We would like to shine a light on one financial director (ṣāḥib al-kharāj) of Egypt during the Abbasid period who is known to us from various sources. An overall aim of the Caliphal Finances project is to study all the actors involved in fiscal collection from the taxpayer to the caliph, including the participation of local administrators and elites in the shaping of fiscal policies. We are particularly interested in the fiscal administrative hierarchy. Noëmie Lucas (WP4 Making the Link: Fiscal Practice and the Literary Corpus) is working on gaining a clearer view of the upper-level administrators who are better documented in the literary corpus than the local ones.

Al-Khaṣīb ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd is one of these aṣḥāb al-kharāj who operated in Egypt for the Abbasids in the early ninth century. He is documented in both literature and material culture and will be the focus of this blog post.

In the Abbasid period, the governor was in charge of the administration of region. Among his prerogatives were the army, the handling of the regional administration, and, not systematically, the control over the fiscal administration. The latter was monitored and managed by a finance director (ṣāḥib al-kharāj) who, when he was not the governor, was appointed separately by the caliph and was often an outsider to the Egyptian province (Kennedy, 1981). Al-Khaṣīb ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd was one such ṣāḥib al-kharāj who was not governor.

Al-Khaṣīb b. ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd in the literary corpus

We do not know the exact date of his appointment in Egypt, but we can say that it occurred sometime after the demise of the Barmakids (in 187/803). Al-Jahshiyārī, in his Kitāb al-Wuzarāʾ wa-l-kuttāb (254/321), reports that Caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd wanted to appoint individuals who had not been working with the Barmakids, and al-Khaṣīb b. ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd was one of them. He is said to have been appointed over Egypt and his estates (وولى الخصيب ابن عبد الحميد مصر وضياعها). In this context, we can argue that this means he was appointed at the head of the fiscal administration and not the governorship.

We also know that in 187/802-803, the governor of Egypt, who was also in charge of the fiscal administration, al-Layth b. Faḍl, lost the prerogatives of the fiscal administration to Maḥfūẓ b. al-Sulaymān in the context of a fiscal revolt in the Delta (al-Kindī: 140-141). So we can assume that al-Khaṣīb was not appointed before 803 at the earliest.

An important aspect of the reign of Hārūn al-Rashīd (170-193/786-809) is that it witnessed the highest turnover of governors in the first decades of Abbasid rule (22 governors of Egypt in 23 years of reign). Therefore, reconstructing the list of officials appointed in Egypt during this specific period can prove to be a difficult task. Be that as it may, let’s see how the rest of the evidence we have at our disposal allows us to pinpoint the tenure of al-Khaṣīb ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd in Egypt.

Our primary Egyptian source for the history of governors, the Kitāb al-Wulāt by al-Kindī (d. 350/969), does not record his name, but it is most likely that we have an indirect reference to him in a poem of Saʿīd b. ʿUfayr (146-226/763-840), a transmitter and poet who is a major source for al-Kindī for the period of his lifetime (Bouderbala, 2008). In the entry devoted to al-Husayn b. Jamīl, governor of Egypt between 190-192/807-808 (al-Kindī, 142), some defamatory verses refer to a ṣāḥib ʿala kharāj, sawādī min al-Akkar, which translates to ṣāḥib al-kharāj, a blacklander of the farmers (translation of Sprengling, 1935, 227). This means that al-Khaṣīb was from Iraq and implies that he came from a low social condition. Al-Khaṣīb ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd’s family was actually from north of Basra, which concurs with this verse (Sprengling, 1935). If we are to follow al-Kindī, al-Khaṣīb must have already been ṣāḥib al-kharāj when al-Husayn b. Jamīl was appointed over the governorate of Egypt, since he was not appointed over the fiscal administration. At some point during his governorship (in 7 Rajab 191/May 807), al-Husayn b. Jamīl is said to have also controlled the fiscal administration, which would mark the end of al-Khaṣīb’s tenure. It is then likely that al-Khaṣīb was ṣāḥib al-kharāj of Egypt between 803 at the earliest, to May 807.

Later narrative sources also report that al-Khaṣīb ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd held a position in Egypt and they agree that he was ṣāḥib al-kharāj (al-Safadi, Kitāb al-Wāfī al-Wafayāt or al-Maqrizī, Khiṭaṭ), but they do not specify the dates.

Material evidence about al-Khaṣīb b. ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd’s administration in Egypt

Material evidence at our disposal confirms that al-Khaṣīb played a role in the fiscal administration of Egypt and provides extra details on his functions as ṣāḥib al-kharāj. Thanks to the work of P. Balog, we know that the name al-Khaṣīb b. ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd has been found on weights, and therefore he must have had responsibilities over checking the weight of coins in circulation, particularly those used to pay taxes. P. Balog, in his catalogue Umayyad, ‘Ābbasid, and Tūlūnid Glass Weights and Vessel Stamps, records two weights bearing the name of al-Khaṣīb (n. 633 and n. 634).

