Video Link:

https://media.ed.ac.uk/media/DMSP+Vedio/1_nekq0tsr

Project Link:

Sound design:

Sound Recording:

Visual Design:

Video Link:

https://media.ed.ac.uk/media/DMSP+Vedio/1_nekq0tsr

Project Link:

Sound design:

Sound Recording:

Visual Design:

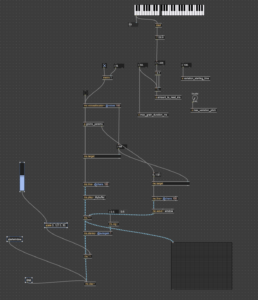

For this project, I wanted to create a sound environment that feels alive — something that responds to the presence and actions of people around it. Instead of just playing back fixed audio, I built a system in Max/MSP that allows sound to shift, react, and evolve based on how the audience interacts with it.

The idea was to make the installation sensitive — to motion, to voice, to touch. I used a combination of tools: a webcam to detect movement, microphones to pick up sound, and an Xbox controller for direct user input. All of these signals get translated into audio changes in real time, either directly in Max or by sending data to Logic Pro for further processing via plugins.

In this blog, I’ll break down how each part of the Max patch works — from motion-controlled volume to microphone-triggered delay effects — and how everything ties together into a responsive, performative sound system.

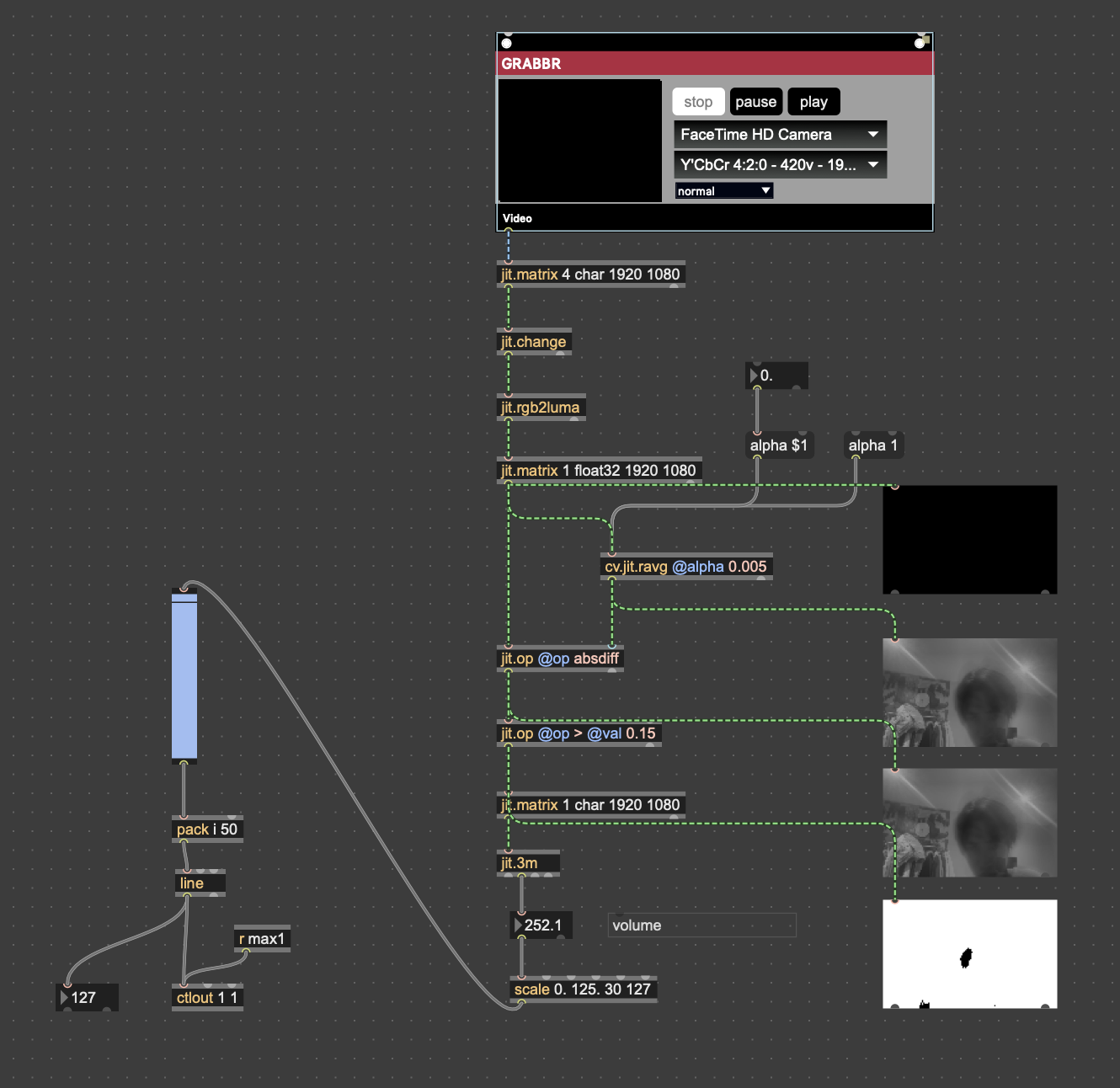

Motion-Triggered Volume Control with Max/MSP

One of the interactive elements in my sound design setup uses the laptop’s built-in camera to detect motion and map it to volume changes in real-time.

