Author: s1850658

Wwise Project Folder Link

Can be downloaded from this link as a zipped folder:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1nMPEhFXg1p5RReNgBzwlehbknifaAwi8?usp=share_link

Personal Reflection – David Mainland

Overall, I was incredibly happy with how the project turned out and I had a lot of fun during the process. Everyone was very nice and everyone chipped in equally to create the final product.

On the sound side of things, I am generally very pleased with the end result. I do think however, that there are some things I personally could have done, or done better, to make the final product a little more polished.

Giving more consideration to the spacialisation of sounds is one thing I definitely think I should have done, as most sounds aren’t spacialised. I think it really could have added a lot to the player’s sense of space within the world, and could have been a great opportunity for some interesting and creative sound design.

Secondly, I feel as though the hierarchy I made initially was not suited to the more linear nature that the experience ended up having. I think this was caused by two factors. Firstly, my previous experience using Wwise in Interactive Sound Environments, and perhaps not corresponding with the design team as much as I should have.

Overall though, I am very happy with the project. I want to thank everyone in the group for working so hard and making it a really fun project to be a part of. I’d also like to thank Leo for all of his help. Regardless of whether it was early in the morning or later on in the evening, weekday or weekend, he was always just a Teams message away.

My Role in the Project – s1850658

My Role in the Project – s1850658

Preparing Audio for the Wwise Project

Most of the sounds that went into the final Wwise project were first placed into a Logic project file, where they were edited and processed. By the end of the project, the Logic file contained around 150 tracks.

Because the approach in Wwise used mainly random containers set to continuous, the editing process mainly consisted of finding the parts of the raw audio that I wanted to use, slicing it up into sections, adding crossfades and then bouncing those individual sections as separate audio files.

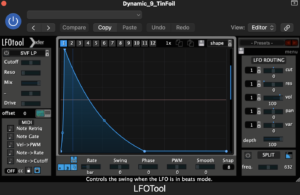

For processing, Logic’s stock gain plugin, DMG Audio’s Equillibrium EQ plugin and Waves’ NS1 noise reduction plugin were the main tools I used – and almost every sound was processed using these three plugins. Some sounds however, needed a bit more. In addition to these plugins, I also used Logic’s stock pitch shifter and stock distortion, Aberrant DSP’s Digitalis and Shapeshifter, and Xfer Records’ LFOTool.

The pitch shifter and LFOTool were used for the animal footstep sounds. For the main piece of audio, I used a recording from the foley session of someone crushing the petals of a month-old bouquet of roses. This then went through LFOTool to create the dynamic contour of a footstep. I did this several times, varying the envelope interval to get some longer and shorter footstep sounds. The pitch shifter, in combination with some EQ, was used to create footstep sounds for small, medium and large-sized animals.

Digitalis was used for its repeater, which repeats the audio sent in at set intervals, and for a set number of beats. This was used when I wanted particular pieces of audio to sound busier, such as the bee sounds. The mix control would be set to around 50% so that the dry audio could still be heard clearly. To add some variety I took advantage of Digitalis’ feature that allows you to sequence the value of parameters. I sequenced the repeater rhythm and duration.

The distortion and Shapeshifter were used to add a bit more bite and impact to more intense sounds, namely some of the fire sounds. In these instances, Shapeshifter was used less as a compressor, but instead to saturate the sounds a little. I did however, use Shapeshifter on some of the rain sounds, as along with making it sound a bit more intense, it had the added benefit of giving the transients a longer tail – which I thought better suited a rain sound.

Wwise Implementation

Creative Approach

Upon seeing the environment that the other group members had created for the first time, I was very impressed. With the world that had been created being as beautiful as it was, I felt as though the soundscape had to achieve the same level of detail and richness.

I also wanted the soundscape to extend beyond the player’s view, giving the player context for the environment and really selling the idea that this forest was teeming with life, both seen and unseen – but always heard. Examples of this in the final build are things like the grass and leaves rustling in the wind, and the distant sounds of animal footsteps.

Events

Events are the main method used to control sound in the project, and thus the Wwise project contains quite a lot of them. Based on the storyboard created by another group member, we had a pretty good idea of what sounds would be present during the various stages of the experience. Furthermore, the main C# script used coroutines to represent each ‘scene’ of the experience, which worked very well with the Wwise implementation, as we could trigger stop and start events and adjust RTPCS in these coroutines.

RTPCs

RTPCs were used when sounds still needed to be present when moving from one scene to another, but an aspect of said sounds needed to be changed. The most notable example of this relates to the player’s elevation. Sounds that are closer to the ground become quieter and have filtering applied as the player moves up, and conversely sounds that are higher up or further in the distance become louder, as the player’s view encompasses more of the forest.

Containers

The Wwise hierarchy makes heavy use of blend and random containers. Blend containers are used both for organisation of different parts of the soundscape into sections (environmental sounds, weather etc), and for more complex sounds, which are made using random containers nested inside the blend container. This allows for more control over of individual parts that make up the sound as a whole. Random containers are used in three different ways: Longer sounds play continuously with an xfade transition, incidental sounds use a trigger rate transition, and some sounds use an xfade transition, but have silent audio files included in the container, to help break things up and to add some variety to how long the sound will be heard for each time.

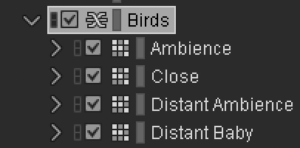

Container Example

The blend container for the bird sounds serves as an effective example of how these different applications of random containers work in context. Within the “Birds” blend container are four random containers: “Ambience”, “Close”, “Distant Ambience and “Distant Baby”. “Ambience” just uses a simple xfade transition. “Close” also uses an xfade transition is made up of shorter sounds, along with several silent audio files ranging from 2-10 seconds. “Distant Ambience” is made up of longer sounds than also use an xfade transition. In this track, I deliberately left in some of the non-bird sounds to give the birdsong some context in terms of distance, and to add to the overall soundscape. “Distant Baby” uses a random container with a trigger rate that varies by a few seconds each time. In combination, these different techniques come together to make a very full and vibrant part of the soundscape.

Reflections on Wwise Implementation

Because of the lack of player movement, when initially creating the hierarchy for the Wwise project, I focused heavily on creating a rich soundscape that would surround the player. Because of this, I perhaps did not give enough consideration to the spacialisation of sounds. The one strong example of spacialisation is the bird that flies around the player’s head throughout the experience.

The project became more linear and cinematic as it progressed. Given my previous experience working in Wwise, and the ideas during the earlier stages of the project, the implementation was created in a way that may have suited something more interactive. In retrospect, perhaps more work on RTPCs and more attention to detail regarding certain narrative set pieces could have gone a long way.

Gathering Foley Materials

Ahead of our foley session, I decided to go and gather some things. During a meeting with our tutor, he said that sometimes the real thing is best when it comes to recording foley sounds. With this in mind, I decided to travel to the forest near Blackford Hill. In some small bin liners, I collected some mulch, soil, dry dead leaves, and fresh ivy leaves. These proved to be very useful during the foley session.

Collaboration and Organisation

Since I had the job of putting together the Wwise project and creating the hierarchy, I was put in a unique position. When making the hierarchy, I was consistently referring back to the storyboard and making notes as to what sounds would be needed during each scene, and how audible they would be. This meant that when the time came to start recording and creating audio assets, I had a very clear idea of what we already had, and what else we still needed to do. This meant that at several points, I was able to take the initiative; making checklists and written summaries of the planned sound content in each scene and sharing these with the rest of the sound team. This allowed for work to be delegated and divided equally among members, and I believe this helped to facilitate collaboration between group members.

Sound Design – Storyboard Cues

Sound Design – Storyboard Cues

Following the final storyboard being shared with the group and posted on the blog, I have adapted the ideas discussed in my previous post in accordance with the storyboard. Upon reading the storyboard, I decided that it would be a good idea to compose this document, and for it to serve as a plan for the soundscape of each cue/stage in the storyboard. It marks a slight change in approach to the overall structure of the sounds. It takes a more linear and rigid approach that more closely follows the cues in the storyboard – rather than thinking of it more fluidly, as I did in the previous post. Having a solid idea of what each stage needs and how it should sound I believe will prove very useful when it comes to deciding what sounds are needed for the project, gathering and organising them, and as something to refer back to when crafting the soundscape in Wwise.

