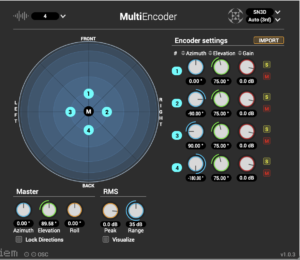

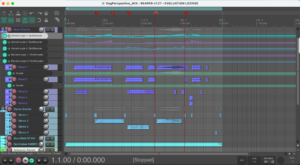

In the “large dog vs small dog” section of the video, since the camera perspective switches back and forth between the two dogs, I applied a similar approach in the sound design. Specifically, I alternated between the two pre-recorded and processed environmental ambience tracks, matching the shift in perspective. This allows the audience to clearly perceive the difference in spatial hearing between the two dogs.

Beyond the environmental ambience, my main focus during the sound design process was adjusting all sound elements except for the dogs’ own vocalisations, especially the EQ and tonal treatment of sound effects and human speech.

From a dog’s perspective, language is not fully comprehensible—what they pick up on are mainly tones, short commands, and key phrases. So, I used AI to generate a segment of human dialogue. I preserved the parts that sounded like clear commands or recognisable short phrases, while processing the rest to obscure the words. The result is a voice that maintains intonation and emotional tone, but becomes unintelligible, simulating how a dog might hear someone speaking without understanding the language.

Additionally, I made a clear distinction between the owner’s voice and the voices of other people in the environment. In a dog’s world, the owner’s voice holds unique emotional weight and should sound different from everyone else.

For the owner’s voice, I used a combination of Phat FX and Step FX. This blend created a sound that is partially unintelligible yet emotionally expressive, preserving the rhythm and tone without full clarity. It contrasts with the later segments where commands are delivered unprocessed, helping to distinguish the emotional impact of meaningful phrases.

For ambient crowd voices and general human chatter, I applied only Phat FX. This gives the sound a more distorted, less emotionally direct quality, where the language becomes vague and the tone more abstract, creating a sonic contrast to the owner’s voice.

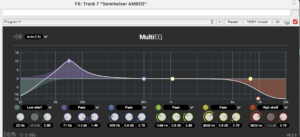

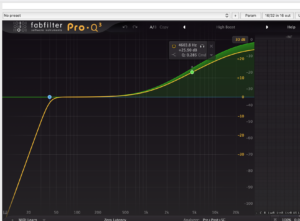

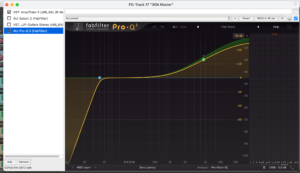

Finally, I adjusted the EQ of all non-dog-originated sounds (environment, effects, and speech) based on the dog’s size and presumed hearing characteristics:

For larger dogs, I boosted low frequencies and reduced highs, creating a broader, fuller sense of hearing.

For smaller dogs, like Chihuahuas, I enhanced the high frequencies and cut some lows, narrowing the sound field to make it sharper and more focused.

Through all of these audio decisions, my goal was to ensure that the audience not only sees the world through each dog’s eyes but also hears the world as each dog might—highlighting how size, focus, and emotional connection shape the canine listening experience.