Here’s how it works:

I use the Vizzie GRABBR module to grab the webcam feed, then convert the image into grayscale with jit.rgb2luma. After that, a series of jit.matrix, cv.jit.ravg, and jit.op objects help me calculate the amount of difference between frames — basically, how much motion is happening in the frame.

If there’s a significant amount of movement (like someone walking past or waving), the system treats it as “someone is actively engaging with the installation.” This triggers a volume increase, adding presence and intensity to the sound.

On the left side of the patch, I use jit.3m to extract brightness values and feed them into a scaled line and ctlout, which eventually controls the volume either in Logic (via MIDI mapping) or directly in Max.

This approach helps create a responsive environment: when nobody is around, the sound remains quiet or minimal. When someone steps in front of the piece, the sound blooms and becomes more immersive — like the installation is aware of being watched.

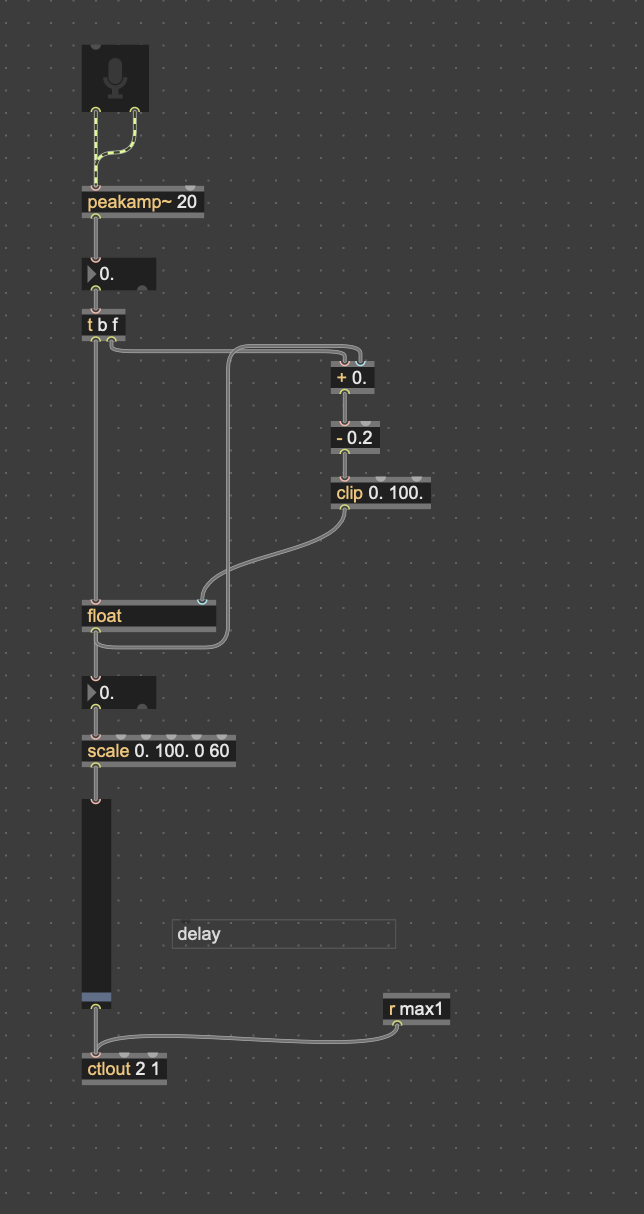

Microphone-Based Interaction: Controlling Delay with Voice

Another layer of interaction I built into this system is based on live audio input. I used a microphone to track volume (amplitude), and mapped that directly to the wet/dry mix of a delay effect.

The idea is simple: the louder the audience is — whether they clap, speak, or make noise — the more delay they’ll hear in the sound output. This turns the delay effect into something responsive and expressive, encouraging people to interact with their voices.

Technically, I used the peakamp~ object in Max to monitor real-time input levels. The signal is processed through a few math and scaling operations to smooth it out and make sure it’s in a good range (0–60 in my case). This final value is sent via ctlout as a MIDI CC message to Logic Pro, where I mapped it to control the mix knob of a delay plugin using Logic’s Learn mode.

So now, the echo reacts to the room. Quiet? The sound stays dry and clean. But when the space gets loud, delay kicks in and the texture thickens.

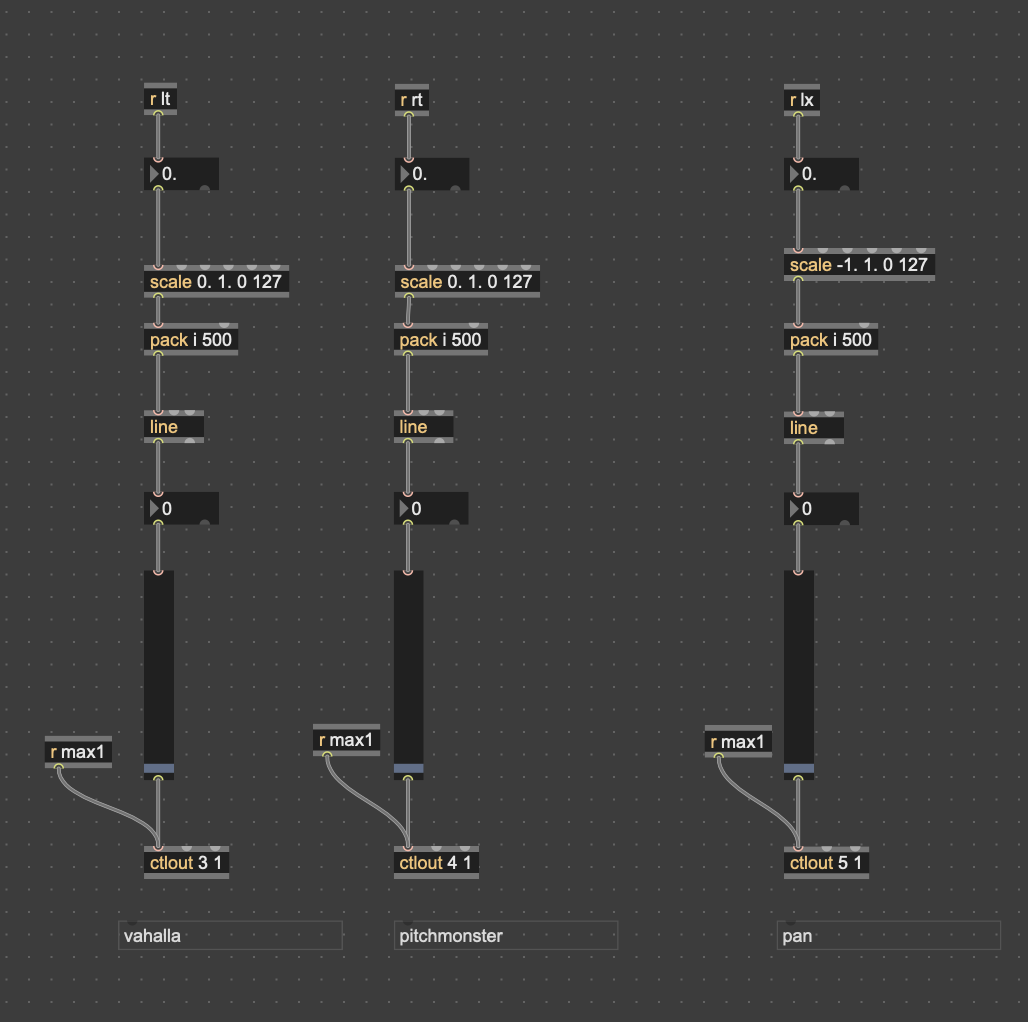

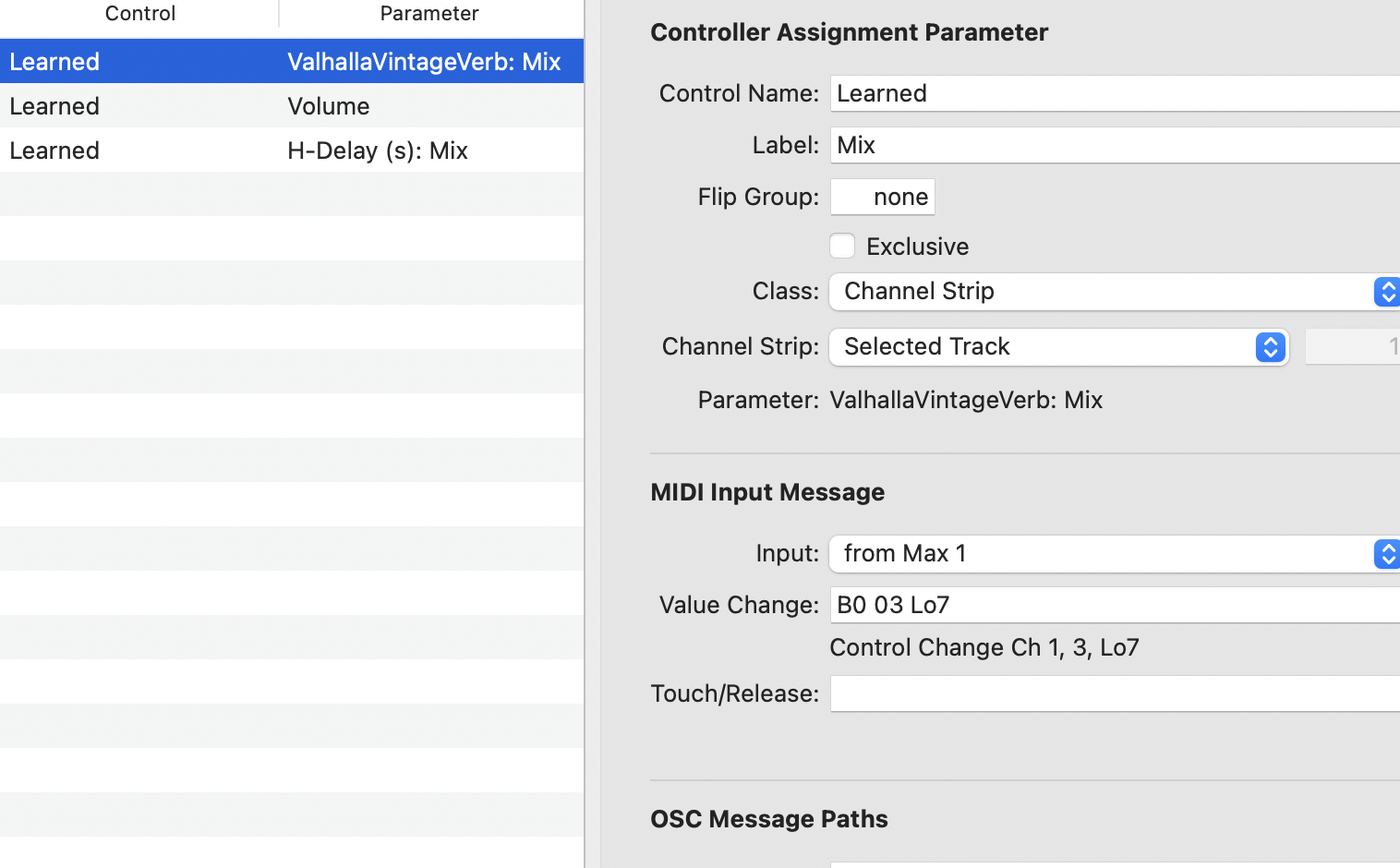

Real-Time FX Control with Xbox Controller

To make the sound feel more tactile and performative, I mapped parts of the Xbox controller to control effect parameters in real time. This gives me a more physical way to interact with the audio — like an expressive instrument.

Specifically:

Left Shoulder (lt) controls the reverb mix (Valhalla in Logic).

Right Shoulder (rt) controls the PitchMonster dry/wet mix.

Left joystick X-axis (lx) is used to pan the sound left and right.

These values are received in Max as controller input, scaled to the 0–127 MIDI CC range using scale, and smoothed with line before being sent to Logic via ctlout. In Logic, I used MIDI Learn to bind each MIDI CC to the corresponding plugin parameter.

The result is a fluid, responsive FX control system. I can use the controller like a mixer: turning up reverb for space, adjusting pitch effects on the fly, and moving sounds around in the stereo field.