- 633. RAṬL KABĪR Round impression at top, 29:

- مما امر به الامير الخصيب بن عبد الحميد ابقاه الله على يدي مكرم بن خلد

- Among those things which ordered the amīr al-Khaṣīb b. ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd, may Allāh preserve him. At the hands of Mukarram b. Khālid.

- Second round stamp, 18, on the right shoulder:

- رطل كبير واف

- Full weight. Raṭl kābīr

- 634. UNCERTAIN WEIGHT, probably ONE AND ONE-HALF WUQIYYA, Round disk weight with thick rim, about one-third missing:

- مما (امر به الا)مير الخصيب بن عبد الحميد اكرمه الله على يدي مكرم بن خالد

- Among those (things which ordered the a)mīr al-Khaṣīb b. ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd, may Allāh be generous to him. At the hands of Mukarram b. Khālid.

On both weights, the name of another official is recorded, Mukarram b. Khālid. He seems to have been the one actually in charge of checking the weight of the coins for al-Khaṣīb. He is, in any case, working under the authority of al-Khaṣīb.

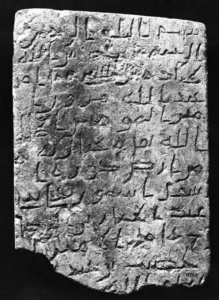

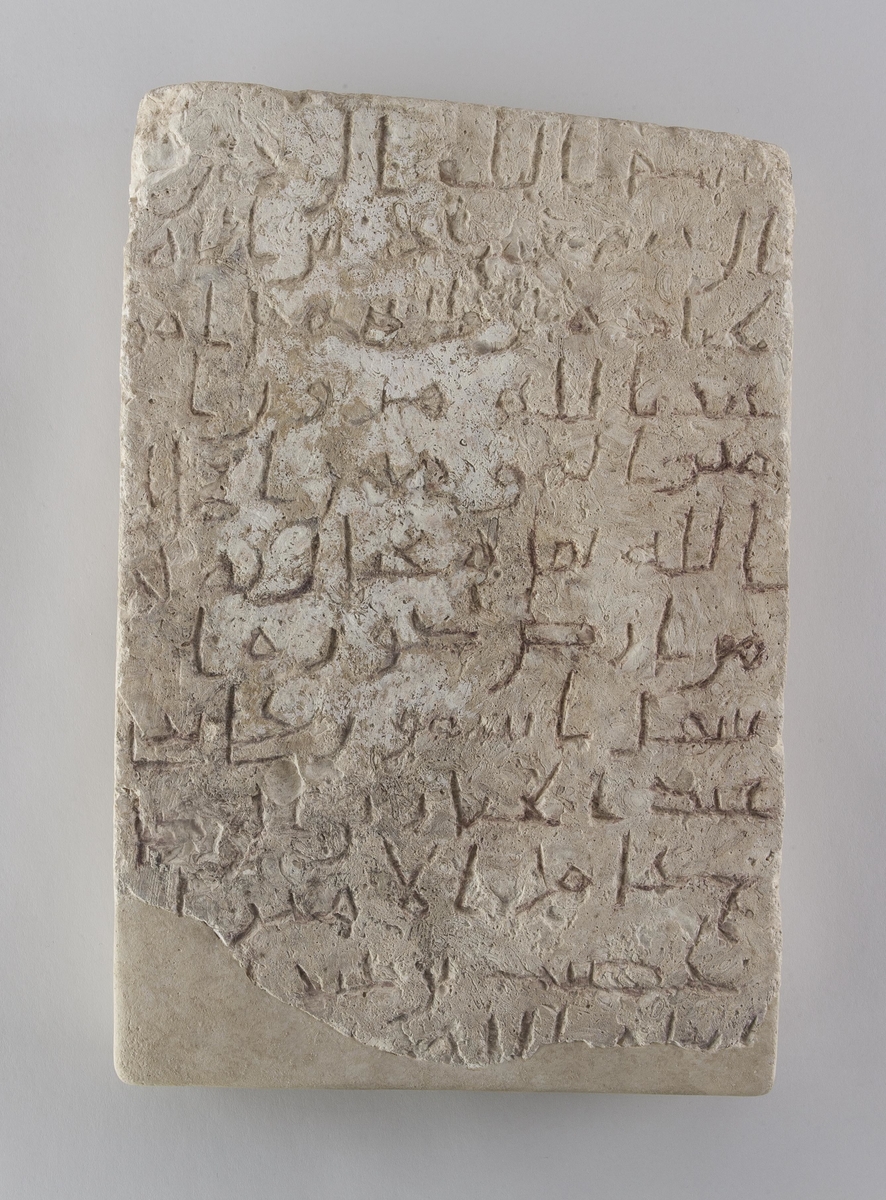

Archival photo of the land stela (P. 20141/N. 11336)

