As part of my investigation into the heads of the fiscal administration in Abbasid Egypt, I (Postdoc Noëmie Lucas) am trying to establish a complete list of the finance directors from 750 to 969. In previous posts, I shared different aspects of this inquiry, shedding light on a well-documented ṣāḥib al-kharāj, illustrating my work on the papyrological corpus, and presenting new material about a Tulunid finance director. Today, in this blog post, I will share with you a case that is giving me a hard time.

During the caliphate of al-Muʿtaṣim (833-842), the governor over Egypt and the West was Ashīnas. He had the authority to appoint the resident governor. Between 839 and 841, the resident governor was Mālik b. Kaydar, and according to what we read in al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-Wulāt, he did not have responsibility over the kharāj administration (al-Kindī, 195). At the time, from 838 until 842, the ṣāḥib al-kharāj was Abī-l ʿAbbas Saʿīd b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, who is mentioned in about 10 documents, mostly, if not all, tax receipts from al-Ushmunayn.

One of these tax receipts from al-Ushmunayn, CPR XXI 44, dated from 226/841, presents a peculiarity. Not only do we find the mention of Abī-l ʿAbbas Saʿīd b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, but another name, also known to have been ṣāḥib al-kharāj, is mentioned: Abū-l-Wazir Aḥmad b. Khālid.

CPR XXI 44 reads as a double tax receipt in the sense that two different payments (baraʾa) are recorded, and the name of each finance director is associated with one of the payments. Yet, the record of two names of aṣḥāb al-kharāj raises questions about the workings of the fiscal administration leadership at the time of the drafting of the tax receipt. Were there two finance directors operating at the same time? Why was it important to record both names?

Abū-l-Wazir Aḥmad b. Khālid, the other ṣāḥib al-kharāj mentioned in the document, is known to have been responsible for the fiscal administration of Egypt from 841 to 847, mostly during the caliphate of al-Wathiq (842-847). After that, he was appointed wazir in 847-848 at the beginning of the caliphate of al-Mutawakkil. We know that in 234/849, he was still working in the Abbasid administration as the head of the Dīwān zimām al-nafaqāt in Samarra. He fell out of grace and had his properties confiscated.

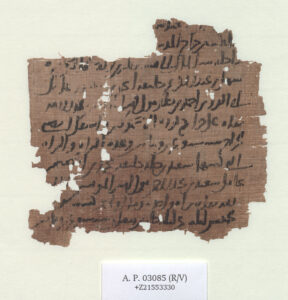

Among the papyrus documents dated to Abū-l-Wazir’s tenure, P. Cair Arab 181, which dates to 847 at the end of his tenure and probably comes from al-Ushmunayn (Grohmann, P Cair Arab III, p. 141), presents a similar setting to that of CPR XXI 44, as two finance directors are mentioned in line 6. Next to Aḥmad b. Khālid, we read al-Walīḍ b. Yaḥyā. They are mentioned together and not alongside as in CPR XXI 44, and the honorific phrase (ʿazzahumā Allāhu – May God exalt them), in the dual form, clearly applies to both of them.

P.Cair.Arab. 181. Image from the edition: Arabic Papyri in the Egyptian Library, ed. A. Grohmann. Cairo. Plate XVI

In his piece devoted to the aṣḥāb al-kharāj in the eighth and ninth centuries according to the documents from Ushmunayn, Aḥmad Kamal hypothesizes that Abū-l-Wazīr was ṣāḥib al-kharāj of Egypt from Baghdad, and Sa‘īd b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān in Egypt, to explain why we find both their names in CPR XXI 44. I wonder whether we should consider another explanation.

I find it worth noting that in both cases studied in this post, the papyrus documents are dated from the end of one’s tenure and the alleged start of the other’s. This might suggest some sort of overlap. In the Caliphal Finances project, Dalia Hussein has been examining the responsibilities of officials with fiscal duties, particularly their obligation to guarantee collection amounts with their own wealth. There is enough evidence in the literary corpus to support this, and I wonder whether this apparent dual leadership indicates overlapping responsibilities, potentially due to a change in personnel mid-fiscal year. In that scenario, it would have been necessary to meticulously record the name of the highest authority in the hierarchy for monitoring processes. This hypothesis is not fully satisfying because we have no reason to believe that the obligation of financial guarantee due from the officials of the fiscal administration, the first of them being the ṣāḥib al-kharāj, was chronologically restricted. Yet, I have not found, so far, other papyrus documents presenting two names of aṣḥāb al-kharāj. Should we consider some singularity of the Ushmunayn corpus here?

I’ll leave it there for this post and hope to have the opportunity to write a follow-up once I have more grounded conclusions.

Arabic documents are cited according to “The Checklist of Arabic Documents”.

Banner Image: Details from Jules Bourgoin, Mosaics of stone in Cairo and Damascus, recorded before 1892 (Beaux-arts de Paris, l’école nationale supérieure, collections, inv : EBA 7901-0304)

This blog post has been written by Noëmie Lucas

Leave a Reply