creativity and collaborative spirit.

Through this film, I hope viewers can not only understand our technical achievements but also feel the passion and emotion that brought our interactive installation to life.