There is another piece of material evidence that mentions al-Khaṣīb and constitutes another material evidence of his role in the Egyptian administration. This inscription also records the name of one of the executives (ʿummāl) working under his authority: ʿAbd al-Jabbār ibn Waddāḥ. The stela is kept at the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures at the University of Chicago and has been purchased from B. Moritz in 1929. Its provenance is unknown, but it possibly came from Minya in Egypt and the inscription refers to Ashmunayn. The stone has been first interpreted as a boundary marker (Randall, 1933) and then Sprengling argued that the stela was erected in the context of a land survey conducted during the reign of Hārūn al-Rashīd (Sprengling, 1935). This interpretation is not certain as the text, even if we accept the transcription, might be translated differently from Sprengling. He reads:

/ مما امر/ عبد الله هرون ا/مير المومنين اطال/ الله بقاءه بحيازته له من ارض كورة ا/سفل اشمون على يدى/ عبد الجبار بن الوضا/ح عامل الامير ا/لخصيب بن عبد

Which I translate as:

“What ʿAbd Allāh Harun, the Commander of the Faithful, may God prolong his stay, ordered to be taken possession for him of the land of the district of Lower-Ashmun by ʿAbd al-Jabbār b. al-Waḍāḥ executive of the ṣāḥib al-Kharāj al-Khaṣīb b. ʿAbd…”

The interpretation of this stela remains open to discussion and it is part of our current investigation to shed light on what this stela might have been. For now, we want to highlight the names present on it that confirm the role of al-Khaṣīb in Egypt as amīr, here referring to the ṣāḥib al-kharāj. The term amīr in documents, be they papyri, coins, or here stele, could equally refer to the governor or the ṣāḥib al-kharāj, and in this case, the rest of the evidence supports the interpretation of ṣāḥib al-kharāj.

Interestingly, these pieces of evidence, the weights and this stela, not only inform us about al-Khaṣīb, confirming his role in Egypt at a high level in the administration, but they also provide glimpses of the administrative network by mentioning these executives working under his authority.

Conclusion

Al-Khaṣīb ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd may not have been a particularly significant or influential financial director in ninth-century Egypt. Our sources do not allow us to make such a conclusion. However, his documented role, evidenced through literary sources and material culture, highlights his function and the intricate administrative network under his authority. Other financial directors were less fortunate and are known only through brief mentions in narrative sources or single papyrus documents. Some retain historical memory due to their association with fiscal history, but they are not necessarily as diversely documented as al-Khaṣīb.

This blog post aimed to spotlight the type of work involved in reconstructing the list of financial directors of the Abbasid period and the type of information we can access. While we may not always obtain exact dates or a clear picture of the events these administrators were involved in, we gather sufficient material to place them within a timeline, a historical context, and an administrative network.

Bibliography

- Balog, Paul, Umayyad, ʿĀbbasid and Ṭūlunid glass weights and vessel stamps, Numismatic studies, 13, New York: American Numismatic Society, 1976.

- Bouderbala, Sobhi, Jund Miṣr : Étude de l’administration militaire dans l’Égypte des débuts de l’Islam (642-833), Thèse de doctorat en histoire, sous la direction de Madame le Professeur Françoise Micheau, Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2008.

- Kennedy, Hugh, “Central government and provincial élites in the early ‘Abbasid Caliphate”, BSOAS, 44, 1981, pp. 26-38.

-

Randall, William R. “Three Engraved Stones from the Moritz Collection at the University of Chicago.” in The Macdonald Presentation Volume: A Tribute to Duncan Black Macdonald, Consisting of Articles by Former Students, Presented to Him on His Seventieth Birthday, April 9, 1933, by MacDonald, Duncan B., 327–330. edited by Shellabear, William G., 327–330. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1933. See: pp. 327-328.

- Sprengling, M, “The Arabian Nights Stone of the Oriental Institute.” in The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 1935, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 217-232.

-

Vorderstrasse, Tasha and Treptow, Tanya, eds. A Cosmopolitan City: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Old Cairo. Oriental Institute Museum Publications 38. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2015. See: pp. 151–152, no. 25

Banner Image: Stable URL: https://isac-idb.uchicago.edu/id/c356e901-15e9-4a38-a4d4-79ab4d0e6a49

This post has been written by Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply