Zixuan:

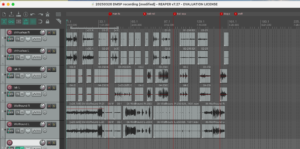

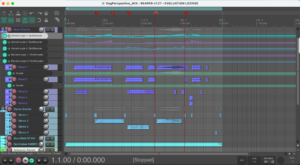

Today, we recorded environmental sound using the Sennheiser AMBEO VR microphone. We captured three separate recordings at the same location, with the only difference being the recording height, to simulate how dogs of different sizes perceive their surroundings.

Since the Chihuahua is very small, we couldn’t find a mic stand low enough to match its ear level. So we rested the microphone directly on the mic stand at a low angle to approximate its actual height.

For the Labrador and the Irish Wolfhound, we recorded at approximately 60 cm and 120 cm from the ground, respectively, to match their standing ear positions.

After recording, I processed the environmental sound recordings for the large dog and small dog perspectives, making adjustments based on their body size and likely auditory characteristics.

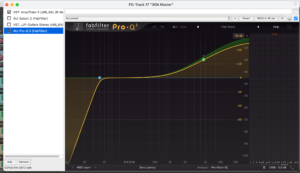

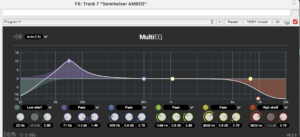

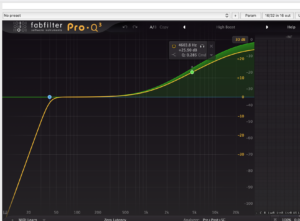

Larger dogs (such as the Irish Wolfhound) have larger body sizes and ear membrane areas, which make them generally more sensitive to low frequencies and less responsive to high frequencies. So, in post-processing, I boosted the low frequencies and slightly reduced the highs while also widening the stereo image to create a broader, fuller auditory space.

Smaller dogs (like the Chihuahua) are typically more sensitive to high frequencies but less responsive to lows. Therefore, I enhanced the high frequencies, reduced some of the lows, and narrowed the overall sound field to create a more focused, sharper listening perspective.

With these adjustments, we aim to authentically simulate how dogs of different sizes hear the world, enhancing the immersive quality of the experience and reinforcing the concept of “listening from a dog’s perspective.”

Ruiqi:

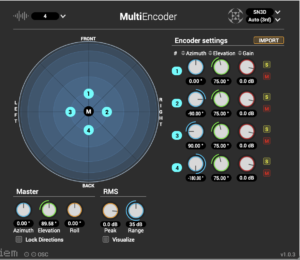

That was what I did on atmos for Labrador. Dogs typically hear frequencies from 40 Hz to 45,000 Hz, way far exceeding human hearing (20 Hz–20,000 Hz). They are most sensitive to higher frequencies (2k–45 kHz), which are critical for detecting sounds like prey movements, high-pitched whistles and orders. And I think amplifying 4k Hz can make sounds like human footsteps and verbal commands more perceptible.

Carly:

When recording the the ambience I made sure of having a measuring tape so we could get the correct size, the thing is that while recording the ambience it was still the plan to use the photos taken with the camera rather than the phone, which is the reason we had the measuring tape too so we could have the correct height.