This week, Noëmie Lucas writes about a papyrus document, P. World 121a, described as a “receipt”, a characterisation clearly supported by the presence of the term barāʾa in line 2. The document is incomplete: only its upper part has been preserved. It nevertheless contains interesting information, which I would like to shed some light on in this blog post.

In From the World of Arabic Papyri, A. Grohmann proposes an edition and a translation of the recto of this papyrus. He introduces the document as referring to al-Muʿtazz (232/847–255/869), the Abbasid caliph (r. 252/866–255/869), brother of al-Muntaṣir and son of al-Mutawakkil (r. 232/847–247/861).

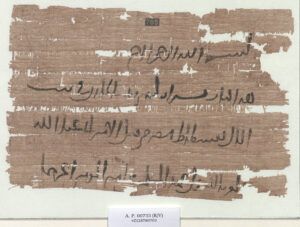

P.World 121a, at the Papyrus Collection of the Austrian National Library, Vienna.

Here is the translation (with minor changes):

- In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful.

- This is the receipt for Muḥammad b. Wahb, the [cashier] (al-khāzin) in the Trea-

- sury in Fusṭāṭ Miṣr, [on behalf] of Abī ʿAbd Allāh

- al-Muʿtazz bi-llāh, designated successor to the throne, son of the Commander of the Faithful, may God strengthen them.

The document includes the title walī ʿahd al-muslimīn (l. 4), meaning “designated successor to the throne”. It also refers to al-Muʿtazz as “son of the Commander of the Faithful” (l. 4). The papyrus must therefore date from the reign of al-Mutawakkil and must have been drafted after 235/849–850, when al-Mutawakkil decided on the succession.

In addition, the document mentions a certain Muḥammad b. Wahb, described as a cashier in the Bayt al-Māl in Fusṭāṭ (ll. 2–3). Muḥammad was the brother of Sulaymān b. Wahb, finance director of Egypt during the caliphate of al-Mutawakkil. Sulaymān was appointed to this position twice. We know in particular that he was serving as finance director in 246/860–861, towards the end of al-Mutawakkil’s caliphate, likely during his second tenure, as attested by the dated papyrus P.Cair.Arab. 198. However, the date of his first appointment remains unknown.

If we assume that Muḥammad b. Wahb was serving as cashier while his brother was also active in Egypt, we still cannot establish the precise date of this document. The titulature found in the papyrus therefore remains the most reliable element for situating it chronologically. The document can be dated between 235/849–850 and 247/861, but it is not possible, in my view, to narrow this range further. Grohmann suggests that the document may date between 242 and 247, but he does not explain the reasoning behind this proposal.

According to Grohmann, “the reason why al-Muʿtazz received money from Egypt is not known; possibly he possessed state domains in this country, the revenue of which was remitted to him by the Treasury” (From the World, p. 121). This interpretation aligns with what the incomplete document suggests. In this context, the receipt may have been issued for the rent of an estate owned by al-Muʿtazz. If so, this document can be added to the corpus of evidence attesting to caliphal-owned estates in Egypt. This issue has been addressed by Marie Legendre, PI of the Caliphal Finances project, in her study “Landowners, Caliphs and State Policy over Landholdings in the Egyptian Countryside: Theory and Practice” (especially section 7, “Authority and Control in the Later Abbasid Period”).

I first encountered this document while collecting papyri that allow for the reconstruction of a list of finance directors appointed in Egypt during the Abbasid period. What initially caught my attention was the mention of this cashier, whom I was able to identify. The document thus provides additional evidence concerning the individuals involved in fiscal administration. The name of Muḥammad b. Wahb is particularly significant, as his familial link with Sulaymān b. Wahb helps us better understand the social profile of those holding such positions.

Why Muḥammad b. Wahb was the recipient of this receipt on behalf of al-Muʿtazz remains unclear. According to the APD, the provenance of this papyrus is al-Fusṭāṭ, a conclusion inferred from the mention of “Fusṭāṭ Miṣr” in the text. However, this reference does not indicate the location of al-Muʿtazz’s estates in Egypt, nor does it allow us to state with certainty that the document itself was written in al-Fusṭāṭ. The mention of the city may simply have been necessary to clarify the identity and position of Muḥammad b. Wahb, who was receiving payment on behalf of another individual.

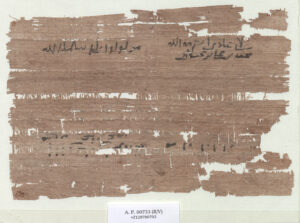

As far as I can tell, the other side of this document remains to be edited, we show an image here which is available at the website of the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

I would like to thank Leone Pecorini-Goodall for his insights about the title “walī ʿahd al-muslimīn” and for sharing his thoughts about this document.

Arabic documents are cited according to “The Checklist of Arabic Documents”.

Banner Image: Free stacks of paper files image, public domain CC0 image.

Leave a Reply