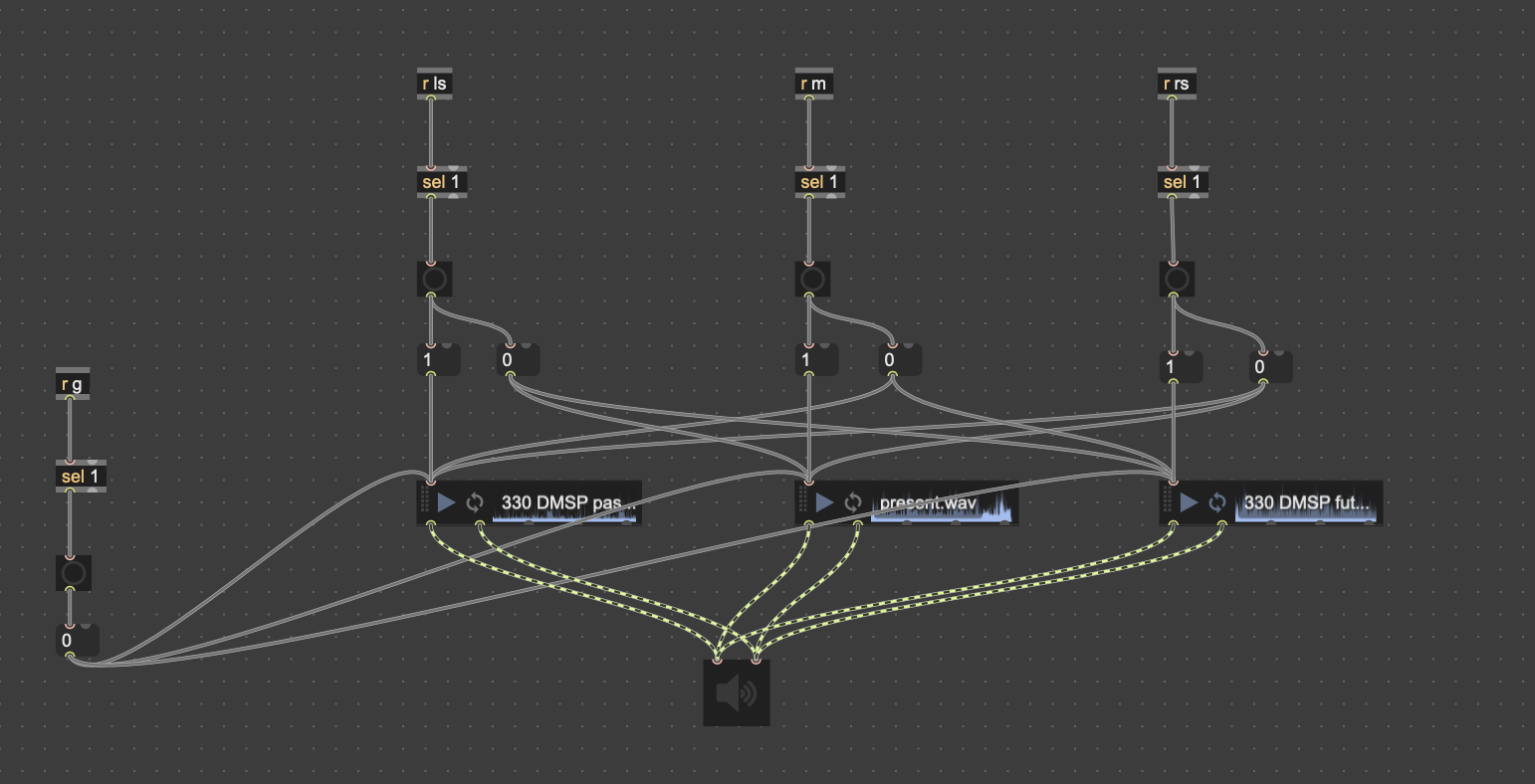

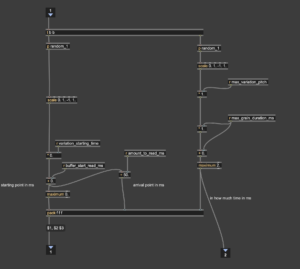

Layered Soundtracks for Time-Based Narrative

To support the conceptual framing of past, present, and future, I created three long ambient soundtracks that loop in the background — one for each time layer. These tracks serve as the atmospheric foundation of the piece.

In Max, I used three sfplay~ objects loaded with .wav files representing the past, present, and future soundscapes. I mapped the triggers to the Xbox controller as follows:

Left Trigger (lt): plays the past track

Right Trigger (rt): plays the future track

Misc (Menu/Back) Button: plays the present track

Start Button: stops all three tracks

Each of these is routed to the same stereo output and can be layered, looped, or faded in and out depending on how the controller is played. This gives the audience performative agency over the timeline — they can “travel” between sonic timelines with the press of a button.

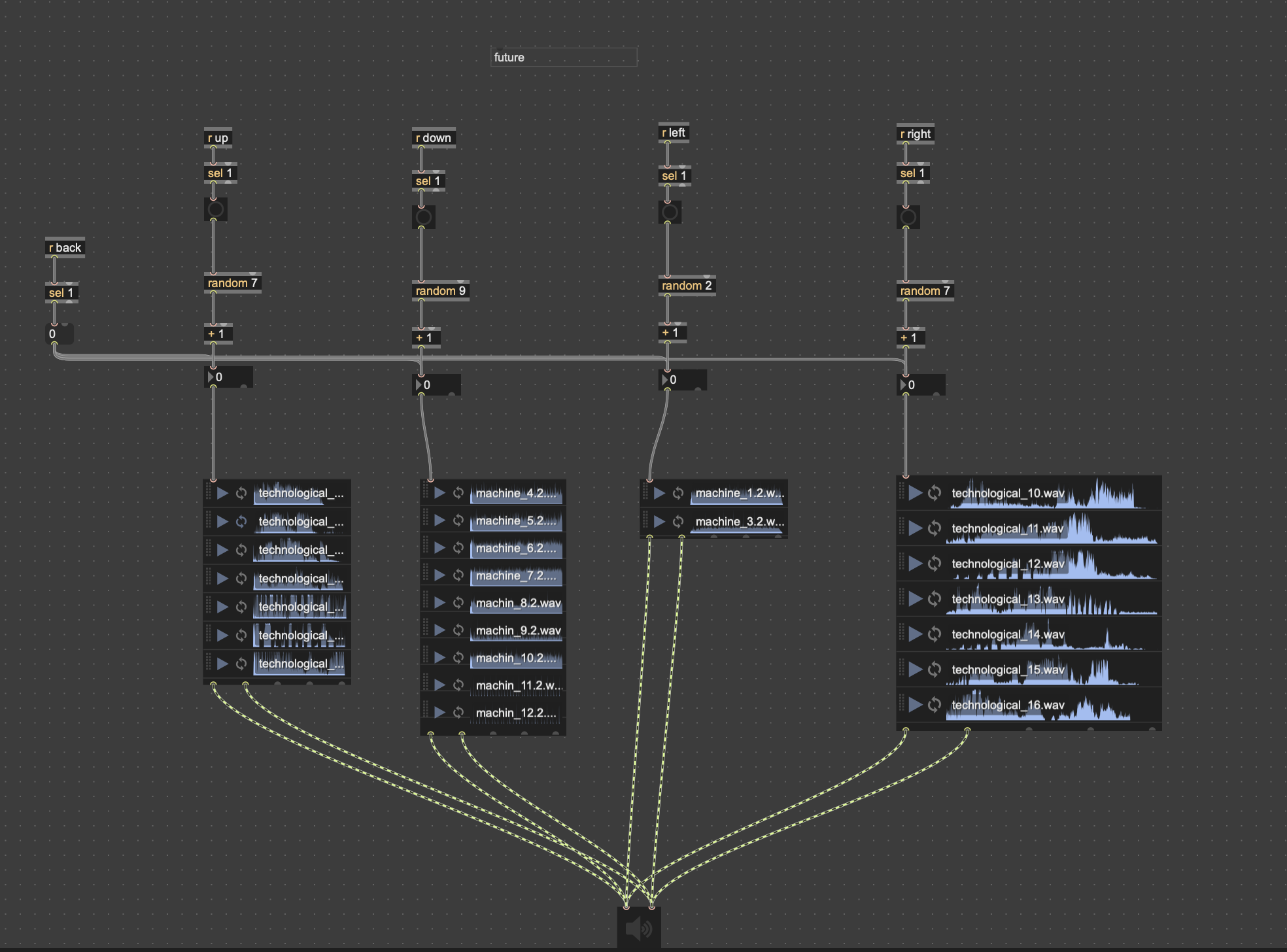

Randomized Future Sound Triggers

To enrich the futuristic sonic palette, I created a group of short machine-like or electronic glitch sounds, categorized as “future sounds”. These are not looped beds, but rather individual stingers triggered in real time.

Each directional button on the Xbox controller (up, down, left, right) is assigned to trigger a random sample from a specific bank of these sounds. I used the random object in Max to vary the output on every press, creating unpredictability and diversity.

Up (↑): triggers a random glitch burst

