Collected over the course of years and with painstaking care by Rev Kenneth Mackenzie (Coll-64) –an activist for human rights, members of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, and later assessor of the Race Relation Act 1968 under invitation of the State Secretary–, a staggering number of newspaper articles in our archives detail the history of ‘racial relations’ in Britain during the years when the Civil Rights Movement was making waves across the pond, and political and cultural debates about the issue of racial discrimination were beginning to take centre stage all across the UK and Europe. This section of history, as gathered by Rev Mackenzie, offers an insightful and illuminating look into the legislative and institutional fight for racial equality in Britain, a fight that begins in Mackenzie’s collection with the text to the Racial Relations Act 1965:

A person discriminates against another person, within the meaning of the Act, if he refuses or neglects to provide entry, service or facilities to another person on grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins, or if these services or facilities are not offered on the same terms and in the same way as to general public. Discrimination includes the segregation of persons within a public place, or the provision of facilities or services only after unreasonable delay, or overcharging.

Annotated, highlighted and grouped into folders according to thematic strands, a number of newspapers clippings in the Mackenzie collection delineate the political background to the Act, as well as its reception and the weight of public opinion on the process of decision making. The overall feeling of dissatisfaction with the new legislation is evident in the many letters gathered by Mackenzie and addressed to the Editors of a number of national newspapers. The problems with the 1965 Bill were multiple: on the one hand, racial discrimination was only taken into consideration in the context of ‘public places,’ to the exclusion of a number of venues of community gathering and social interaction; on the other hand, only ‘the provision of services and facilities’ was accounted for within the Bill, so as to forego many other social circumstances of equal significance to community life. The effective exclusion of such a wide range of potential areas of contention neglected to take into account the consequences of discriminatory acts in the fields of labour, marketing, finance, health and education. In addition, the Race Relations Board, the institutional organisation officially charged with investigating complaints of racial discrimination, was only empowered to act by ‘try[ing] to settle’ complaints ‘by means of conciliation between the two parties concerned, and by getting an assurance from the person against whom the complaint was made that he will not practise unlawful discrimination in future.’ Because the Board did not have the power to carry out penal and or civil proceedings –penal proceedings not being contemplated by the Bill, and civil ones only reserved for the intervention of the Attorney General and the Lord Advocate–, and because no official warning nor threat of repercussions could, within the parameters of the Act, come into effect, the Bill practically resulted in the absence of any significant change in favour of the deterrence and prevention of racial discrimination.

The string of articles selected by Mackenzie clearly depicts a rapid and conscious turn against the 1965 Bill, as the editorial boards of both national and local newspapers chose to put racial relations at the forefront of public media, and dedicated front pages, in-depth reports and supplements to the issue. Mackenzie, whose ‘crusade interest was no mere sentimental or uninformed passion,’ took great pains to collate a selection of different outlets looking at the Act from different angles and perspectives, and accounting for the variety of coverage that ‘racial relations’ demanded. When voices regarding the creation of a new and amended Racial Relations Act started to circulate in 1968, then, Mackenzie ensured the opinions of supporters of a new Bill would be documented:

What is disturbing is that no mention was made […] about enforcement procedures, in which the current legislation is particularly deficient. (Tribune, 1.3.1968)

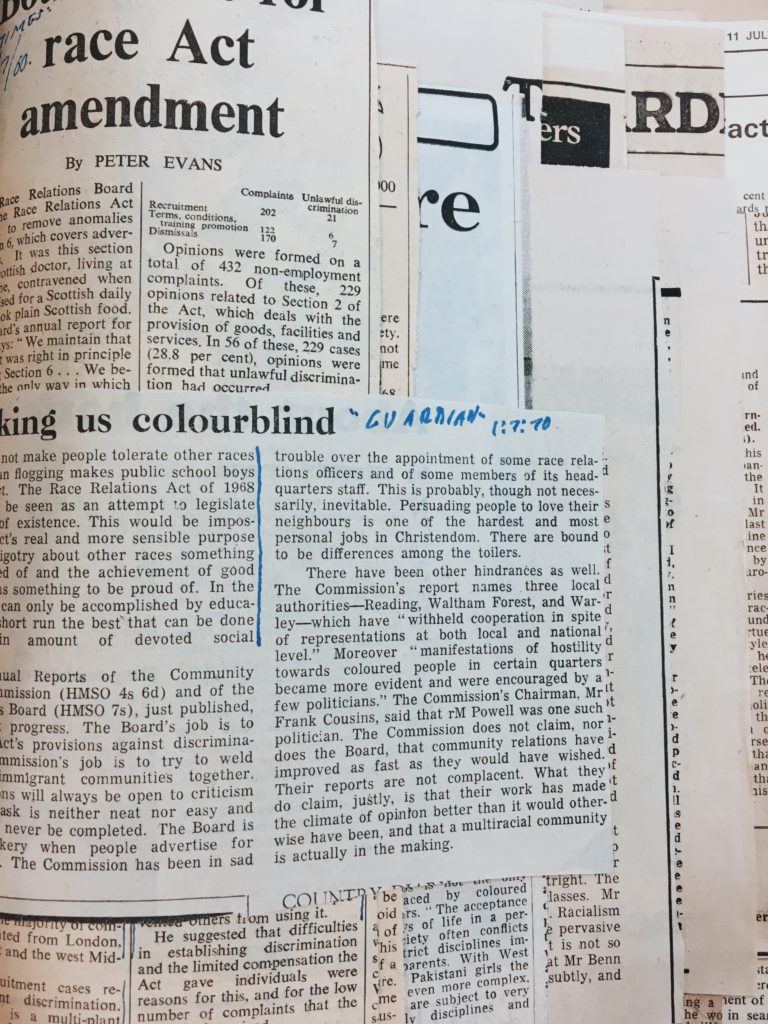

As the newspaper clippings demonstrate, those who promoted amendments to the 1965 Act were particularly vocal about the necessity to broaden the definition of discrimination as well as empowering the Board of Racial Relations with the ability to impart punishing measures onto uncooperative offenders. Despite leaving some unsatisfied –Mackenzie highlighted a number of articles detailing the grievances of political parties and the public alike–, the new Bill, eventually coming into effect in November 1968, did present significant alterations to the 1965 Act. As the original text suggests:

For the purpose of this Act a person discriminates against another if on the ground of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins he treats that other, in any situation […], less favourably than he treats or would treat other persons.

With a detailed lists of potentially discriminatory ‘situations’ that included, but was not limited to, advertising, housing, banking, and employment, the Act now covered significantly more ground than its predecessor, and was welcomed by many, including Mackenzie himself, as a step forward in the protection of Britain’s racial minorities. However, as events immediately following the release of the 1968 Bill would demonstrate, the reach of these changes was not, as yet, quite as far as Britain would have needed given the political climate of the time.

Indeed, as Parliament prepared for the circulation of the revised statute, Conservative MP for Wolverhampton Enoch Powell was reported by national press to have called, in a speech at the Rotary Club of London Annual Conference, ‘for large-scale repatriation’ of immigrants, ‘preferably organised by a special ministry’ (The Guardian, 18.11.1968). Mackenzie dedicated a number of folders to the issues surrounding Powell’s speech, in an attempt, undoubtedly, to highlight the scale and magnitude of the MP’s inflammatory claims. Powell’s focus on ‘coloured immigrants,’ though condemned by many politicians and citizens alike as inhuman and unreasonable, yet evidently received widespread coverage, prompting one reader of The Guardian to question why ‘ideas that were ignored as typical fascist lunacy ten years ago’ (18.11.68) might be receiving such attention on all fronts.

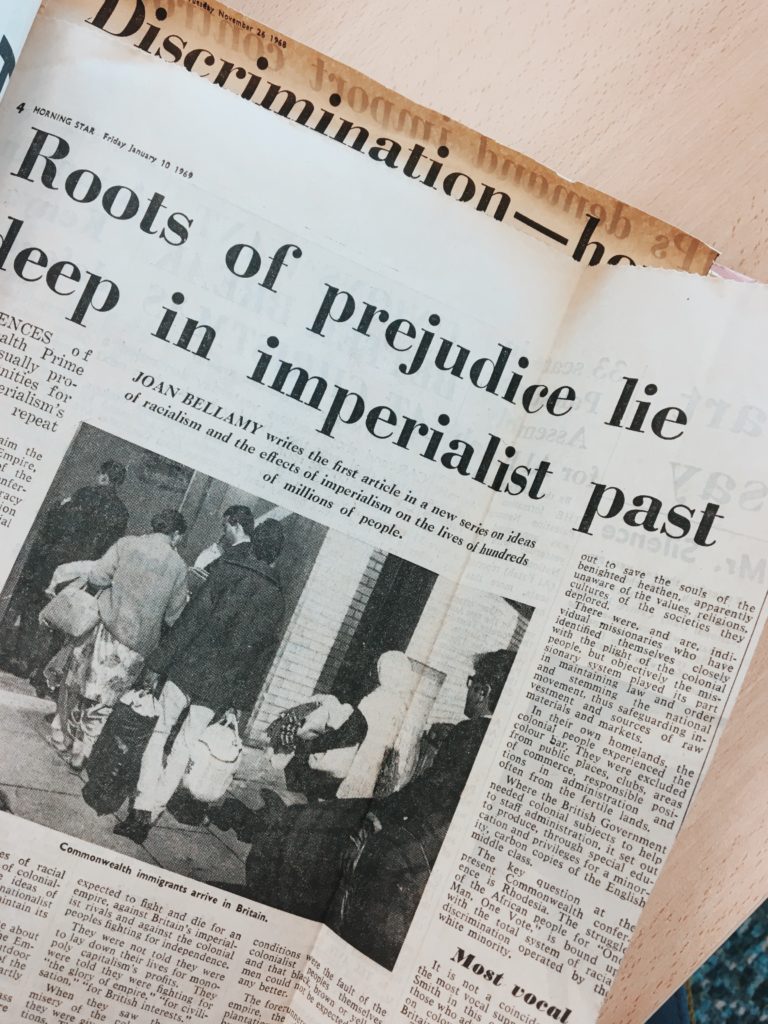

According to Mackenzie’s collection of letters and articles, what made Powell’s tirade against ‘coloured migrants’ particularly appealing to sympathetic audiences was the use of statistics and data that turned the question from one of humanitarian relevance to one made of ‘numbers.’ Yet, as Mackenzie highlights in one of the clipped articles, Powell’s take on ‘facts’ allowed him to ‘select only those facts which enable him to play up to […] fears and prejudices.’ Widely blamed for ‘produc[ing] inadequate statistics and giv[ing] them a false interpretation,’ for ‘confusing the actions of individuals with patterns of behaviour,’ and for ‘obscuring understanding by the rhetoric of unreason’ (The Scotsman, 18.11.1968), Mr Powell himself began being accused of racial discrimination. However, in a bitterly ironic turn of events that underlined the inadequacy of the new Racial Relations Act 1968, no provision was made in the Bill for the prosecution of inflammatory and discriminatory speech. As The Morning Star sorely complained,

In vain did we warn in April that the Bill needed more teeth, and in particular punitive provisions. (26.11.1968)

In Mackenzie’s folders, the storm caused by Powell’s speech, then, is followed by a series of articles examining the merits and demerits of the new, amended Bill, opening the way for a more open investigation in and criticism of the general governmental stance toward the protection and safeguarding of people of colour across the country. In one particularly well-loved 1969 article, whose yellowing paper carries the marks of Mackenzie’s underlining, Frank Cousin, chairman of the Community Regulations Commission, pointed out further inadequacies in the Act’s text by observing that the ‘legislation could combat direct racial discrimination but much voluntary work would be needed to achieve equal opportunity’ (The Guardian, 26.2.1969). By underlining the Act’s inability to forge a long-lasting cultural shift toward a more accepting and equal society, Mr Cousin –and Mackenzie as the attentive reader and collector– put his finger on the hypocritical features of both popular opinion and Government involvement in racial discrimination, wherein the creation of the Act in itself was to be considered as a conclusive solution to the problem of racial discrimination, rather than a mere first step toward what Mr Cousin termed ‘equal opportunities.’

That blind faith in the Act’s power to ‘cure’ Britain of its ‘racial problem’ was indeed a misguided belief became evident with the publication of an inquiry carried out the following year by the National Council for Civil Liberties for a report to the Select Committee on Race Relations, which claimed that ‘coloured immigrants are subjected to hostile treatment by the Home Office and immigration officials’ (The Guardian, 26.5.1970). Mackenzie highlighted the following section:

The report […] accused the Home Office of neglecting human interpretations of the law; aiming to control and exclude at all costs; and of seeing cases as ‘black and white –metaphorically as well as physically.’ (The Guardian, 26.5.1970)

The report demonstrated governmental bias against people of colour, and rendered the issues of racial discrimination once again central in the political debate. Yet, it wouldn’t be until the Race Relations Amendment Act 2000, 30 years after the publication of the report, that legislation began to include a statutory duty on public bodies to promote race equality, and to demonstrate that procedures to prevent race discrimination would be effective. Still today, over 50 years after the Race Relations Act 1968, the ‘equal opportunities’ that Mr Cousin advocated for are far from being a reality, but the history of struggle, revision and amendment collected by Reverend Kenneth Mackenzie can show a path for more radical, inclusive and constructive system of reforms.