Is it a coincidence that this post’s title sounds a lot like the Metallica classic “Master of Puppets”—the riff I’ve been trying to master all week? Maybe. But here’s the real question: do I actually get to change that title whenever I want, or is that sense of choice just a clever brain-generated illusion?

There are lots of opinions. I mostly agree with Sam Harris (more on him later) who argues that free will is—let’s say—overrated. But instead of diving straight into a philosophical argument, let’s step back and see what science has to say.

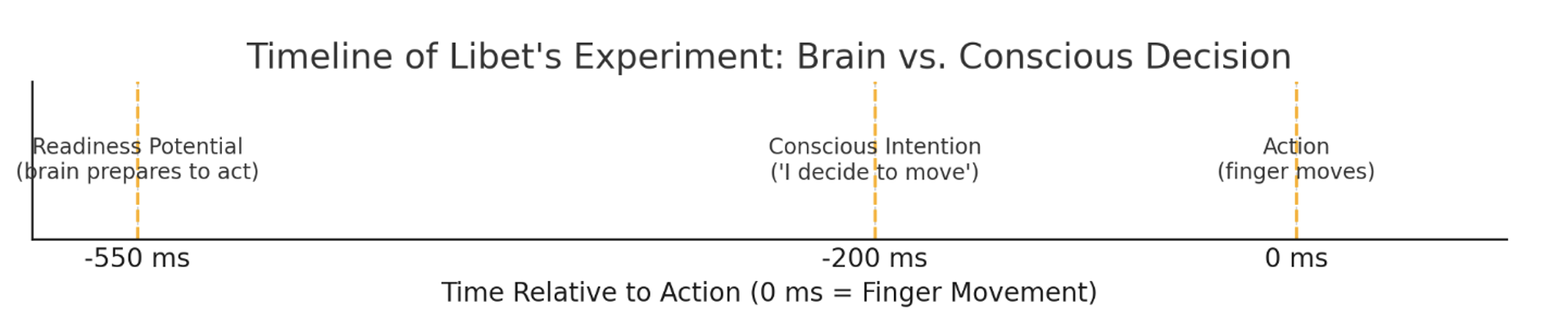

1 The Libet Experiment

Libet placed EEG sensors on volunteers’ scalps and EMG sensors on their wrists, then let them flex a finger whenever they felt like it. After each flick, they read a fast-moving clock and reported where the dot was when the urge first appeared; subtracting a known 50 ms sensory lag gave a “conscious-intention” time roughly 200 ms before movement. However, brain signals called the readiness potential, began about 550 ms before movement which shows neural prep long before the person became aware of deciding.

Why People Still Argue About it?

Even though the Libet experiment has been repeated many times with different methods—like button presses, brain-computer interfaces, or even fMRI—the results still spark debate. Brain activity usually ramps up before people say they made a decision, but what that means isn’t clear.

Critics point out that the original study only had five participants, and it relies on people accurately reporting when they felt the urge to move—something that’s hard to measure precisely.

Most of all, the disagreement comes from interpretation: does early brain activity signal the start of a decision, or is it just random noise? And can simple tasks like flicking a finger really tell us anything about big, meaningful life choices? That’s where the real debate continues.

2 Free Will vs. Free Won’t

Libet didn’t throw free will overboard. He claimed consciousness can veto an action in the ~100–150 ms window between feeling the urge and muscle go-time:

“You can’t pick the song, but you can still stop the music.”

Modern upgrades: In a 2016 brain-computer-interface “duel,” a classifier tried to predict button presses in real time. If the BCI flashed STOP earlier than ~200 ms pre-movement, people could still cancel; any later and the action blasted through—the so-called point-of-no-return [2].

3 Why “Free Won’t” Might Be Wearing a Fake Moustache

- Your brain may brake before “you” do: Researchers have found brain signals that stop a movement popping up a split-second before people feel the urge to cancel. So even the veto seems to start outside awareness [2].

- Noise-not-choice model: Some researchers think the brain is always buzzing with tiny, random signals. Most of the time these signals are too small to do anything, but once in a while they build up just enough to fire off a movement. That slow build-up is the “readiness potential” Libet recorded—it could simply be background noise getting loud, not a planned decision [3].

- Big decisions don’t look the same: When volunteers choose something that really matters—like which charity gets real money—the classic readiness signal often disappears. Instead, the brain takes its time, weighing pros and cons before acting [4].

Bottom line: the “veto window” may not be a conscious super-power at all; it could be just another automatic brain process, or noise, dressed up as free choice.

4 The Free Will Menu: Pick Your Flavour

| View | What It Says | Quick Example | Who Believes It |

| Hard Determinism | Physics pulls every puppet string; you’re just watching them happen. | “I picked tea because of my past, not because I was free.” | Sam Harris, Jerry Coyne |

| Random Brain Noise | Your brain sometimes fires randomly and causes action—no planning needed. | “My brain fired, and I moved—like popcorn popping.” | Aaron Schurger |

| Compatibilism | Even if everything has a cause, you’re free when you act based on your own reasons. | “I chose tea because I wanted tea. That’s enough.” | Daniel Dennett, Sean Carroll |

| Free Won’t | You don’t choose to act, but you can stop yourself just before doing it. | “I almost picked tea, but I stopped myself in time.” | Benjamin Libet (original idea) |

| Libertarian Free Will | Some choices really do come from you, not from causes or randomness. | “I picked tea freely—it wasn’t caused or random, it was me.” | Robert Kane |

5 Conclusion — Where the Evidence Currently Points

Four decades of behavioural, electrophysiological and neuro-imaging studies have converged on a broadly deterministic picture of human action. Readiness potentials, accumulator-style drift toward motor thresholds, and multivariate decoding all reveal neural patterns that predict a choice hundreds of milliseconds—sometimes seconds—before people report deciding [5, 6].

Attempts to rescue a consciously driven “veto” have found only a narrow, unreliable window, and even those suppression signals frequently emerge outside awareness [2]. While philosophical positions such as compatibilism reinterpret freedom within a deterministic framework, few empirical findings today require a non-deterministic explanation. This view doesn’t remove moral responsibility or the need for reflection, but it does shift the burden of proof on any theory that claims actions start consciously without any cause. At present, neuroscience is more comfortably explained by causal neural processes than by self-originating sparks.

References

- Libet, B., Gleason, C. A., Wright, E. W., & Pearl, D. K. (1983). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity. Brain, 106, 623-642.

- Schultze-Kraft, M. et al. (2016). The point of no return in vetoing self-initiated movements. PNAS, 113, 1080-1085.

- Schurger, A., Sitt, J. D., & Dehaene, S. (2012). An accumulator model for spontaneous neural activity prior to self-initiated movement. PNAS, 109, E2904-E2913.

- Maoz, U., Yaffe, G., Koch, C., & Mudrik, L. (2019). Neural precursors of decisions that matter—an ERP study of deliberate and arbitrary choice. eLife, 8, e39787.

- Schurger, A., Hu, P., Pak, J., & Roskies, A. L. (2021). What is the readiness potential? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25, 558-570.

- Braun, M. N., Wessler, J., & Friese, M. (2021). A meta-analysis of Libet-style experiments. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 128, 182-198.