Down (↓): triggers another bank of futuristic mechanical sounds

Left (←) and Right (→): access different subsets of robotic or industrial textures

The sfplay~ objects are preloaded with .wav files, and each trigger dynamically selects and plays one at a time. This system gives the audience a sense of tactile interaction with the “future,” as each movement sparks a unique technological voice.

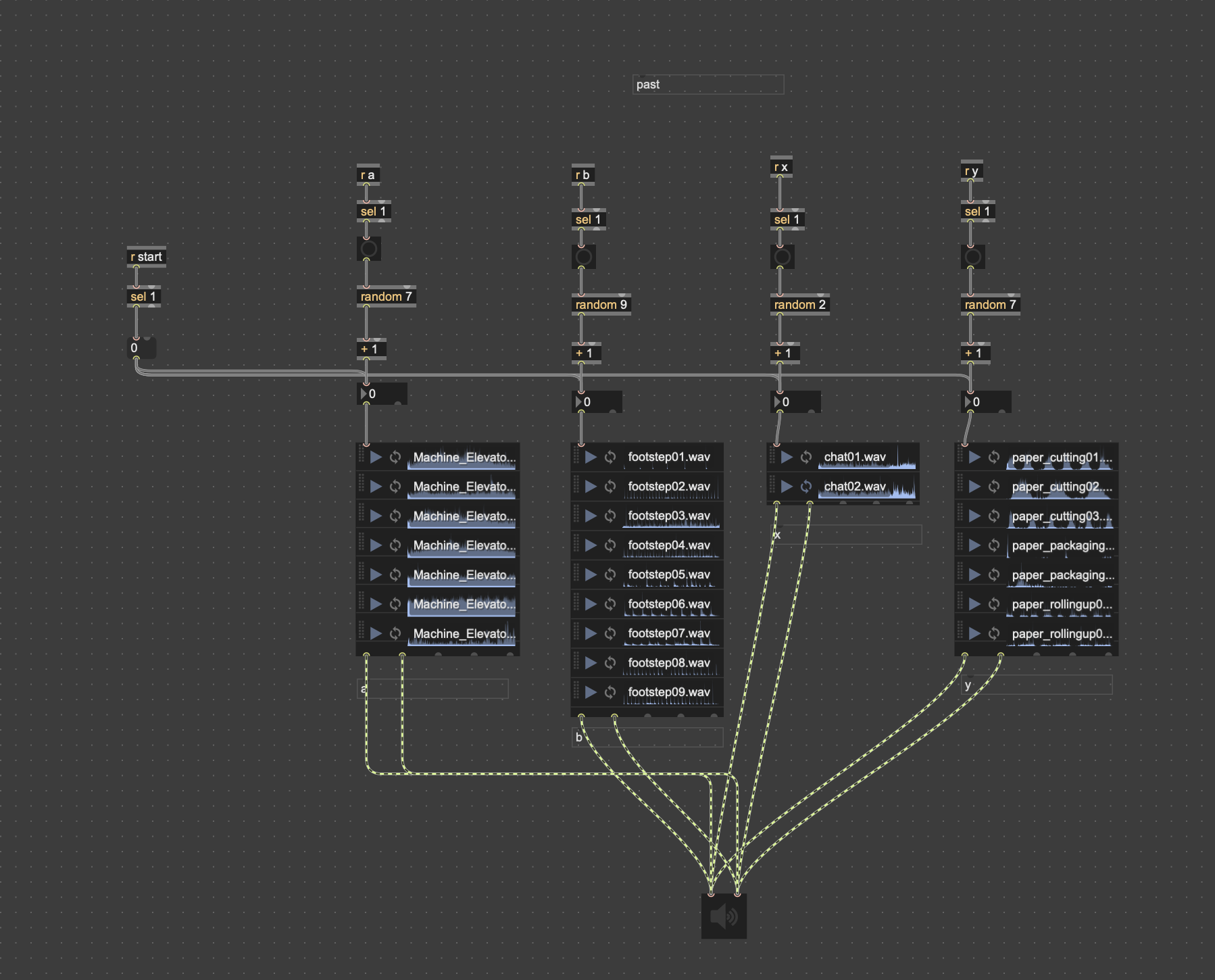

Past Sound Triggers

To contrast the futuristic glitches, I also created a bank of past-related sound effects that reference the tactile and physical nature of the paper factory environment.

