On 10th March, the Caliphal Finances team delivered another lecture in their lecture series “Taxes taxes taxes. All the rest is bullshit in my opinion”. PI Marie Legendre, postdoc Eline Scheerlinck and PhD student Georgi Obatnin joined forces once more to discuss a topic that touches on all of their respective interests within the Caliphal Finances project: accounting and accounts in the fiscal administration. Since Greek numerals play a key role in Abbasid accounting practices, our lecture also turned to the issue of multilingualism.

Georgi Obatnin, Marie Legendre, Eline Scheerlinck at the IMES lecture 10th March. Photo credit Noëmie Lucas.

Marie discussed the research she has done on the so-called language reform under the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik. She challenged the conventional account of a language reform under ʿAbd al-Malik in the early 8th century, which supposedly mandated the replacement of languages like Greek and Middle Persian with Arabic in administration. Instead, Marie argued, drawing on the work of Wadad al-Qadi and her own research, that what occurred was the translation of fiscal registers (dīwān) into Arabic in key provincial capitals. In Basra (Iraq), the translation was from Middle Persian to Arabic, while in Damascus (Syria) and al-Fusṭāṭ (Egypt), it was from Greek to Arabic. The Arabic sources refer to this as naql al-dīwān, and it pertained specifically to fiscal registers, not a comprehensive language reform across all administrative functions. Consequently, Greek and Middle Persian continued to be used in other administrative documents for decades after these translations.

Examples of pre-translation fiscal registers illustrate their nature and scale. A substantial Greek register from 643-644 CE (CPR XXX 1) documents the requisition of building materials for Fustat, highlighting fiscal practices . Another impressive Greek register from Nessana in Palestine (around 685 CE) details army payments in cash and grain. These examples demonstrate the likely format of fiscal records before the Arabic translations.

Following the translation of the dīwān, early Arabic accounts from Egypt, dating back to the Umayyad period, reveal a significant characteristic: while the text was in Arabic, the numerical notations remained in Greek. This practice persisted well into the Abbasid era, as evidenced by examples like P.Ismaïlia 563 (9th century AD) and P.Cair.Arab. IV 377 (901 CE). Contemporary observations from Theophanes (d. 818) and Ibn Khaldūn (d. 808/1406) suggest the continued necessity of non-Muslims in administration due to the reliance on Greek numerals, which were supposedly difficult to represent in Arabic. Ibn Khaldūn noted that accounting remained in the hands of mawlās and dhimmīs.

However, Marie qualified these views, pointing out that the translation of the dīwān also involved a change in personnel at the head of the fiscal administration, with non-Muslim heads being replaced by mawlās. Despite this, the wider provincial administration remained largely staffed by non-Muslims. Marie argued that the continued use of Greek numerals in Arabic accounts suggests that the key characteristic to be a secretary of the fiscal administration was the ability to write both Arabic language and Greek numbers, a skill potentially possessed by both Muslims and non-Muslims.

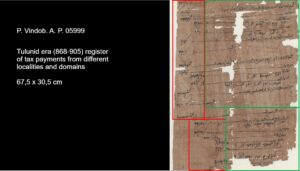

Fiscal accounting document from Abbasid Egypt in Arabic and Greek. Part of the papyrus collection of the Austrian National Library.

Marie also highlighted that accounting culture was regional. Unlike in Egypt, Arabic documents from Khurasan consistently spelled out numbers in full letters, indicating diverse administrative practices across the Abbasid world. Finally, she noted the enduring relevance of numbers as a shared means of communication across linguistic communities in the Abbasid, with Greek numerals serving as a common language understood by literate Egyptians writing in Greek, Coptic, or Arabic.

Eline discussed the continued use of Greek in the fiscal administration of Egypt following the Islamic conquest in the mid-seventh century. While Arabic gradually gained prominence, Greek, which had been an administrative language since the 4th century BCE, persisted alongside Arabic and Coptic, particularly at higher administrative levels.

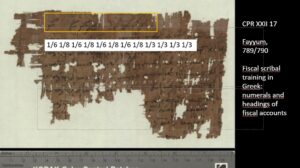

A key point was the persistence of Greek in accounting documents, such as tax receipts, demand letters, registers, and accounts, even into the latter half of the 8th century. Notably, accounting documents are they only attested fiscal documentary genre which could be still written fully in Greek in the later 8th century. Eline suggested that the continued use of Greek numerals in fiscal accounting practice in Egypt was a significant reason for this persistence. Since accounting heavily relied on numerals, and these were rendered in Greek, it was practical to write the rest of the document, which often consisted of personal and place names without complex grammar, but with specific abbreviations, in Greek as well. Examples of scribes practicing headings for lists and Greek fractions highlight the importance of these elements. Eline showed an example of such a scribal exercise: a fragment of papyrus currently held at the Austrian National Library of which she is preparing an edition. On both sides of the fragment amounts of money, down to the very small fractions, are recorded. The small fragment was part of a fiscal accounting document produced most likely at the office of the district administrator in the Fayyum region, which is where the fragment was found. A scribe at the office reused one side of the papyrus to do some scribal training: he practiced a heading that was meant to go above a fiscal account.

Published example of Greek fiscal scribal training in Abbasid Egypt: CPR XXII 17 recto.

Georgi then shared part of his PhD research: the accounting documents presented by Marie and Eline, as well as many fiscal administration records, contain a high number of fractions when recording money: ½, 1/3, ¼, 1/6 of a gold coin (nomisma in Greek, dinar in Arabic), up to 1/24 and even 1/48. Given the practical impossibility of splitting a gold coin of 4.24 grams into 48 pieces (although there is evidence of coins being split), Georgi concluded that the fractions in the accounts must have been referring to a certain value rather than actual gold. An important consequence of this insight for our understanding of the fiscal system is that a tax receipt for, say, 1/2 and 1/12 dinar might not have recorded a payment of gold, or even of any coin at all. Rather, Georgi argued that the fiscal system was quite flexible, and while the documents refer to the value of money, they often actually record payments in different forms, such as credit or goods, like agricultural produce.

Our IMES lecture underscored the complexity and adaptability of the Abbasid fiscal system, which was marked by a rich interplay of languages and numerical practices. These insights into historical accounting illuminate how fiscal documents were not only records of transactions but also reflections of a vibrant, multilingual administrative culture that persisted across centuries.

Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”. Arabic documents are cited according to “The Checklist of Arabic Documents”.

Banner image: golden dinar dated 780 CE, found in Iran, Nishapur. Part of the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Leave a Reply