1 – The seeds are in the soil, and the player sees darkness.

The sound in this stage is perhaps the most important stage in terms of sound. Not only is it the very first stage that will be experienced by the player, but it is also the only stage where the player is not given anything visual to direct their focus towards. The context must instead be given to the player by what they can hear. Under the soil, the player will be able to hear the muffled sounds of wind, and the rain hitting the ground above them, the sounds of other plants nearby growing, the sound of insects and worms moving in the soil around them. As the player is underground, the sound that will be most present will be the insects and worms. The other sounds are happening above the soil, so they will need to sound a little more distant and muffled. The main aims of the soundscape in this stage are to give the player something to latch on to, to provide some context of where they are and the environment around them, and through achieving these, give the player a positive first impression of the experience.

2 – After the rain, the seed break through the soil and the player can see a light, as well as the soil around them, player can see the sky and some trees.

The second stage is also a very important moment when it comes to sound. It marks the player’s first proper introduction to the environment above-ground. The soundscape in this stage will start to open up and flourish, much like the seed that the player is experiencing the world through. The player finally sees the world, and the soundscape needs to reflect this new place the player now finds themselves in. Sounds that were muffled and distant begin to move closer to the player in this stage, and new sounds that were unable to reach the player in the previous stage are now audible, such as the sound of grass and leaves blowing in the wind and a cacophony of birdsong.

3 – The seeds turn into saplings and see the big trees around them.

As the seed grows into a sapling, the soundscape continues to open up and encompass more of the forest around the player. Birds can be heard more clearly, including the flapping of their wings as they pass by. The wind is now also heard whooshing through the trees, instead of just the sounds of the grass and leaves being blown around.

4 – The sapling is gradually growing taller and the player can see flowers, mushrooms and other plants around it.

In this stage, the player now begins to see much more of the plant life that surrounds them close to the ground. The presence of flowers and mushrooms, while not typically sources of sound, I feel should still be represented sonically in some way. The sounds of insects that live above ground are also now present in the soundscape, such as bees, wasps and other winged insects.

5 – Players can see some animals running around

Following the introduction of flowers and mushrooms, as well as the introduction of winged insects to the soundscape, the player is then introduced to the mammals that inhabit the forest. These could be animals like rabbits, foxes, deer, squirrels, and frogs. I am aware that terrestrial animals are currently being modelled, and that considering the scope of the project, it is likely only a select few will be visible to the player. However, at this stage the player’s view of the forest is confined to a reasonably small area, which leaves room for the soundscape to give sound to animals that are not visible to the player, to help create a sonic atmosphere suitable for a forest that is full of life. The soundscape can suggest things beyond what the player is able to see during this stage. For the animals that are visible, the sounds of their footsteps on the grass and leaves will be heard, and there will need to be a good deal of variety in these to match the size and weight of the particular animal in question.

6 – The small tree gradually grows into a large tree, looking at the surrounding landscape from a top view.

As the player grows to a height where the environment is seen from a near bird’s eye view, the sounds of the forest take on a different nature, that is appropriate to the newfound heights the tree has reached. The environmental sounds, while still very much present, become more distant, as the tree’s growth moves the player’s perspective further and further from the ground. The wind sounds will also take on a different character.

7 – The player can see small animals on the trunks of the surrounding trees, e.g. pine trees,birds.

In this stage, the player’s view now includes the leaves and branches of taller trees. This is the first time that the player will be able to see and hear the sounds of leaves that are not on the ground, but are part of other trees – at least this closely. The sounds of animals on the branches of these other trees can now be heard.

8 – The tree grows taller and taller, becoming the largest tree in the forest, overlooking the whole forest

This stage marks the peak in the height of the tree, as well as the peak in how much of the environment the player can see. Just as the player overlooks the entire forest, they should also be able to hear the entire forest. The growth of the tree throughout the previous stages has all culminated in this moment, and the scope of the soundscape should serve to reflect this.

9 – At night, the forest caught fire. The trees were in flames.

This stage in the story represents an incredible shift in the soundscape. The tree has caught fire and is now burning down. The sounds of the fire will need to be intense and feel very close and immediate to the player.

10 – The tree was consumed by fire and plunged into darkness; it rained and doused the fire

Following the destruction of the tree and many of its surrounding neighbours, rain begins to fall that extinguishes the fire, an event that demands quite an intense accompanying soundscape.

11 – Large trees transfer nutrients to other trees through the Wood Wide Web before they die out completely.

As the nutrients from the dying tree the player has been inhabiting transfers through its roots to smaller trees in the surrounding area, synthesised sounds will be heard, that represent the final act of the tree – providing nutrients so that another tree may take its place. The sounds of the nutrients flowing will begin very close to the player and become more distant and spacialized as they travel underground through the forest.

12 – A small tree by a lake gets the nutrients of a large tree to grow fast.

During the final stage, the player is no longer inhabiting a particular tree, but is instead watching as the final act of the tree breathes new life into the forest following the blaze, with soft music accompanying this renewal.

Some Brief Ideas for the Overall Structure of Sound for the Project

The following is some of my general ideas for how sound could adapt and change in response to changes in the environment. This was written before the updated storyboard was shared with the group, so ideas from the post below will need to be adapted and altered to fit – it was more of a brainstorming session regardless.

Based on the idea for the project, there are three different aspects of gameplay that will change the characteristics of the ambient sounds that are heard throughout the experience. These are: growth stage (1-3), day/night (1 or 2), and season (1-4). This creates 24 possible states that the ambient sounds can be in at any given time, through a combination of these environmental characteristics. The ambient sounds heard will be controlled using states in Wwise. For instance, the different stages of these characteristics could affect the ambient sounds like this:

- Growth Stage

- Stage 1

- Sounds that occur closer to the ground (such as insects, or flowing water) are louder and are the most present

- Stage 2

- Sounds that occur closer to the ground fade slightly and sounds that occur higher up (such as birds, or the wind) begin to be heard

- Stage 3

- Sounds that occur close to the ground fade even more and the higher up sounds take centre stage

- Day/Night

- Day

- Animals that are diurnal can be heard

- Night

- Animals that are nocturnal can be heard

- Season

- Spring

- As flowers bloom, the sounds of insects such as bees and wasps are present

- Rain and wind are present, but are sporadic and not very intense

- Summer

- The weather is at its warmest and calmest

- Autumn

- Any animal movement sounds have an extra layer, as the animals may be treading on fallen leaves or twigs from surrounding trees

- Rain and wind are present, but are sporadic and not very intense

- The sound of the wind on the trees has a different character, and the leaves on the ground are dead and dry

- Winter

- The sound of water becomes less noticeable, as much of it begins to freeze

- The weather is at its worst and most intense

- Snow/rain and wind happen often and are more intense than the other seasons

- Spring

- Day

- Stage 1

The sounds of the tree growing should also reflect the characteristics of the environment. For example, as the tree grows larger, the sounds of it growing should have more low frequencies, as the tree is bigger. Perhaps in autumn and spring – since the tree is drier than in the spring and the summer – the growth sounds could be more crunchy and dry sounding?

I also had the idea that any music that the game has can also follow this pattern. Perhaps the music could start very sparse in terms of instrumentation, and then fill out as the growth stages progress. A good example of this is the hub in Super Mario Galaxy – as the player progresses through the game and more areas of the hub are revealed, the music for this area becomes much grander (Mario Galaxy Comet Observatory 1-3). There are definitely ways of representing the other environmental characteristics of gameplay through the music. Perhaps a different piece of music for each season, or depending on whether it’s day or night? Or even a change in the instrument playing the lead melody? These changes don’t need to be drastic – as there is some clear variation based on these environmental changes.

Sounds that have a clear visual source will definitely need spacialization, but perhaps sounds that don’t have a clear source that the player can be mono. Or perhaps it could lead to some interesting results if these unseen sounds were spacialized – even just some of them.

Overall, the environment and the changes in it that happen throughout the experience have a lot of potential for creating a lot of variety in the sounds heard by the player. I’m feeling quite optimistic about all the challenges this could present, as I believe it is a wonderful creative opportunity for everyone working on sound for the project.