On 10 February, our colleague Nik Matheou, Lecturer in Medieval Global History at the University of Edinburgh, honoured us by participating in the IMES Seminar Spring 2025 Lecture Series on taxation. In this blog post, our PI, Marie Legendre, shares her reflections on Nik’s paper.

In 1993, Russian anthropologist and historian Anatoly Khazanov published a comparative article on the early Islamic and Chinggisid conquests, focusing on the religious factor in the building of those two world empires. This article still finds its place in the reading list of many university courses and, in my experience, the debates it sketches has often fascinated students of Islamic history. Indeed, the comparison is still meaningful for the 2020s and can be fruitfully expanded to other factors. The fiscal policies implemented by both conquering empires show interesting echoes. Those echoes prompt us to go beyond listing the obvious similarities or differences and to asking question from our material that we wouldn’t think of if we had not attempted this comparative exercise between two key moments in the history of Eurasia.

The Caliphal Finances team had the opportunity to reflect on this comparison as Nik Matheou presented his ongoing research in the seminar of the department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies on Monday 10th of February 2025. He presented his work on the Chinggisid world order from the point of view of the Armenian city of Ani, to the north of the Ilkhanid sphere. Ani was a commercial centre known for the production of ceramics and textiles (silk and cotton), hardly a remote frontier location as the city served as a halt for the Ilkhans on their summer-winter progression between pastures.

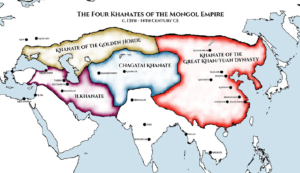

Map of the four Khanates of the Mongol Empire, after its division in 1259 CE. Credit: Arienne King, (CC BY-NC-SA)

In light of Nik Matheou’s paper at the seminar, a few of the parallels between the fiscal history of the early Caliphate and the Chinggisid empire can be stressed here: the efficiency of their fiscal administration and the ensuing trauma memorialized by local elites, the necessary reliance on local powerbrokers and the creation of new elites within the establishment of a new administrative and fiscal order (the ortoqs – ortaghda – of Chinggisid Ani or the mawālī of the early Islamic world). The efficiency and rapidity of the implementation of the new order in the aftermath of conquest is visible in the introduction of new units of tax assessment (tümen in Chinggisid Ani, chorion in early Islamic Egypt) and of a capitation tax paid in cash. It is a common argument that the implementation of a capitation tax is a quick way for a conquering power to collect cash. The focus on local elites shows how much the new world created by each of those world empires were a co-production between locals and the new ruling elites as argued by Annliese Nef in Révolutions Islamiques. References to upheavals in South Caucasia against Chinggisid taxation in the second half of the 13th century is a window into the negotiations within the new system that echoes the revolts punctuating the first centuries of Islamic rule.

Additionally, Nik Matheou’s research shows that narratives of reforms and their purported success under Ghazan do not find confirmation in the local documentation. Similar claims of reforms and their success under the Marwanids or early Abbasids comes to mind with comparable difficulties when trying to confirm that in the detailed fiscal documentation of the time. This prompts us to questions whether such narratives sit within a wider discourse about governance expressed by a self-confident ruling elite.

We often count ourselves lucky to work on papyrus documents from early Islamic Egypt because of their sheer number and because of the wealth of information that can be gleaned from their study. It is however clear that fiscal questions can be studied in many other regions of the Islamicate world based on a diverse primary material. More than a hundred inscriptions survive from the city of Ani dating to the long 13th century, mostly preserved on the walls of churches, and some of them copying documents issued by Ilkhanid administration. A few examples stand out as they comment on patterns in the economic trajectory of the region under Ilkhanid rule. They speak to the sudden transformation in power relations between members of the elite now increasingly connected to Ilkhanid fiscal administration, and those left on the outside. This is both a result of the political power provided by administrative offices, and the financial power created by access to new sources of revenue while others wilted under increased tax burdens – a Georgian document of 1259, and an Armenian inscription of 1283, both talk of times when ‘money was rare and land cheap’, while a 1331 Persian inscription in Ani complains that both elite and subaltern actors were leaving because of heavy taxation.

Finally, Nik Matheou’s research cements the place of the Caucasus and its sources in a variety of languages as internal perspectives essential to a proper understanding of Islamicate history, as famously championed by Alison Vacca for the early Islamic period.

It is a great chance for our team to have a close colleague in the same university equally passionate about the study of Medieval taxation and we are looking forward to continuing our conversations with Nik Matheou on taxes and empire!

** This post was written by PI, Marie Legendre **

Banner Image:Late-12th/early 13th c. Facade of the Church of the Holy Apostles (Surb Arak’eloc’) with Tax Inscriptions of the Ilkhanid Period – Dosseman, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Leave a Reply