Four Xbox controller buttons — A, B, X, and Y — are each mapped to a different sound category from the past:

A: triggers random mechanical elevator sounds

B: triggers various recorded footsteps

X: triggers short fragments of worker chatter

Y: triggers paper-related actions like cutting or rolling

Each button press randomly selects one sound from a preloaded bank using the random and sfplay~ system in Max. This randomness gives life to the piece, allowing for non-repetitive and expressive interaction, as each visitor might generate a slightly different combination of past memories.

This system works in parallel with the future sound triggers, offering a way to jump across time layers in the soundscape.

To make the sound experience more responsive and interactive, I connected Max/MSP with Logic Pro using virtual MIDI routing. This lets Max send real-time control data straight into Logic, so audience actions can actually change the sound.

Here’s what I’ve mapped:

ValhallaVintageVerb: Mix – This reverb mix is controlled by the Left Shoulder button on the Xbox controller. The more it’s pressed, the wetter and spacier the reverb becomes.

H-Delay Mix – This delay’s wet/dry ratio is controlled by how loud the environment is, using a microphone input. When the audience makes louder sounds, the delay becomes more pronounced.

Track Volume – This is controlled by the amount of motion in front of the camera. I use a computer webcam and optical flow to detect how much people are moving — more movement means higher volume.

Pan (Left-Right balance) – Controlled by the left joystick’s X-axis on the Xbox controller. Pushing left or right shifts the sound accordingly in the stereo field.

All these parameters are connected using Logic’s Learn Mode, which allows me to link MIDI data from Max (via from Max 1 port) directly to plugin and mixer parameters. That way, everything responds live to the audience — whether it’s someone waving, talking, or using the controller.

Written by Tianhua Yang(s2700229) & Jingxian Li(s2706245)

In this phase of the project, I am exploring how to remotely control effect parameters in Logic Pro using Max/MSP. Instead of focusing on sound processing within Max/MSP, the goal is to use Max/MSP as an interactive controller, transmitting parameter data via MIDI CC (Continuous Control Messages) to enable real-time adjustments of effects in Logic Pro.

I have now decided to use MIDI CC as the data transmission method between Max/MSP and Logic Pro, allowing for a more direct mapping of effect parameters while providing a smooth control experience.

How will the audience interact?

Which effect parameters should be controlled?

Mapping MIDI CC Between Max/MSP and Logic Pro

The next phase of development will focus on integrating sound selection and playback mechanisms to enhance the system’s flexibility and dynamism.

Once these questions are addressed, I will further refine the interaction model in Max/MSP, ensuring that user gestures, controllers, or spatial movement can intuitively and smoothly influence Logic Pro’s sound processing, creating a more dynamic and immersive experience.

This approach ensures clear interaction logic, immersive auditory experience, and intuitive control, ultimately building an interactive sound environment that seamlessly connects real-world actions with digital sound processing. More updates will follow as the system evolves!

Written by JIngxian Li(s2706245)&Tianhua Yang(s2700229)

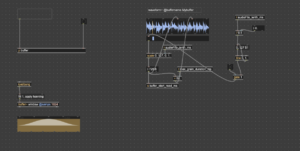

Over the past few weeks, I have been focusing on developing sound processing tools in Max/MSP as part of my project. One of the key components I have completed so far is a sound particle effect processor, which allows me to manipulate audio in a granular fashion. This effect will play a significant role in shaping the sonic textures of the final installation, helping to deconstruct and reconstruct the recorded industrial sounds in a dynamic way.

At this stage, I have not yet fully determined the interaction methods that will be used in the final installation. Since the nature of audience interaction will depend heavily on the collected sound materials and the spatial design of the installation, I have decided to finalize these aspects after the preliminary sound collection and 3D modeling phases are complete. This will ensure that the interaction methods are well-integrated into the overall experience rather than being developed in isolation.

My next step is to continue building additional sound processing tools in Max/MSP, refining effects that will contribute to the immersive auditory landscape of the project. These may include spatialized reverberation, frequency modulation, and real-time sound transformations that respond to audience engagement.

By structuring the development process this way, I aim to first establish a versatile set of sound manipulation tools, then tailor the interaction mechanics based on the specifics of the sound environment and installation setup. This approach will allow for greater flexibility and ensure that the interactive elements feel natural and cohesive within the final experience.

I will provide further updates once I begin the field recording phase and initial modeling work, which will be crucial in shaping the interactive framework of the project.

Written by Jingxian Li(s2706245) & Tianhua Yang(s2700229)

This project is based on the Hidden Door paper mill site as a sound collection point and is presented in an independent exhibition space as an immersive sound installation, exploring the hidden sounds within industrial ruins.

The paper mill was once a space filled with sound—machines operating, paper rustling, workers conversing—all forming its sonic history. But when production ceased, these sounds seemed to disappear with time. But do sounds truly vanish?

This project does not attempt to restore history but rather to decode the sonic information still embedded within the paper mill. Using contact microphones, ultrasonic microphones, and vibration sensors, we will capture imperceptible vibrations and resonances from the factory’s walls, machinery, floors, and pipes, then process and reconstruct them in the exhibition space.

In the exhibition, visitors will enter a sonic archaeology lab, where they will not passively listen but instead actively explore, touch, and adjust the way sounds are revealed, uncovering the lingering echoes of this vanished space.

We often assume that when a physical space is abandoned, its sounds disappear along with it. However, materials themselves can retain the imprints of time—metals, wood, and pipes still carry the vibrations they once absorbed. This project challenges our understanding of the temporality of sound, using technological tools to reveal auditory information that still lingers, hidden within the structures.

Traditional sound experiences involve direct listening, but this project disrupts the intuitive concept that “hearing = sound.” Instead, visitors must actively decode the auditory information embedded within the structure of the space. This shifts how we perceive sound and raises the question: Is the world richer than we consciously realize?

If we cannot hear certain sounds, does that mean they do not exist? If a space is abandoned yet still holds low-frequency vibrations and material resonance, is the factory still “alive”? This project is not just an auditory experience—it is a philosophical inquiry into the boundaries of perception and reality.

In this exhibition, visitors do not hear a fixed historical narrative. Instead, through their exploration, they reconstruct their own version of memory. This makes history not a static record, but an experience that is actively reshaped by each individual.

Ultimately, this project is not just about documenting and replaying sounds—it is about exploring how hearing shapes our perception of space, how the echoes of time can resurface, and how we can bridge the gap between reality and memory.

Written by Jingxian Li(s2706245) & Tianhua Yang(s2700229)

This project explores the themes of time, memory, and space, using sound to “revive” a former paper mill. The abandoned factory has become a silent space, but its memory lingers in the air and within its walls, waiting to be awakened. Meanwhile, another paper mill continues to operate, with machines humming, workers moving, and paper flowing along production lines.

This project brings the sounds of the new paper mill back to the old site, allowing the past to reemerge through sound. As visitors walk through the abandoned factory, they will hear its lost sounds. Their actions will influence how these sounds are presented, causing different layers of time to intersect and creating a unique perceptual experience.

This project is not just about restoring history; it is about using sound to bridge the gap between past and present. It does not simply present the passage of time but examines how memories are stored, forgotten, and reconstructed at different points in time.

Unlike traditional historical reconstruction projects, this is more of a sound-based time experiment. It does not just allow past sounds to resurface; it allows the past and present to exist simultaneously, overlap, and blend into a new, hybrid reality.

In conventional studies of memory, we often rely on visual elements such as photographs, videos, or architectural remains to understand the past, viewing history as static and preserved. However, sound is different; it is fluid, ephemeral, and can only exist in the present moment. This project aims to use sound to demonstrate that time is not absolute but something that can be experienced and reconstructed.

In the abandoned paper mill, the goal is not merely to restore past sounds but to let those sounds continue to unfold in the present. The past and present soundscapes of the two mills will blend and intersect, making them indistinguishable at times. This approach challenges conventional historical recreation, allowing past, present, and future to exist in the same space.

This means that visitors will perceive time through sound rather than through static historical relics. History is no longer just a series of past events; it becomes an interactive, real-time experience that can be altered and reconstructed.

This project does not simply allow the abandoned paper mill to “hear” past sounds; it also lets it “hear” the sounds of the currently operating factory.

This means:

As visitors explore the space, the sounds they hear are not straightforward historical recreations but fragmented memories, recomposed through a process of layering and modification. Every visitor’s journey affects the final form of this “memory.”

Visitors do not passively receive history; they interact with it and change its course. This makes the concept of time more complex, demonstrating that the past is not always absolute but can be shaped by the present.

The physical space of the paper mill has been abandoned, yet its “sonic space” is being relocated there, making it sound as if it is still alive. This creates a sense of dissonance for visitors:

In this project, sound revives a dead space, but the result is not a recreation of the original factory—it is a projection of memory. It is both past and real, but its authenticity is determined by the perception of the visitor.

This project challenges the boundary between physical space and sonic space, prompting visitors to ask: What is real? If a physical space disappears but its sounds persist, does it still exist?

A defining feature of this project is that visitors are not forced to “listen to the past”; instead, they are given the power to shape their experience. Their actions determine the final outcome:

This means that:

This raises important questions: Can we truly restore the past, or is every act of remembering also an act of reinvention? Should memory be shaped by personal perception, or should it be faithfully recorded?

Unlike projects that aim to faithfully recreate the past, this project focuses on exploring how memory is shaped, forgotten, and reconstructed over time.

Traditional historical restoration seeks to recreate a space’s soundscape as accurately as possible. This project, however, allows past sounds to change based on visitor interaction, ultimately resulting in a soundscape where past, present, and future are interwoven.

This means:

This project is not just about exploring the past but also about understanding how memory is constructed. It challenges the notion that memory is absolute, demonstrating that it is always in flux.

This project is not just about sound; it is a reflection on memory, reality, and time.

This project is more than an auditory experience; it is a meditation on how memory is not something stored in time but something that continuously evolves alongside reality. Whether the past truly exists or can be heard depends entirely on how visitors engage with it.

Written by Jingxian Li(s2706245) & Tianhua Yang(s2700229)