[crossposted from my project: https://whocares.ed.ac.uk/guide ]

A practical guide to University policies for disabled staff

This page includes:

- Reasonable Adjustments Policy (start here)

- Absence Management Policy

- Capability (Performance Management) Policy

- Grievance and Disciplinary Policies

- Digital and Physical Accessibility Policies

- Menopause Policy

- About declaring a disability

- Other important resources

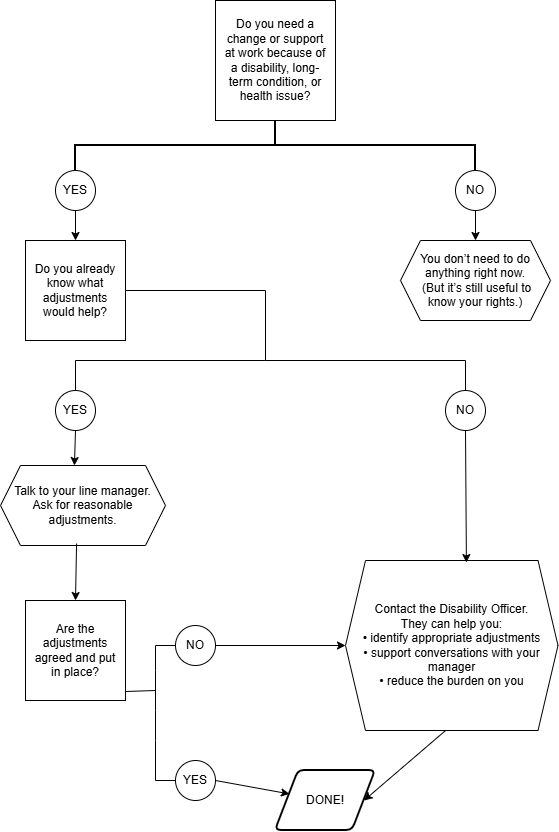

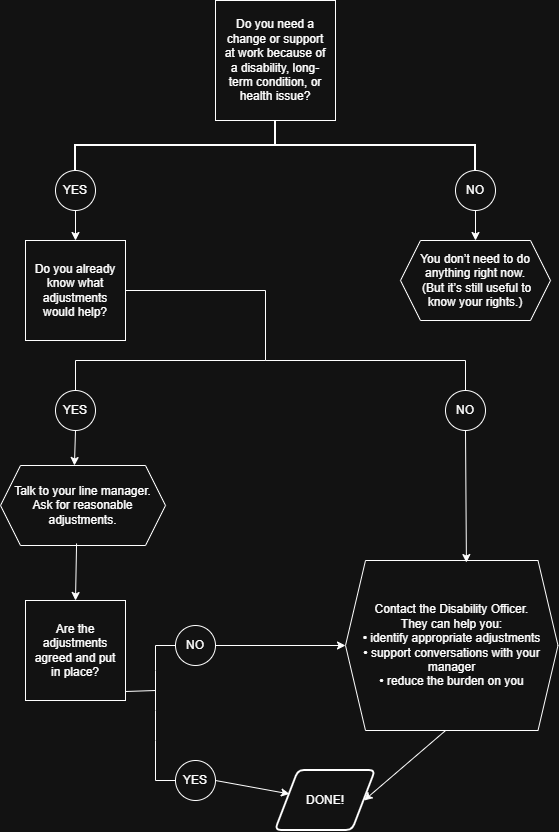

- Flowchart: What to do!

First: you’re not imagining it

The University has over 200 of policies. (All here)

They overlap, cross-reference each other, and are written for different audiences.

That is overwhelming, and very few people — disabled or not — read them all.

This guide is here to:

- point you to the few policies that actually matter most for disabled staff,

- explain why they matter,

- and help you understand what to do in practice, without expecting you to become an HR or legal expert.

The one policy every disabled staff member should read

Reasonable Adjustments Policy

If you only read one policy, make it this one. (Link)

This policy sets out:

- your right to reasonable adjustments at work,

- the University’s legal duties under equality law,

- how adjustments should be requested, considered, and implemented.

Reasonable adjustments can include (but are not limited to):

- changes to hours, workload, or deadlines

- flexibility in location or working pattern

- physical or digital accessibility changes

- support with communication, meetings, or assessment processes

📌 Important:

You do not have to be “visibly disabled”, formally registered, or struggling badly before asking.

Adjustments are about enabling you to do your job on an equal footing, not about proving hardship.

Policies that are especially relevant for disabled staff

You don’t need to read all of these right now — but it is useful to know they exist.

Absence Management Policy

Read here. Disabled staff are statistically more likely to:

- have fluctuating health,

- need time off for treatment,

- experience periods of higher absence.

This policy explains:

- how sickness absence is recorded,

- what happens at review points,

- how disability-related absence should be considered differently.

📌 Why this matters:

If absence becomes an issue, this policy interacts closely with reasonable adjustments.

Knowing this exists helps you advocate early, rather than only once problems arise.

Capability (Performance Management) Policy

The University also has a Capability Policy (sometimes referred to as performance management). Read here.

Disabled staff are statistically more likely to be drawn into capability processes, particularly where:

- health fluctuates,

- fatigue, pain, or cognitive load affect output,

- or reasonable adjustments have not yet been put in place.

This policy explains how the University manages concerns about performance.

📌 Important:

If you are disabled, reasonable adjustments must be considered and put in place first where performance concerns may be linked to disability.

Adjustments should:

- be agreed,

- be implemented properly,

- and be given time to work.

As a rule of thumb, adjustments should normally be in place for around three months before capability or performance management is considered, so it is possible to see whether they resolve the issue.

If capability is raised before adjustments are in place, or without allowing time for them to have an effect, that is a red flag.

If performance concerns arise and you are disabled, you can:

- ask whether reasonable adjustments have been considered,

- contact the Disability Officer for support,

- or seek advice from HR or your trade union.

📌 Key point:

Capability processes should not be used as a substitute for putting reasonable adjustments in place. Knowing this policy exists helps you challenge that early, rather than once a formal process has started.

Grievance and Disciplinary Policies

Read here (grievance) and here (disciplinary).

You don’t need to read these unless you need them — but be aware they exist.

Disabled staff, particularly those with:

- Autism,

- ADHD,

- mental health conditions,

- communication or social differences,

are more likely to:

- be misunderstood,

- experience conflict,

- or find themselves drawn into formal processes.

📌 Key point:

These policies are there to protect you as well.

Knowing they exist means you’re less likely to be blindsided if something escalates.

Digital Accessibility Policy & Physical Accessibility Policy

Read here (Digital Accessibility) and here (Accessibility).

These policies are mostly aimed at:

- people designing buildings,

- managing spaces,

- creating digital content.

But they matter to you too.

📌 Why:

If a building, system, or piece of digital content is inaccessible:

- that isn’t just “unfortunate”,

- it may be a policy breach.

That gives you:

- stronger footing when raising issues,

- clearer routes for challenge,

- and language that moves the conversation from “personal problem” to “institutional responsibility”.

Menopause Policy

The University also has a Menopause Policy. Read here.

Menopause and perimenopause can affect people in very different ways.

Symptoms can be:

- physical,

- cognitive,

- psychological,

- and may fluctuate over time.

For some people, this can have a significant impact on work, including attendance, concentration, memory, temperature regulation, sleep, and energy levels. Therefore it falls under the widest interpretation of the Disability Umbrella.

This policy sets out that:

- support is available,

- reasonable adjustments can be put in place,

- and menopause is treated in the same way as other long-term or fluctuating health conditions.

📌 Key point:

You do not have to “push through”, minimise your symptoms, or wait until things become unmanageable before asking for support. The policy exists to support you, not as a last resort.

A reality check (and some reassurance)

The University is trying to be inclusive.

The policies are there, and in the right spirit. Implementation lags behind, not due to malice but due to systemic issues.

But:

- implementation is uneven,

- knowledge varies wildly between managers,

- and disabled staff often end up doing extra labour just to make things work.

📌 The important bit:

You have rights, and you have policies you can point to.

That matters — even when progress feels slow.

What to do if you need adjustments

If you know what you need

- Talk to your line manager

Ask for reasonable adjustments.Best case, that’s all you need. - If adjustments are agreed, they should be implemented and reviewed, not treated as a one-off favour.

If adjustments aren’t happening, or you’re not sure what you need

- Contact the Disability Officer. Website and email.

Their role is to:- help you identify appropriate adjustments,

- support discussions with managers,

- and reduce the burden on you to “get it right first time”.

This is a normal, supported route — not an escalation.

About declaring a disability

You can register your disability in People and Money.

This:

- helps the University understand how many disabled staff there actually are,

- supports better institutional planning.

📌 But:

You do not have to register your disability to get reasonable adjustments.

Adjustments are available whether or not you formally declare.

Other important resources

- Staff Disability Advice Service/Disability Officer they can advice and support

- Disability Information Service they can help it software, mouses, keyboards etc

- Neurodiversity / Neuroinclusion Hub

- Disabled Staff Network — that’s us!

- Occupational Health while OccHealth can assist with adjustments for medical conditions, they are very rarely your first point of call unless you return from long sickness leave. We would recommend reaching out to the Staff Disability Advice Service first.

You’re not doing this alone!

Flowchart: What to do

Text version of the flowchart

Start.

Ask yourself:

Do you need a change or support at work because of a disability, long-term condition, or health issue?

If the answer is no:

You do not need to do anything right now.

It is still useful to be aware of your rights in case your situation changes in the future.

If the answer is yes:

Ask yourself the next question.

Do you already know what adjustments would help?

If the answer is yes:

Talk to your line manager and ask for reasonable adjustments.

Next, consider:

Are the adjustments agreed and put in place?

If the answer is yes:

No further action is needed at this time.

Review the adjustments later if your needs change.

If the answer is no:

Contact the Disability Officer for support and guidance.

If you did not know what adjustments would help:

Contact the Disability Officer.

The Disability Officer can help you to:

- identify appropriate adjustments,

- support conversations with your manager, and

- reduce the burden on you to work out solutions on your own.

Final outcome:

Adjustments are discussed and agreed, with support if needed.