An important part of the Abbasid fiscal documents on papyrus are lists, accounts, and registers written in Greek, as well as exercises in which scribes are practicing Greek phrases and numerals to use in fiscal documents. We are publishing this post, written by our postdoc Eline Scheerlinck, in the context of our ongoing research into two related themes connected to the Abbasid fiscal system: the multilingual nature of the Abbasid fiscal administration and culture of accounting in the Abbasid period.

Greek was introduced in Egypt as a language of administration in the 4th century BCE, when the region became part of Alexander the Great’s conquered territories and subsequently under the rule of the Ptolemaic dynasty, descendants of one of Alexander’s generals. Greek continued to be used as an administrative language throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods and was employed alongside Arabic in the chancelleries of the Umayyad governors in Fustat. By that time, the provincial fiscal administration operated in Arabic, Greek, and Coptic. Greek was used for various types of fiscal documents, such as tax receipts, tax demand notes, and registers and accounts.

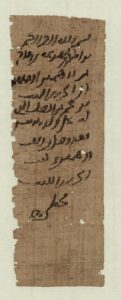

P.Clackson 46, a Greek tax receipt (758), on the back of a tax demand note (P.Clackson 45, 753). Cambridge University Library. Image from the publication: Monastic Estates in Late Antique and Early Islamic Egypt. Ostraca, Papyri, and Essays in Memory of Sarah Clackson, ed. A. Boud’hors, J. Clackson, C. Louis, and P. Sijpesteijn (Am.Stud.Pap. XLVI), Cincinnati 2009.

In the early Abbasid period, these documents could still be written entirely in Greek. For example, tax receipt P.Clackson 46 (758), and tax demand note CPR XXII 7 (a model for a tax demand note, 751, mentioned in our post on the paperwork of taxation). The Greek fiscal documents of the later 8th century, however, take the form of variegated lists, registers, and accounts, while other types of fiscal documents are being written in Arabic and Coptic. Although registers, lists, and accounts were also written in Arabic and Coptic, Greek persisted in these types of documents until the end of the 8th century.

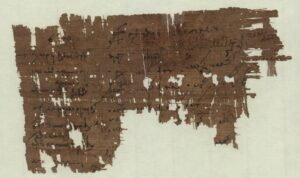

P.GrohmannWirtsch. 12, an Arabic receipt with the number 260 in Hindu-Arabic numerals at the bottom. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

One important reason for the persistence of Greek in these lists, accounts, and registers is that numerals constituted the majority of the content. The distinctions between fiscal accounts, lists, or registers, even if definable, are not the focus here. Most importantly, these documents prominently featured numbers, including fractions, along with specific jargon and many abbreviations. The Greek method of writing numerals, had been useful for Egypt’s new rulers and administration after the conquest. Marie Legendre and Petra Sijpesteijn have recently discussed the language policies and the dynamic multilingual landscape of the Umayyad caliphate across different regions, particularly in Egypt. Greek numerals embedded in texts written in Coptic and Arabic continued to be used for centuries after the 8th century, even though there are exceptional instances of Hindu-Arabic numerals in the papyri in possibly the second half of the 9th century: a document shows the number 260 written in Hindu-Arabic numerals, which has been interpreted as the year 260 Hijri, though this interpretation is uncertain. Generally, numerals continued to be written using Greek letters with long diagonal strokes to indicate fractions.

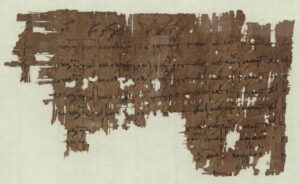

CPR XXII 17: Greek fiscal account with writing practice in Greek, Coptic, and Arabic. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

Compiling a fiscal list or register required specific scribal training, evidence of which can be found in the papyri. One of the most well-known examples is CPR XXII 17, a fiscal account dated to around 789/790, which records payments made by taxpayers from a certain village. The account records payments for two different types of taxes. Some time after the account was compiled, the scribe reused the piece of papyrus to practice the Greek heading of a fiscal account: turning the sheet of papyrus over, he wrote the same heading six times. Below that and in the margins, he practised names and fractions. On the side of the papyrus with the original account, the scribe wrote fractions in the margins and between the lines and repeated some of the names of the taxpayers between the lines. It has been argued that the same scribe also wrote the few Coptic and Arabic epistolary and documentary formulae that were written mostly in the top margin above the fiscal account.

CPR XXII 17 (verso): writing practice of Greek fiscal account heading and other words and numerals. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

In conclusion, our ongoing research highlights the intricate multilingual and accounting practices of the Abbasid fiscal administration, underscoring the persistence of Greek in administrative contexts well into the 8th century. This multilingualism reflects the adaptability and complexity of the Abbasid bureaucratic system, which effectively integrated diverse linguistic traditions to manage and record fiscal activities. Furthermore, the education and training of scribes played a crucial role in maintaining these practices, ensuring the accuracy and efficiency of the fiscal administration.

Selected bibliography

Berkes, Lajos, and Khaled M. Younes. “A Trilingual Scribe from Abbasid Egypt? A Note on CPR XXII 17.” Archiv Für Papyrusforschung Und Verwandte Gebiete 58, no. 1 (January 2012): 97–100.

Legendre, Marie. “The Translation of the Dīwān and the Making of the Marwanid ‘Language Reform’. Secretarial Agency, Economic Incentives, and Regional Dynamics in the Umayyad State.” In Navigating Language in the Early Islamic World, edited by Antoine Borrut, Manuela Ceballos, and Alison M. Vacca, 89–165. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance 2. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 2024.

Sijpesteijn, P.M. “The Early Islamic Empire’s Policy of Multilingual Governance.” In Navigating Language in the Early Islamic World. Multilingualism and Language Change in the First Centuries of Islam, edited by Antoine Borrut, Manuela Ceballos, and Alison Vacca, 43–88. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance 2. Turnhout: Brepols, 2024.

Greek documents in this post are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”. Arabic documents are cited according to “The Checklist of Arabic Documents”. Banner image credit: Marie Legendre.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply