A large part of the corpus of the Caliphal Finances project’s research consists of papyri from Egypt, mainly tax receipts and accounts. These papyri can be seen as the working documents of the fiscal administration of the province and reflect fiscal practice on a day-to-day basis. In this post, I want to show you some aspects of the work we have been doing with accounting documents. Within the team, our Principal Investigator, Marie Legendre, has been focusing on Arabic accounts and the birth of Arabic accounting in Egypt, and I have been focusing lately on Greek accounting documents of the 8th century, which present the last phase of Greek as an administrative language in Egypt. I will present here two aspects of my current research: 1. providing editions of previously unpublished accounts, and 2. the use and reuse of these Greek accounting documents.

While Greek had been a language of administration in Egypt since the conquest by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, it has been observed, most recently by Lajos Berkes, that during the 8th century CE, particularly in the latter half, Greek was used in the administration of Egypt solely as a language of accounting. It was used to write numbers, names, abbreviations, and fiscal terminology. Fiscal accounts did not involve complex grammatical constructions or prose. However, specialist knowledge was involved in compiling these Greek accounting documents. Moreover, we can see the scribes who were supposed to be making these documents practicing key elements.

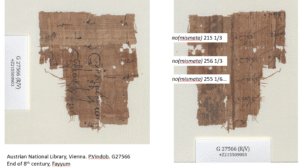

The writing exercise shown below is currently held at the Austrian National Library in Vienna. It was found in the Fayyum region of Egypt. At the end of the nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of papyrus fragments were excavated in Fayyum, sold on the antiquities market, and exported out of Egypt, ending up in collections. The Vienna collection largely has its origins in that context.

This fragment of papyrus shows a scribe practicing, line after line, a heading for a list recording tax collection day by day: “With God; daily register of the collection of taxes in gold of the 13th indiction year 173 under ʿAbd al-Malik b. Salāma, administrator.” This heading included names, numbers, and specific abbreviations that all needed practice.

Another key element of accounting documents were the numerals themselves, and we see this scribe practicing some fractions above his headings. In Egypt, Greek and Arabic accounting from the 8th century onwards used the Greek alphanumerical system to write numbers. In this system, every letter of the Greek alphabet corresponded to a numerical value. To write a fraction, you wrote the corresponding numeral with a diagonal stroke on top. To write 3, you wrote the letter gamma; to write 1/3, you wrote the letter gamma with a diagonal stroke.

Below is another example of a fiscal scribal exercise, a fragment which is also part of the Austrian National Library’s collection and of which I’m preparing an edition. This fragment also comes from Fayyum and can be dated towards the end of the 8th century. This fragment comes from a sheet of papyrus that was most likely used in the fiscal administration, just like the one on the right which I just discussed. It was then reused by a scribe at the office of the district administrator to practice a heading for an account, similar to the example we saw before.

That it was not wholly unnecessary for the scribe to practice his heading is shown by the fact that in the first line, he already forgot an important word of the heading, namely the word “register” itself, “kōdikon.”

On this side of the fragment, we see at least two stages of writing. Before the scribe used it to practice his headings, it was used to write an account, as you can see on the right, where the image is turned 90 degrees to show the direction of the original account. This account records amounts of money, generally between 1 and 9 nomismata or dinar. The dots you see in front of the numerals are originally abbreviations for nomisma, meaning coin or money in Greek. These are relatively low numbers and could refer to individual tax payments of one person.

On the other side, shown here on the right, much higher numbers are recorded, three of which are over 200 nomismata or dinar. We don’t know what kind of payments they record, but it is possible they refer to tax payments of a group of people. These recordings of larger sums make it likely that the account was produced in the context of district administration, in the capital of the district, rather than in a village. We do know that the account at some point was no longer of interest for the administration and was then reused by the scribe to practice this heading.

This kind of reuse of an accounting document raises questions about what we can say about the life of other preserved accounting documents, from looking at what other texts were written on the same piece of papyrus. There are about 200 edited Greek accounting documents that are dated to or have been assigned to the 8th century. The number keeps changing as I go through the documents and editions. This short overview offers a first step in studying the production, use, and reuse of Greek accounting documents.

About half of the 8th-century accounting documents are those found among the papers of the administrator of Aphrodito, Basilios. This is a large, multilingual archive of hundreds of documents from the early 8th century. Among the accounting documents in the archive are several accounting books, with codices consisting of up to 19 folios and over 660 lines of entries. Several scribes could be involved successively in writing these accounts, which contain only those accounts and were clearly kept together for storage as part of the archive.

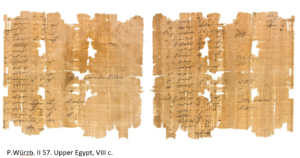

However, this is not the case for all 8th-century Greek accounting documents. Outside of the Basilios archive, we find examples where it seems the same account takes up both sides of the papyrus sheet. This example from the recent P.Wuerzburg II volume records entries related to the land tax and the capitation tax on either side of the papyrus. The editor notes that the texts on both sides present the same arrangement and handwriting, and that one side could have been the continuation of the other, although we can’t say that for certain.

