This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship connected to our research. This week, we feature one of the project’s first guests from May 2022, Dr Harry Munt, a Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of York. During his visit, we spent more than a day discussing Egypt, local histories, and historiographical issues. In the transcript of his interview, Harry notably shares how his research intersects with fiscal matters.

– Could you briefly tell us about your background and career path?

I’m from England. I went to university and studied history, where I started to get into Middle Eastern history. I thought I’d be a modern Middle Eastern historian. But then I started to get very interested in the early Islamic history, and I went on to do masters and doctoral work in that. I did my history degree at Cambridge University, and then I moved to Oxford for my master’s and PhD. I suppose I was quite lucky to apply for those things at a time when the United Kingdom still had a bit of funding for those kinds of studies, and I got funding for it.

My PhD was about, essentially, the same topic as my first book (The Holy City of Medina), that is how Medina became a holy city in the early Islamic period. It starts with a pre-islamic background and the time of the prophet Muhammad. But then it focuses on the second and third centuries, , down to the mid fourth century. I looked at the processes through which ideas about Medina’s sanctity developed over that time, mostly among the ways in which it was promoted as a holy place by caliphs and the people who work for them, but also by Sunni and Shi’i religious scholars, and how they came up with ideas about Medina’s sanctity.

Book cover of The Holy City of Medina

After my PhD, I got a British Academy postdoc, which gave me three years to continue my research and work on turning my thesis into a book and start a new project.

Harry Munt in Nizwa (Oman). Image provided by Harry Munt

– What is your current role, and what does it involve?

I am a lecturer in medieval history at the University of York, where I have been now since 2014. My role involves a fair bit of teaching, research and a certain amount of administrative responsibilities as well, so three aspects of an academic’s role.

I have currently a major administrative role, so I mostly only teach one course for final year undergraduates, which is called “The First Islamic Empire”, on the seventh century. That is a yearlong course that covers the Roman-Persian wars of the early seventh century down to the caliphate of Abd al-Malik. Over the year, we spend a lot of time talking about the primary sources that are available for studying that period.

I also teach on a master’s course on Islamic worlds that is interdisciplinary and shared between a couple of different departments at York. In the past years, I have also taught courses on the Islamic world in the Abbasid period, on Jerusalem in the medieval period, and on the Crusades.

– Can you summarise your main research areas and current projects?

My main research areas are the history of holy places and pilgrimage in the Islamic world. The history of the Arabian Peninsula, particularly the Hijaz but other parts of the Arabian Peninsula as well. Another of my research areas is the history of history writing, down to the 5th/11th century, but also in some cases a bit longer than that. Most of my research, if not all of it, fits into those areas.

Among my current projects, I have just been finishing a book on local history writing that covers the period down to the end of the 5th/11th century, and looks at the ways in which local history was written and what the point of local history writing was in those early Islamic centuries.

I also continue to do little bits and pieces with Arabian history and Hijazi history. I’ve notably been starting to think a about the way in which the Hijaz functioned as part of the early Islamic Empire. Some of that obviously has to do with questions of taxation and governance in the region. I am also getting interested in the environmental history of the region and the role that it played in early Islamic ideas about government and state building in the region.

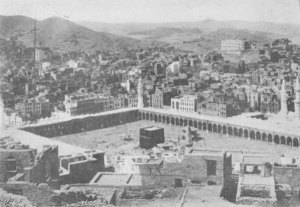

Ka’aba, Mecca, 1909, 山岡光太郎, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaaba_Mecca.png

– What sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

I am writing the book on local histories because the main sources I found myself using to do the other types of history I work on have been local histories, principally of Mecca and Medina, but also of some other regions. A lot of the sources I use for Arabia or the Hijaz are also geographical and topographical. Those are the main kinds of sources I work with unsurprisingly for a region like the Hijaz. There’s very little documentary material to work with for the period I work on. So, it is mostly literary sources and they come with all the issues that using literary sources for the study of early Islamic history comes with.

The sources for the Hijaz are however quite good for certain topics that maybe people haven’t always thought they might be useful for. They are not administrative histories, but they do have some interesting bits of information in them about administrative and fiscal matters and they comprise aspects of governmental histories of the region.

Using those with the more famous chronicles of al-Ṭabarī and al-Yaʿqūbī, you can start to piece together a history of how the region functioned as a part of the early Caliphate, in ways that I was maybe a bit surprised when I started to realize how much material there was for this.

al-Sakhāwī’s al-Iʿlān bi-al-tawbīkh li-man dhamma al-taʾrīkh, Ms. Leiden Or. 677, ff. 78b-79a. http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:2086515, Leiden University Librairies

– How do fiscal theories, practices, and institutions feature in your work? How are you approaching these topics?

They feature mostly in my work on how the Hijaz and other parts of Arabia functioned as part of the early Islamic Empire. Taxation is one of the main ways in which relations between provinces and central governments were mediated. Not by no means the only one, but it’s one of the key ones: money is always important.

The Islamic Empire starts in the Hijaz but then rapidly expands beyond that. Caliphs, obviously, and the central administrations were based elsewhere. I’m mostly interested in questions about taxation, through thinking about why caliphal authorities were still interested in the Hijaz as a province and as a region that they wanted to govern and how they understood the place of the inhabitants of that region within their empire. Taxation is one part of that, but it’s quite an important part. Perhaps I am approaching taxation in a slightly old-fashioned sense of thinking about what the central governing authorities thought they were getting out of this province, and what the inhabitants of that province thought they were getting back from the government in return.

– In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

I think there are many assumptions about fiscal history that we probably don’t actually know that much beyond the assumptions we make. For Arabia,, one of the assumptions I come across that is not quite right is the fact that the Hijaz in particular doesn’t provide a lot of tax revenue for the Caliphate. It is a problematic assumption, not necessarily because it is not true: the region does provide relatively little compared to some other provinces. But I find it questionable assumption on the basis that that’s the only thing that taxation would be important for. Taxation is a form of governance, a form of building governing apparatuses in an area and in a region. And when you think about questions about how nomadic populations are taxed, those are completely intertwined with questions about how submissive nomadic groups are to governing authority. Then you start to see that it is not only about the resources the government can get from taxation. It’s also about the status that some tribal leaders can get from being the people who mediate between the government and their tribes, over revenues and things like that. So, I think that saying that a region like the Hijaz doesn’t provide much money to the Caliphate in terms of taxation sort of misses some of the significance of studying taxation in that province.

A big thank you to Harry Munt for sharing his thoughts with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

Banner image: Prophet’s Mosque, Medina, 1908, Ibrahim Basha, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply