Our brief encourages us to explore how to “promote engagement” with the University Art Collection, alongside the guiding question What is the purpose of the Art Collection, how should it be used, and who is it for? While refining our exhibition theme, we’ve been asking our own, related questions:

- How can museums make their collections accessible to the public?

- What does it mean for a collection to “belong” to a public if they are unable to view the works held within it?

- How can people be made aware of collections they may not even know about?

- How do people wish they could interact with collections?

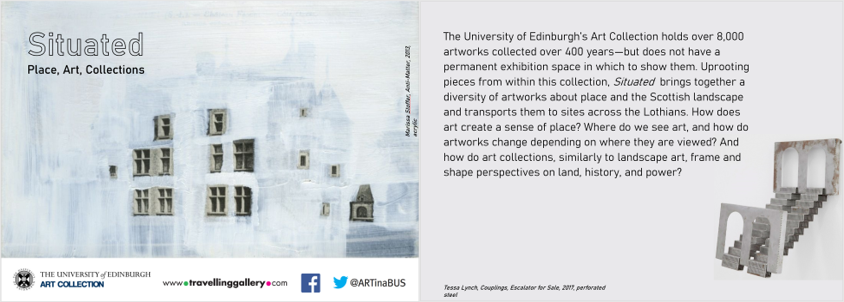

We’ve been thinking about place in art, but have also been reflecting on the contextual place of the collections and exhibitions in which those works are situated. The Art Collection is a unique collection to ask the above questions of. Not only does it not have a permanent exhibition space, meaning that the vast majority of its works are never visible to the public, but as a university collection it is virtually unknown outside of the institution (not to mention the number of individuals at the university who also seem unaware of its existence).

Even aside from these barriers, it can be difficult for members of the public to grasp what a collection is, let alone how it can be relevant to them. While considering these things during our last group meeting, Barbora had the fantastic idea of displaying the works in the Travelling Gallery on collection storage racks. Unlike a “white cube” exhibition model, mounting the works to appear as they are the majority of the time in storage offers a unique way for visitors to encounter the art and consider how it is stored and displayed.

An interesting case study to consider as we discuss these questions, themes, and display techniques comes from the Van Abbe Museum. From November 2013 to July 2017, the Van Abbe Museum ran a project called the DIY Archive as part of their exhibition The Collection Now. The museum describes that “[the DIY archive] was a combination of a storage facility, a workplace and an exhibition space”; visitors were encouraged to take works from the racks and work with museum employees to mount them in their own, temporary exhibition.[1]

As seen in the above video, this rack system was formed of magnetic strips on the wall. However, I got in touch with Aurora Loerakker about the Van Abbe Museum’s use of racks in exhibitions and she additionally directed my attention to their Viewing Depot, which ran from 2006 to 2009 and displayed works on the same racking system used in their collection storage.

The Van Abbe Museum’s use of storage racks in this way is interesting from the perspective of staging an interactive exhibition and inviting public engagement with collection holdings. However, with particular relevance to our project, I am interested in the aesthetic effects of arranging the exhibition space in this way. Although there is, clearly, a lack of scholarship on collection storage hanging, the critical literature on how context informs encounters with art can be usefully extrapolated to our considerations.

A range of studies—both psychological and art critical—have shown that encountering art in a “gallery context enhances the aesthetic experience—both of art appreciation and aesthetic emotions.”[2] Surveying this literature in the context of their own 2019 study, Szubielska et al. also find that in addition to the physical context of being in an art gallery, “elaborative contextual information semantically corresponding to the artwork increases viewers’ ratings of comprehension and/or appreciation.” But what about the effect of the visual contextual information of the gallery space itself?

In 2001, the Walters Art Museum completed an extensive renovation, which included re-installing its artifacts in galleries that aesthetically mimicked their original contexts. In a Washington Post review by Jo Ann Lewis, Museum Director Gary Vikan explained: “What we’re after… is the effect of an icon in a Byzantine church, or a Limoges book cover in a Gothic cathedral.”[3] Lewis comments that the new installations engage the viewer “not only with labels but also with four different audio tours and suggestive, often moody and theatrical (occasionally overly theatrical) installations that echo the architecture of each period.”[4]

Unique installations do run the risk of being overly “theatrical,” and can overwhelm the art or artifacts being shown. However, many critics suggest that the white cube model is not, in fact, without its own risks. In the seminal 1976 trio of articles titled “Inside the White Cube,” Brian O’Doherty outlines how the white cube, rather than being a “neutral” backdrop, is itself an aesthetic object. O’Doherty argues that the white wall context of art galleries has become a “transforming force” that heavily influences the viewer’s experience of the art hung upon them.[5] In this understanding of the gallery space, “context becomes content”: “The wall, the context of the art, had become rich in a content it subtly donated to the art.”[6]

This argument of the almost insidious subtlety of the white wall’s influence continues to inform critical discussion about the role gallery context plays in aesthetic experience. In a 2011 Tate Etc. interview, Charlotte Klonk, Niklas Maak, and Thomas Demand discuss how sensory aspects of gallery spaces are controlled to affect viewers’ experiences. Against these tactics, Charlotte Klonk proposes that what is most important is that the room is honest:

I argue that what makes the Van Abbe Museum’s use of racking effective is how the resulting gallery installations correspond to Klonk’s description of an honest room. Unlike the subtle “illusion” of timeless neutrality created by a white cube gallery, but also unlike the overt theatricality of immersive, sensorially domineering spaces, the use of collection racks to display works is straightforward and honest in its depiction of an active art collection.

Considering the lack of alternatives to the white cube model, O’Doherty writes that “a rich constellation of projects comments on matters of location, not so much suggesting alternatives as enlisting the gallery space as a unit of esthetic discourse. Genuine alternatives cannot come from within this space.”[7] The Van Abbe Museum’s Viewing Depot successfully presents an alternative that enlists not the gallery space, but a place outside of it: the collection storage room. The result is a space that hangs in between storage room, exhibition, public, and private; a fascinating fusion that seems all the more compelling in relation to the unique setting of the Travelling Gallery and its mission to bring contemporary art accessibly and honestly to a diverse audience outside of the white cube model.

[Word Count: 1,097]

Footnotes

[1] “DIY Archive,” Van Abbe Museum, https://vanabbemuseum.nl/en/research/highlighted-projects/diy-archive/.

[2] Magdalena Szubielska, Kamil Imbir, and Anna Szymańska, “The influence of the physical context and knowledge of artworks on the aesthetic experience of interactive installations,” Current Psychology (June 15, 2019): https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00322-w.

[3] Qtd. in Jo Ann Lewis, “Renovated Walters Museum sheds light on its collections,” The Washington Post, October 20, 2001, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2001/10/20/renovated-walters-museum-sheds-light-on-its-collections/77223ecd-06b7-4bdb-905e-4add093dcfd2/.

[4] Lewis.

[5] Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (San Francisco: The Lapis Press, 1986), 45.

[6] O’Doherty, 15; 29.

[7] O’Doherty, 80.

Bibliography

Lewis, Jo Ann. “Renovated Walters Museum Sheds Light on Its Collections.” The Washington Post, October 20, 2001. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2001/10/20/renovated-walters-museum-sheds-light-on-its-collections/77223ecd-06b7-4bdb-905e-4add093dcfd2/.

Maak, Niklas, Charlotte Klonk, and Thomas Demand. “The White Cube and Beyond: Museum Display.” Tate Etc. (January 1, 2011). https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-21-spring-2011/white-cube-and-beyond.

O’Doherty, Brian. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. San Francisco: The Lapis Press, 1986.

Szubielska, Magdalena Kamil Imbir, and Anna Szymańska. “The influence of the physical context and knowledge of artworks on the aesthetic experience of interactive installations.” Current Psychology (June 15, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00322-w.

Van Abbe Museum. “DIY Archive.” https://vanabbemuseum.nl/en/research/highlighted-projects/diy-archive/.

Van Abbe Museum. “Viewing Depot—Plug In #18.” https://vanabbemuseum.nl/en/programme/programme/viewing-depot/.