This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship connected to our research. This week, we feature Jennifer (Jenny) Cromwell of Manchester Metropolitan University, Egyptologist and Coptic Papyrologist, and guest of the Caliphal Finances project in 2023.

Could you briefly tell us about your background and career path?

My background is in Egyptology. As part of my BA programme, I studied Coptic in my second and third years, and then again in my MA, for which I also focussed on Coptic documents for my dissertation. This was my first real introduction to non-literary Coptic; I was certain I wanted to work on Coptic material, but not something religious (or at least not overtly religious). This led to my PhD, which started off as something socio-economic and morphed into a detailed papyrological study of the work of a scribe from the village Djeme (Medinet Habu) in the 8th century. After my PhD, I held research positions at the University of Oxford, Macquarie University (Sydney), and the University of Copenhagen, as well as briefer fellowships at the British Museum and John Rylands Library. I joined Manchester Metropolitan University in July 2018.

Jennifer Cromwell

What is your current role, and what does it involve?

I’m Reader in Ancient History, and also the School Research Lead for History, Politics, and Philosophy. Apart from teaching (mainly undergraduate) and research, I spend a considerable amount of time supporting colleagues’ research, especially regarding applying for external funding. I’m also the co-director of the Manchester Game Centre, reflecting my increasing research focus over recent years on both the reception of Egypt in games (analogue and digital) and the use of games as a creative research method.

Can you summarise your main research areas and current projects?

For much of my career since my PhD, my research has focussed on the social and economic history of late antique and early Islamic Egypt, primarily on the basis of non-literary sources, with particular emphasis on Coptic material. I’ve run research projects on scribal practice, as well as monastic economies, reflecting the range of my interests. Over recent years, my research has increasingly branched into broader areas of study, working with heritage organisations and community groups on non-Coptic / non-late antiquity related topics. Yet, late antique village and monastic communities remain one of my main interests, and I’m currently writing a monograph on an archive from Djeme, which examines questions of family, property, patronage, and fiscal responsibilities.

Wat sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

As an Egyptologist, my main interest has always been on Coptic texts, specifically documentary material. They provide evidence for the type of quotidian life that I’m interested in, especially for non-elite lives. The volume of material is considerable and diverse, which is both a strength, but also a problem given the publication nature of much of the material, which was published in the 19th and early 20th centuries, which is often partial and requires considerable time to work with. I’m also interested in the material remains of the sites from which these texts derive, but little of this is preserved, as a result of the excavation history of many late antique settlements; before the mid-20th century, archaeologists in Egypt were rarely interested in preserving these later remains, in favour of the pharaonic material that lay under many of them.

How do fiscal theories, practices, and institutions feature in your work? How are you approaching these topics?

As part of my interest in the reality of day-to-day life at Djeme, it is impossible to avoid fiscal practices. Tax documents, mainly receipts but not only, form a considerable portion of the surviving textual record (ca. 500 receipts on ostraca have been published to date). After starting to work on these particularly from the perspective of scribal activities, i.e., who wrote them, how did the administration of taxes fit into their wider writing practices, I became particularly interested in how fiscal practices were recorded and disseminated throughout the Nile Valley. Djeme was not an important village, but for a couple of decades in the early 8th century, there was an intense period of tax administration. While tax receipts comprise the majority of the evidence, there are also tax demands, communal tax agreements, and other documents that refer to taxes, e.g., travel permits. Examination of taxation at this local (micro) level, allowed broader questions about fiscal policies in early Islamic Egypt to be posed: why was Coptic – rather than Greek or Arabic – used at a local level to administrate tax collection; what role did Coptic play as an official language of the fiscal administration of Egypt? Fiscal practices, for me, have largely been a by-product of my wider interest in who writes what and how these individuals are connected and form part of a larger system, rather than through an intentional interest in the first instance in fiscal history.

In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

I think that some of the prevailing assumptions, such as those of Harold Bell, concerning the ineptitude of the new rulers to administer their new territories, and so a reliance on previous Byzantine practices, has already been challenged. The papyrological sources don’t show an inability to govern, but a pragmatic response to a rapidly changing situation, and these pragmatic responses evolved throughout the 7th and 8th centuries to develop new approaches to administering a multilingual and multicultural country. E.g., Coptic was used in ways that had never been considered – or at least never implemented – under the Romans/Byzantines, and this must be part of an intentional practice rather than a byproduct of removing the constraints on the domains within which Coptic – the indigenous language – could be used in Egypt. Knowledge exchange and technical training do not, and cannot, develop out of nowhere, but must reflect policies (and in this case those relating to fiscal practices) of the country’s rulers.

A big thank you to Jenny for sharing her thoughts with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

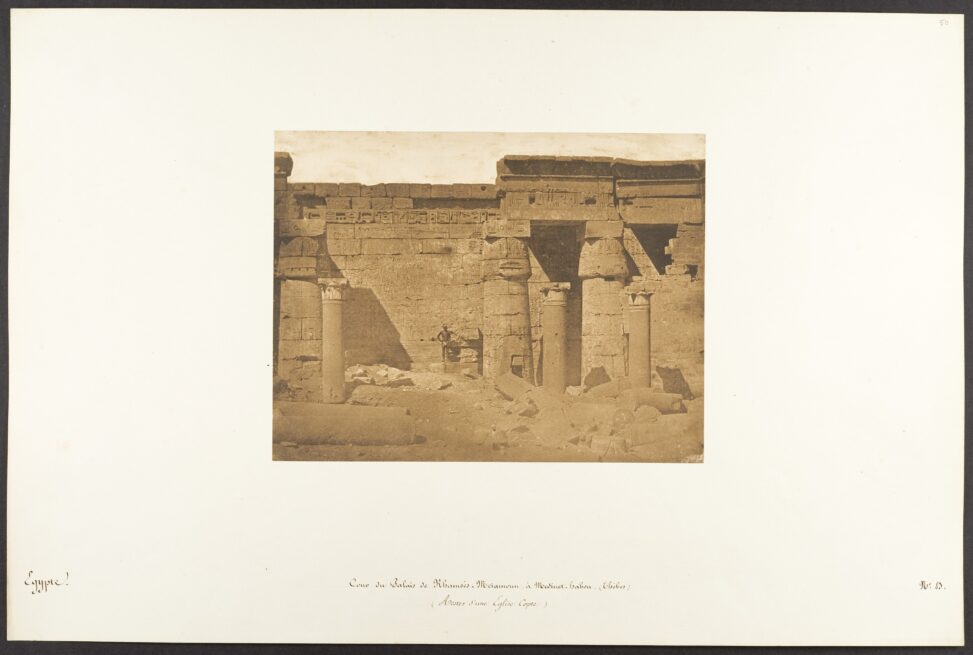

Banner image: Cour du Palais Rhamsès-Meiamoun, à Médinet-habou (Thèbes) (Restes d’une Eglise Copte) (1849-50), Maxime Du Camp (1822–1894). Metropolitan Museum of Art, object 2005.100.376.83.

Leave a Reply