In my search for Coptic and Greek fiscal documents from Abbasid Egypt, I (Eline Scheerlinck) came across a curious ninth-century document from the monastery of Apa Apollo in Bawit (P.LouvreBawit 7). The document is of interest for various reasons, but in this post, I want to focus on the fact that it contains fiscal terminology that is out of the ordinary. At the end, I’ll present a little non-fiscal treat—but it will only make sense after reading the rest of the post!

One of the misconceptions about the Abbasid fiscal system that the Caliphal Finances project aims to dispel is that it rested solely on land tax (kharaj) and capitation tax (jizya). In Work Package 3: “Beyond jizya and kharaj: A nomenclature of all attested taxes in Abbasid Egypt, their weight for taxpayers, and their place in the fiscal collection,” we aim to bring together evidence from the multilingual corpus of fiscal documents demonstrating the diversity of taxes collected in the Abbasid period.

A Fiscal Document Sealed with the Seal of the Monastery

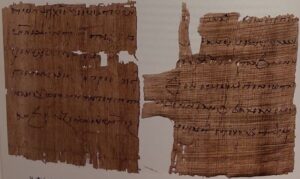

P.LouvreBawit 7. Image from the edition: Papyrus grecs et coptes de Baouît conservés au Musée du Louvre, ed. †S. J. Clackson and A. Delattre. Cairo 2014 (Bibliothèque d’Études coptes 22), p. 14.

As an example of work-in-progress in this aspect of our research, let’s consider the fiscal term stichoi, which I found in Greek and Coptic fiscal documents dated to the Abbasid period, including P.LouvreBawit 7. This Coptic document, dated to the ninth century based on palaeographical grounds, survives in two fragments held in the papyrus collections of the Musée du Louvre. These fragments form the last six lines of the document. Only the left and bottom margins are complete, which means that we are missing the beginning of the text as well as parts of each line. Unfortunately, this also means that the exact meaning and function of this document are not fully clear to us—a challenge we often encounter when working with documents. The document uses phrases and expressions reminiscent of contracts and appears to have been connected directly to the administration of the monastery, as it mentions in the last line that it was sealed with the seal of the monastery. The seal itself has not been preserved.

Stichoi: Part of Early Islamic Greek Fiscal Terminology

The first and second lines of (what remains of) the document are of particular interest. The first line starts in the middle of a sentence whose beginning is lost: “(l. 1) …and the stichoi: see, what is in the…monastery, and see, the… (l. 2) … of the dēmosia of this (number lost) year of the indiction…”. The term dēmosia, used here in the plural, is understood as taxes collected or assessed in cash. In contrast to stichoi, it is a commonly found fiscal term in Greek and Coptic papyri and warrants its own discussion.

The Greek stichoi, which in literary contexts meant “verses” or “lines,” was used as a fiscal term in the post-conquest administration of Egypt from at least the early eighth century. From its attestations in Greek in the early eighth century, we understand that the term generally meant “imposts,” often described with adjectives such as “other,” “remaining,” or “various” and recorded alongside more defined categories such as dēmosia and diagrafon (capitation tax). However, five individual tax receipts have been edited that record a stichoi tax paid in the years 726–727 in a village in the Theban area in southern Egypt. Interestingly, stichoi was the only tax mentioned, and the amount paid was the same in each receipt. Could the stichoi have been a more specific tax or some form of extraordinary impost in this case?

Stichoi in Abbasid Fiscal Documents

CPR XXII 22 verso. Abbasid fiscal accounting document in the collection of the Austrian National Library Vienna (G 19115)

P.LouvreBawit 7 shows that this Greek fiscal terminology continued into the Abbasid period in Coptic administrative texts produced in large monasteries, which, as Cecilia Palombo has shown, were highly involved in the province’s fiscal administration. Another example of stichoi used as fiscal terminology in an Abbasid fiscal document is the Greek fiscal accounting document CPR XXII 22. This accounting document records taxes claimed for the years 158 and 159 (774–776 CE). One column records tax payments made in cash for arrears in the embolē or grain tax, and the second column records tax payments “levied for the price of various imposts” (anusthenta huper timēs diaforōn stichōn). Thus, the Greek accounting and recording practices of the Abbasid fiscal system, as seen in Umayyad documents, sometimes allowed for some generalisation and vagueness; it was not always necessary to specify precisely which type of tax was recorded, and a term existed to group “other” taxes.

P.S.

The term stichoi itself also evokes an image of taxes being recorded line by line in an accounting document. The meaning of stichos as “line” or “verse” in literature was still in use in eighth-century Coptic, as seen in this amusing letter from the area near Luxor on the opposite bank of the Nile (O.Frange 654): “I sent eight pomegranates and a bit of lemon with Kēr(…). Be well, my beloved venerable fathers in the Lord.

Tnadnuba si taht setad fo tnuoma na em tnes uoY.

Don’t think that this line of writing (peisdichos nshai) is an alphabet. No, it goes like a wheel. Study it in that manner.” This fun bit of wordplay – the line (or stichos) can be read backward like a wheel can roll backwards – serves as a reminder that people had other thoughts besides taxes to occupy their minds and lives.

The diversity of taxes and tributes in Abbasid fiscal practice is also discussed here and here.

Coptic and Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”.

Banner image: The Nile from Luxor. Image by Marek Kocjan, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply