*** By Alasdair Grant (Universität Hamburg) ***

Let’s begin this post by thinking about what sort of role taxation plays in our lives today. Firstly, tax is something we are required to pay, not something we choose to pay. Having paid it, we might hope for some kind of rebate, either because of work-related expenses or because the government took too much money in the first place. Furthermore, we have probably all complained about what the government does or doesn’t do with our tax money: building schools, training armies, filling potholes. Lastly, there is a general party-political trend when it comes to tax: left-wing governments tax more to spend more, right-wing governments tax less and spend less. The resulting debate centres around questions of public debt, who deserves what services, and how much the state should intervene in our lives.

Overall, then, discussing taxation leads us to engage with a broad range of topics that we might categorise as economic, political and social, while the nature and context of those discussions will take us into matters cultural. Taxation is, at its core, an economic institution, but its ramifications are substantially wider. When studying the past, it can therefore offer us a sort of entry point for analysing both how the state might have worked, and how subjects of that state might have related to it.

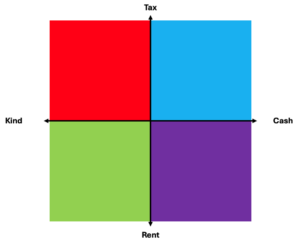

Fig. 1: A Diagrammatic Representation of the Kind/Cash–Tax/Rent Nexus (Image: Author)

This post is built around an image (Figure 1). The image comprises a graphic, based on the diagrams of political orientation that became popular online a few years ago. Instead of an X-axis relating to left- and right-wing politics and a Y-axis relating to authoritarianism and liberalism, we have here instead a diagram built on some key features of historic taxation. The X-axis, this time, reflects the nature of the resources collected: on the one side, kind (more on this term soon); on the other, cash. The Y-Axis, meanwhile, reflects the legal basis of the payments: at the top, reflecting the ‘authoritarian’ end of the familiar spectrum, we find tax; at the bottom, by contrast, we find rent. My argument is that these two spectra between them capture most features of importance in pre-modern taxation. The fact that they are spectra, rather than isolated categories, reflects the fact that most systems before the modern bureaucratic state used a mixture of all four elements.

The X-axis tells us mostly about the effects of taxation upon the payer. If taxation is collected in kind, payments will usually come in one of the following forms: first, and most importantly, crops such as grains, and notably wheat; second, artisanal products, such as textiles or military equipment; third, forced labour; and fourth, in some cases, items of worth that are neither grown nor made, but extracted, such as fish. Within this last category, we may perhaps also include enslaved people, since they were treated as commodities according to their legal status. If taxation is collected in cash, on the other hand, things suddenly become much harder for the taxpayer, and especially for the peasant farmer. The peasant is forced to sell their grain or livestock for cash; this, in turn, necessitates the existence of some sort of cash-flow in the economy, which in practice means trade routes, markets and mints. In both the Roman and Early Islamic empires, this cash was carried in the pockets of a salaried army; the fewer soldiers present, the lower the cash-flow. On the other hand, the fewer soldiers present, the less likely the locals will be forced at sword-point to pay up.

If we turn now to the Y-axis, this tells us more about the state and the power elites that run it, and less about the people they exploit. Here, we are talking about the difference between land that remains subject to the control and taxation of the state, and land that is devolved to members of the power elite. In the latter case, the person with the title to the lands will manage the extraction of resources for themselves. Some of this will be rent; peasants will often pay taxes as well, but these will be under the control of the landlord rather than levied directly by state officials. These privileges, in turn, will come with obligations towards the state, particularly military service. In such a situation, it is to be assumed that inefficiencies and corruption will creep in – at least if we retain the perspective of the state. At the rent-based end of the spectrum is essentially a privatised land economy managed by stakeholders rather than a bureaucracy. Should this stakeholder control become hereditary, as it did in western Europe, it poses a major threat to the integrity of the state. In the Islamicate world, by contrast, such control was not officially hereditary, though dynasties naturally managed nonetheless to dominate particular areas.

Much of Europe and the Middle East moved away from a tax-based state and towards a rent-based state in the ninth to eleventh centuries. Traditionally, this has been called ‘feudalisation’, but the term is so laden with ambiguity and now so beleaguered by opposition among historians that we may wish to discuss the process with other words. A possible explanation for why a state would turn from tax to rent is a crisis in the military budget: if soldiers cannot be paid from the central coffers, they can be raised by those that have the means to do so. The problem is that when these soldiers and their paymasters become too powerful, they become independent of the bureaucracy and perhaps even carve out their own state. Once again, it is worth stressing that tax and rent can and did coexist within the same state; what matters is when and where the balance tips, and what ramifications this has for power relations.

Thinking in terms of kind and cash in parallel with tax and rent allows us to use taxation history as a kind of temperature-check for the state. First, it enables us to evaluate what sort of control a given state had over its resources in a given time and place. Second, it encourages us to think about what that state’s policies meant for the vast and so often invisible peasant majority of the past. Just like the diagram, we can therefore think from the top down, the bottom up, or side-to-side.

Banner image: Dirham of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tamid (870–92 AD) (Cropped), The Portable Antiquities Scheme, Dot Boughton, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0.

Alasdair is a member of the Emmy Noether research group “Social Contexts of Rebellion in the Early Islamic Period (SCORE)” at Hamburg University. Here and here you can read about the “Trouble with Taxation” workshops co-organized by the PI’s of Caliphal Finances and SCORE.

Leave a Reply