For the final phase of the project, I focused on refining and scaling our distance sensing setup. The goal was to clean up noisy sensor data, set a distance cap, connect everything to a shared network, and build a centralized system for routing and processing OSC messages in real time.

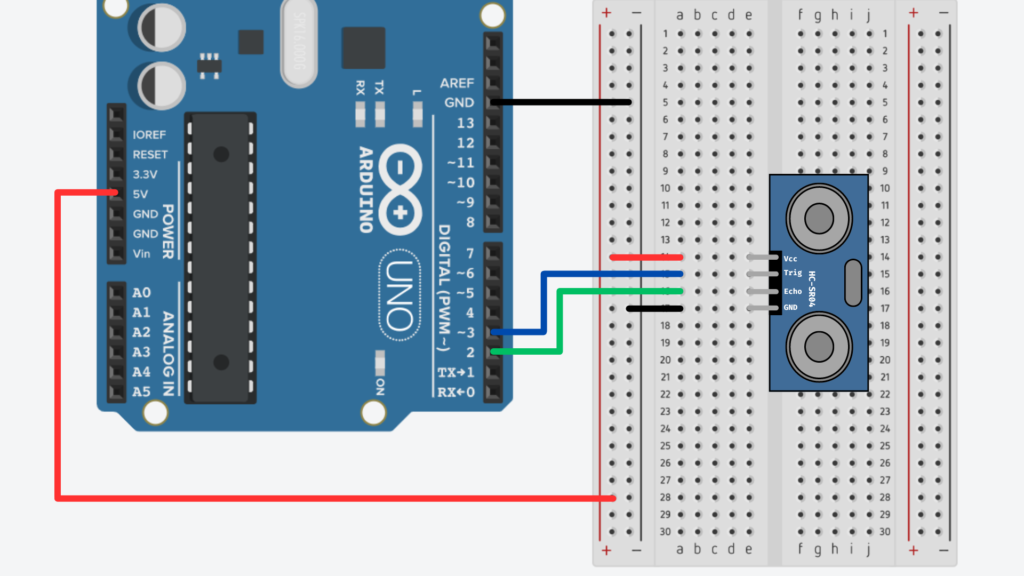

Hardware Refinement

I tested several M5StickC-Plus boards and HC-SR04 sensors, comparing consistency across units. Some sensors fluctuated too much or lost accuracy at mid-range distances. I ended up choosing the four most stable ones.

Each M5Stick was flashed with the same code, but I updated the OSC address string at the top so each sensor would send data to a different address:

String address = "/M55/distance";

Network Setup: Leo’s Router

Instead of using Joe’s mobile hotspot, I switched over to Leo’s router, which provided a more reliable connection. This was important for minimizing packet drops and keeping multiple sensors running smoothly.

const char *ssid = "LeoWiFi"; const char *password = "Presence";

The M5Sticks all send their messages to:

const IPAddress outIp(192, 168, 0, 255); const unsigned int outPort = 8000;

Distance Measurement and Capping

The sensor code still uses the familiar trigPin/echoPin setup. After triggering and timing the ultrasonic pulse, I added a cap to prevent noisy long-range readings:

float cm = (duration * 0.034) / 2.0; if (cm > MAX_DISTANCE) { cm = MAX_DISTANCE; }

Averaging the Distance Values

To smooth out the data, I used a rolling average over the last 10 readings. Each new value is added to a buffer, and the average is recalculated every loop.

#define NUM_SAMPLES 10 float distanceBuffer[NUM_SAMPLES] = {0}; distanceBuffer[bufferIndex] = cm; bufferIndex = (bufferIndex + 1) % NUM_SAMPLES; float sum = 0.0; for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SAMPLES; i++) { sum += distanceBuffer[i]; } float avgDistance = sum / NUM_SAMPLES;

Normalization for OSC Output

The averaged distance is normalized to a 0–100% scale so it’s easier to use for modulating audio or visual parameters:

float normalizedDistance = (avgDistance / MAX_DISTANCE) * 100.0;

This gives us a value like “23.4” instead of “78 cm”—much easier to use directly in Unity or TouchDesigner.

Sending the OSC Message

Once the data is ready, the M5Stick sends it as an OSC message using the CNMAT OSC library:

OSCMessage msg(address.c_str()); msg.add(normalizedDistance); udp.beginPacket(outIp, outPort); msg.send(udp); udp.endPacket(); msg.empty();

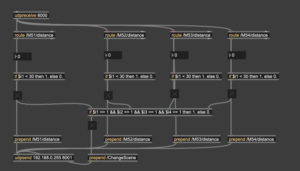

Centralized Processing in Max

Rather than having each sensor talk directly to Unity or TouchDesigner, we built a central Max patch to receive and clean all OSC data.

Here’s what the patch does:

- Uses udpreceive to listen for all messages on port 8000

- Routes each message by OSC address (/M51/distance, /M52/distance, etc.)

- Compares each value to a threshold (e.g., < 30) using if objects

- Sends a 1 or 0 depending on whether someone is near that sensor

- If all sensors are triggered at once, it sends a /ChangeScene message to both Unity and TouchDesigner on port 8001

This setup keeps the sensor logic modular and centralized—easy to debug, scale, and modify. We only need to change one patch to update the interaction logic for the entire system.

Final Testing

We tested everything together, and it worked: scene and audio changes were successfully triggered in Unity, responding to movement in front of the sensors. I also captured a video of the audio modulating based on proximity.

This system is now:

- Scalable (thanks to Wi-Fi and OSC)

- Cleanly routed (through MAX)

- Responsive (with smoothed, normalized data)

It’s exciting to see everything running reliably after so many small iterations.