This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship connected to our research. This week, we feature economic historian and former Visiting Postgraduate Researcher of the Caliphal Finances project, Thomas Laver from Cambridge University.

Could you briefly tell us about your background and career path?

As an undergraduate I studied a joint-honours History & Economics course as a way to resolve the difficulty of being stuck between two different subjects when choosing a degree course as a 17-year-old. Alongside my economics training, I then ended up doing History courses on Eurasia 300-900 AD in my first year, and the Eastern Mediterranean 500-700 AD in my second. Those courses made me more and more interested in the great unknowns of pre-modern history – in which so many simple facts of life remain unknown compared to more modern history – as well as the excitement of the world of Late Antiquity more specifically.

During the second of these two courses I asked my tutor for more economic history reading given my cross-disciplinary training, but found the reading he provided starkly different to the economic history I was getting from economists. This prompted me to try to work more on the economic history of the Late Roman and Early Islamic worlds, seeking to bring the two very different types of economic history together. Egypt quickly became a focus of my work given the large mass of documentation from that region, which provides excellent data to work from, even if I’ve had to work with it less quantitatively and more descriptively than I had first hoped! This work then ended up taking me through a masters at Oxford and a PhD at Cambridge to where I am now.

Image provided by Thomas Laver

What is your current role, and what does it involve?

In September-December 2022, I was a PhD Candidate at Cambridge, working on a thesis then entitled “The Economic Organisation of Egyptian Monasteries, and their Role in the Microeconomies of Rural Communities, 400-900 AD”. The name was later shortened, and the focus narrowed! Given the substantial role that the state plays in the economy, I therefore have a significant interest in fiscal affairs, particularly in the early Islamic period where firm answers are scarcer than in the Roman one. This prompted me to come to Edinburgh for a term as a Visiting Postgraduate Researcher, working closely with the Caliphal Finances team and the Centre for Late Antique, Islamic, and Byzantine Studies. My research was enriched through their expertise and my exposure to their discussions.

I completed my PhD in 2025, and have now started an Early Career Research Fellowship (formerly known as a JRF) in History, also at Cambridge. I am continuing my research into the economic history of Late Antiquity, while also starting a new project on the decline & survival of Christian monasteries across the Early Islamic world.

Can you summarise your main research areas and current projects?

My main research interests are threefold: the functioning of the rural economy in the Late Roman and Early Islamic world; the economic activities of monasteries in the Eastern Mediterranean; and the survival of monasteries & Christian communities in the first three or four centuries of Islam.

My interest in the first led me to the second, as the monasteries provide plentiful documents to study for uncovering the realities of economic life in the Late Antique world. My interest in the economic life of the monasteries then led me to an interest in their survival, particularly the question as to whether they really did decline over the 8th and 9th centuries, and if so, why.

What sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

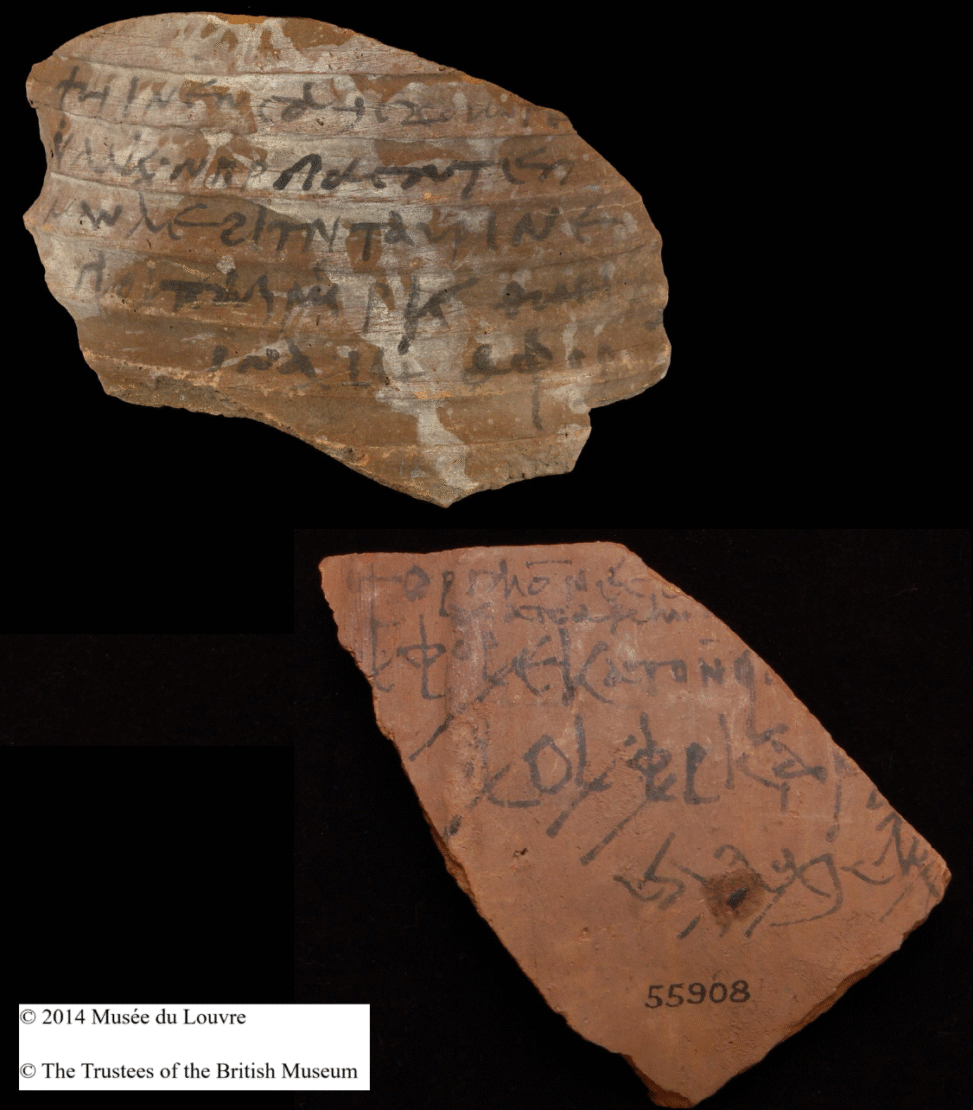

My main focus has – perhaps unsurprisingly – been on papyri and ostraca, on which have been preserved thousands of documents recording daily life in the Late Antique world. These include more verbose sources like letters and contracts, as well as very basic and often formulaic documents like tax records, delivery receipts, and lists. You’d be surprised about the stories you can construct from enough bitty pieces of evidence like this, which can tell us a lot about daily life if properly understood, contextualised, and then synthesised!

While not an archaeologist by training, the physical remains left behind by cities, villages, and monasteries are also key to my work, providing indications of how life worked and a rough chronology of activity at those sites. This can be compared and contrasted with the documentary evidence to build out more developed pictures of life than when using one source alone.

Increasingly as I move into Syria-Palestine, Iraq, and the Jazira, I’m also using more and more chronicles compiled or copied in Christian monasteries, as well as the histories and biographies drawn up by later Arabic authors. These provide multiple different perspectives from which to build a holistic picture of economy, society, and politics across the Early Islamic world. They also differ from the papyri in providing more complete episodes of daily life than the snapshots provided by individual documents, which is always useful!

How do fiscal theories, practices, and institutions feature in your work? How are you approaching these topics?

Fiscal institutions are key to any complete analysis of the functioning of the economy, whether on the local level – in which taxes were a major item of household expenditure – or the regional one, where tax & spend policies were key to the circulation and reallocation of coin and wealth between different areas and groups within the Islamic empire.

When examining local fiscal policy, my questions relate to the scale and nature of fiscal impositions, and how changing fiscal institutions can alter household choices. If your taxes start getting collected more in wheat than in coin, how does that change your approach to farming, or to the market? In turn, this raises questions about the economic history of wider regions: do these realities affect the state’s choice of how to tax? Do the spending priorities of the state start to affect economic exchange and production? Does this change over time? All are fascinating questions for an economic historian that require a proper understanding of fiscal institutions to work on.

As I begin to focus more on the decline of the monasteries, a major fiscal institution in my work has increasingly been the capitation tax, which after its imposition on monks in the early 8th century has been argued to have caused distress and financial weakness to monasteries across the early Islamic world. However, many monasteries appear to be happily paying the tax and surviving (and even actively investing!) for many decades after this, with their economic activities giving them enough spare capacity to weather the additional impositions. Many monasteries even seem to have profited from the positions they held as partners to the early Islamic state, as Cecilia Palombo particularly highlighted through her 2020 PhD thesis.

Thus, even if there was a decline of the monasteries in the 8th and 9th centuries, the capitation tax alone cannot account for it. A closer study of fiscal institutions will help to situate the monasteries within their proper context, not just as persecuted communities, but also as integral parts of the new socio-political order. The failure or survival of individual monasteries must account for this to build a more nuanced picture of the life of Christians in the early Islamic empires.

In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

I think the most interesting area to look at in Islamic fiscal history is not so much the high-level changes, but the lived realities of fiscal policy on the ground. If we look more at the lives of households rather than larger groups (villages, regions, empires), then we will be better able to understand the context in which fiscal policy was made, and the real impact it had throughout the early Islamic empire. This can provide interesting exposition as to how economy, society, religion, and politics all interacted in this period.

Such a bottom-up framing also offers necessary context for stories of either resistance or acquiescence to fiscal changes that appear in the more literary and historical sources. By examining the effects of fiscal policy on the ground, we can start to determine if the opposition to particular policies expressed by these sources was likely to be a fiction of later Christian or Islamic writers (saying more about their period than the one about which they write), a contemporary but exclusively elite concern, or if they did in fact bring about widespread distress and opposition. The village level is particularly important in this framework, as it was the village that could either insulate or expose its members to the vagaries of fiscal policy imposed from above. A greater focus on Islamic fiscal history ‘from below’ is therefore of use not just to understanding the nature and impact of changing Islamic fiscal institutions, but also the sources that we use for studying those institutions.

A big thank you to Thomas for sharing his thoughts with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

Banner image: O.Bawit 4 & O.Sarga 345: Two wine delivery records from the monasteries of Bawit & Wadi Sarga respectively. (Credit: Musée du Louvre & Trustees of the British Museum).

Leave a Reply