We would like to shine a spotlight on a tax receipt from 10th century Egypt which we mentioned in our post on the Paperwork of Taxation: Abbasid Fiscal Documents from Egypt, but which has not received much scholarly attention. It documents, in a combination of 3 languages, a father paying taxes for his son. The multilingual landscape of the Abbasid fiscal administration is of special interest to our postdoc Eline Scheerlinck, who wrote this post.

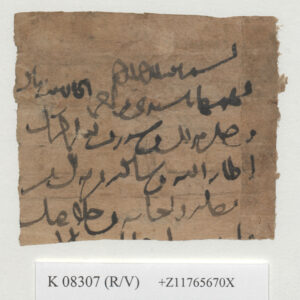

The tax receipt (CPR IV 13) is part of the collection of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna. The standard edition for this document was made by Walter Till in 1958. This is a paper document, and it is internally dated to the year 331 AH, or 942 CE. The tax receipt is written on the back of a letter, of which the first lines in Arabic have been preserved. The letter was then cut and reused to write the tax receipt on the back.

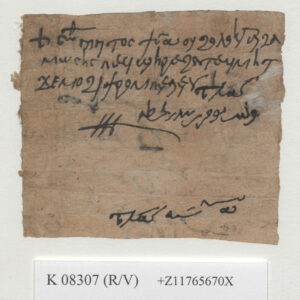

CPR 4 13, a tax receipt for Paitos, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien, K 08307

“+ With God. Paitos gave me one nomisma, one holokottinos (gold coin) for Moses, his son, for the strangers tax of this year that is the year 331. Buqīr (?), son of Theodore, wrote with his own hand +++ 1 Tubi, year 331.”

The first three lines of the tax receipt were written in Coptic: Paitos paid 1 gold coin, on behalf of his son Moses, for a tax named the “strangers’ tax,” for the year 331. In Arabic, the tax collector then signed the receipt with his name and three crosses. At the bottom of the receipt, he wrote the date, again in Arabic. I will discuss two ways in which this tax receipt immediately helps us start to understand the issues the Caliphal Finances project is tackling.

Back of the tax receipt for Paitos: the Arabic letter first written on the paper, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien, K 08307

One of the objectives of the project is to study the multilingual nature of the Abbasid administration. This document is an excellent example of how multilingual the fiscal administration of Abbasid Egypt still was in the mid-10th century. The whole tax receipt is written by the same person. Usually, it is difficult to compare handwriting in two different scripts, but here we can compare the numerals with which the date was written both in the Coptic and the Arabic parts. Multilingual Abbasid scribes are known in Egypt since the late 8th century. Khaled Younes and Lajos Berkes have shown that one scribe practiced numerals, names, and formulas in Greek, Coptic, and Arabic on a reused fiscal register from the end of the 8th century.

In our tax receipt, the more narrative part of the document is written in Coptic, and the signature and the date are written in Arabic. The language distribution in this tax receipt is similar, if not completely parallel, to the early Islamic bilingual Coptic-Greek tax receipts, in which the narrative part of the document would be written in Coptic, and the date, signature, as well as some other elements, in Greek. Those different functions of Coptic and Greek in 8th century multilingual fiscal documents have been studied by scholars like Sebastian Richter and Jennifer Cromwell.

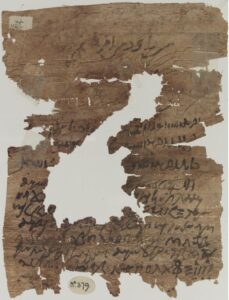

Patterns of language distribution: Arabic and Coptic in a private letter from the 9th or 10th century. P.Ryl.Copt. 379 verso. John Rylands Library, Manchester

The language distribution in this tax receipt is also comparable to contemporary 9th and 10th century private letters as the one in the image above. In some letters of this period the body was written in Coptic, but more formulaic parts opening and closing the letters, as well as the address, were written in Arabic. This language distribution has been associated by Delattre and others with the status of Arabic in Egypt by that time, as the language of prestige and communication. The linguistic puzzle of our tax receipt is made yet more multilingual by Greek elements such as the formula “with God” which opens it. This formula also occurs in multilingual Coptic letters from the 9th and 10th centuries. To understand patterns of linguistic distribution in Abbasid fiscal documents, therefore, it is helpful to compare them with contemporary and Umayyad fiscal documents, but also with contemporary documents across documentary genres.

The Caliphal Finances project also aims to challenge the model of a unified Abbasid tax system in which poll tax and land tax are the two pillars. This tax receipt, as a product of fiscal practice at a specific moment in Egypt, provides evidence of the diversity of that fiscal practice. It gives us an attestation of a specific tax, including its rate, levied at the time. The Coptic word can be seen as the Coptic equivalent of a tax term in Greek: the xenion. We know this xenion from Greek and Coptic fiscal documents dated in the Umayyad period. Some scholars maintain it was meant for the maintenance of Arab-Muslim officials, because of the occurrence of the fiscal term “xenion of the amir” in the documents. It has also been suggested that the xenion was a tax related to “strangers” in the sense of people living outside of their district. While the nature of the tax is unclear, this tax receipt does provide us with a technical term in Coptic which is not related to either poll tax or land tax.

This fascinating document thus illuminates the complex and multilingual nature of Abbasid fiscal administration and challenges simplified models of their tax system. It underscores the importance of examining diverse sources to gain a comprehensive understanding of historical fiscal practices.

Banner image: Pieter Breughel the Younger, The Tax Collector’s Office (c. 1615), Art Gallery of South Australia.

Coptic documents are cited according to the “Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic, and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca, and Tablets”.

This post has been written by Eline Scheerlinck.

Leave a Reply