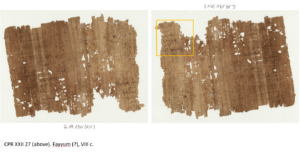

On the other hand, we also have sheets of papyrus that contain an accounting document on one side and a different one on the other. In some cases, these are even edited as two separate, standalone documents, like in the case of CPR XXII 26 and 27, written on either side of a sheet, where the sheet was also turned 90 degrees to write the account on the other side.

Moreover, CPR XXII 27 contains two columns of writing, and to write the second column, the sheet was again turned 180 degrees. It’s not clear whether the two columns on this side are related or not. As Coptologist Vincent Walter suggested to me recently at the International Congress of Papyrologists in Cologne, turning the papyrus and starting a new text at an angle of 90 or 180 degrees seems to have been a common practice in reuse, perhaps to indicate that the separate texts are not related.

So here we have continuous use of the papyrus sheet for accounting purposes in the administrative context, whether for the same account or a different account. In such cases, it is possible that the document maintained its relevance and was kept in storage at the archive of the administrative office, before it was eventually discarded.

However, when we find other types of texts on sheets with accounts, like writing exercises, this signals a repurposing of the papyrus sheet where the accounting document itself likely lost its immediate administrative relevance. In the case of repurposing accounting documents for these administrative writing exercises, the papyrus sheet with the account is retained within the administrative context where it most likely was produced, and given a new purpose before eventually being discarded. An account, however, could also leave the administrative context, as the following example will show.

P.Naqlun II 24 is an accounting document found on the site of the Naqlun monastery, located in the Fayyum district. However, it seems to have originated from a different district. The fragment lists small local tax units or villages from the Ihnas district or the Heracleopolite district in Greek, as well as amounts of money. This is most likely a fragment of a register used and/or produced in an administrative office of the Heracleopolite district. On the other side, however, is a Coptic letter, which has not been edited and of which, unfortunately, the publication does not provide an image. As Nick Gonis proposed, it is likely that the original account, when it was no longer of use in the administrative office, was reused for a letter that was sent to the Naqlun monastery.

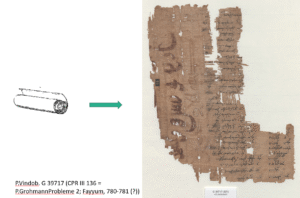

This preliminary research allows us to make some observations on the lifetime of accounting documents. When a scribe needed to write a new account, register, or list, he could take a fresh, blank piece of papyrus. This could very well be the first sheet of a papyrus roll, as we see in the example below, where the Greek account is written alongside the Arabic text of the protocol. A protocol text was written on the first sheet of a papyrus roll and in the late antique and Early Islamic periods contained information under whose authority and where the roll was produced. The Aphrodito accounting books also integrate protocols in their format.

A scribe could also repurpose the blank side of an existing account to write, as we’ve seen in the case of CPR XXII 26 and 27. At some point after the account was drawn up, papyrus sheets with accounting documents could be reused either for accounting purposes within the office, but also for scribal training within the office, or for purposes that seemingly had nothing to do with accounting, and as such, the accounts could leave the context of the administrative office altogether. But not every accounting document was reused: some accounting documents are written on one side of the papyrus, while the other was left blank. Apparently, in those cases, there was never a need or reason to continue the accounting document on the other side or to repurpose the sheet in any way before it was eventually discarded. On the other hand, as Boris Liebrenz kindly reminded me after my presentation at the 35th Deutscher Orientalistentag earlier this week, reuse of documents could entail more than reuse as a writing surface. E.g., the Coptic travel permits found in the monk Frange’s living space in Western Thebes (8th century) were very likely intended for reuse by the monk in his book production activities, as sheets of papyrus glued together could be used as book covers. Depending on our access to certain information, such as the finding context of the accounting documents, this could be a fruitful avenue to explore when examining the lifetime of accounting documents.

Selected sources

Berkes, Lajos. “Greek Documents and their Scribes in Eighth-Century Egypt”, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 65 (2025) 80–98.

Boud’hors, Anne. “L’Apport De Papyrus Postérieurs À La Conquête Arabe Pour La Datation Des Ostraca Coptes De La Tombe Tt29.” In From Al-Andalus to Khurasan, edited by Petra Sijpesteijn, 115–29. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Gonis, Nikolaos. “Reconsidering Some Fiscal Documents from Early Islamic Egypt IV,” ZPE 186 (2013), pp. 272-273.

Greek and Coptic documents are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”. Arabic documents are cited according to “The Checklist of Arabic Documents”.

Banner image: Fiscal accounting document reused for fiscal scribal training. End of 8th century, Fayyum. Austrian National Library, Vienna. P.Vindob. G27566.

This Spotlight was written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply