Hidden Inclusion Is Everywhere

Today in “things that are inclusive and you didn’t realise they are”:

the International Code of Signals (ICS)

We tend to think of inclusion as something modern — a recent design concern introduced in the last decade or two. But hidden throughout history are whole systems that ended up being quietly, unintentionally inclusive because they had to work for everyone, under every condition.

One of the best examples?

The International Code of Signals (ICS).

What is the ICS?

The International Code of Signals is a global communication system used by ships at sea. Long before radios were reliable, vessels relied on flags, lights, shapes, and sound signals to communicate essential information between ships, between ship and shore, or during emergencies.

The modern ICS alphabet was standardised in the mid-19th century, gradually refined by the British Board of Trade, and formally internationalised in the 20th century. The point was simple: every ship in the world, regardless of language, must be able to understand the same messages.

How the system works

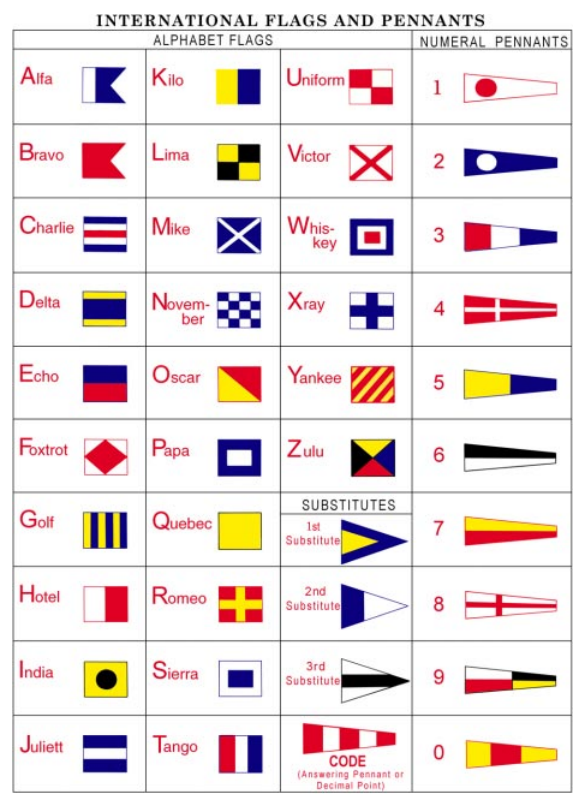

The ICS includes:

-

26 alphabetical flags (A–Z)

-

10 numeral pennants (0–9)

-

3 repeaters (1st, 2nd, 3rd) to repeat letters in hoists

-

Special flags for code groups and signalling conditions

Each flag has a distinctive combination of shapes, stripes, blocks, and layout. Crucially: each flag also carries a meaning beyond its letter.

Examples include:

-

A – Alfa: “I have a diver down; keep well clear.”

-

B – Bravo: “I am carrying dangerous cargo.”

-

O – Oscar: “Man overboard.”

-

V – Victor: “I require assistance.”

It is an entire international language, designed to cut through uncertainty, weather, and linguistic barriers.

Victor means “I require assistance.” or ” Ich benötige Hilfe” or “Je demande assistance.” or “Ég þarfnast aðstoðar.”…you get the idea.

In an emergency even an old times sailor (who historically often couldn’t write or read, as opposed to officers) could raise a “I require medical assistance.” flag (Whiskey) with know how to spell any of that.

So where does inclusion come in?

The ICS had to work:

-

In fog

-

In storm conditions

-

When flags faded in the sun

-

From long distances

-

On ships crewed by people from all over the world

-

And crucially: without relying solely on colour

This last point is where the hidden accessibility appears.

Historically, navies and merchant fleets were overwhelmingly male environments — and roughly 8% of men have some form of colour-blindness. For most of history, there was no colour-vision testing for sailors. You simply took whoever could work a deck, haul a line, or man a watch. (Or in the earlier days of the Royal Navy, any drunk bastard who could make three xxx on a piece of paper and was too drunk to run away…)

If the flag system had depended on exact colour discrimination, it would have failed immediately in real-world use.

So the system was designed to be recognised through pattern, geometry, and contrast, not colour alone.

Why ICS is inherently colour-blind inclusive

Even though the flags are coloured, what actually makes them identifiable is:

-

Horizontal vs. vertical stripes

-

Diagonal bars

-

Chequered patterns

-

Centre squares or blocks

-

Unique proportions

-

Strong dark–light contrast (important in greyscale vision)

-

Shapes that still read correctly when bleached by sun or salt

This means a sailor with red–green colour-blindness (by far the most common) can distinguish “Oscar” from “Zulu”, or “Bravo” from “Hotel”, from the pattern alone.

The ICS is, unintentionally, a great example of pre-modern universal design.

It is inclusion by necessity — because you cannot run a global system that depends on perfect colour perception, perfect weather, or perfect conditions.

A lesson from maritime history

The ICS shows something important:

When a system is designed to succeed under pressure, uncertainty, and real-world conditions, it often ends up being more inclusive.

Accessibility isn’t always a modern invention.

Sometimes, it’s baked into the oldest tools we have — quietly doing its job, unnoticed, because it had to serve everyone long before inclusion became a buzzword.

Hidden inclusion really is everywhere.

Everyone Wins

That’s the heart of it: inclusive design never creates a burden — it creates clarity.

Even with perfect colour vision, I find it far easier to read what the ship in front of me wants because the system was built to work for everyone. Inclusion doesn’t make things easier for disabled people and harder for everyone else; inclusion makes things easier, safer, and more reliable for all of us.