The teaching of the Middle East at Edinburgh has been strongly influenced by the orientalist preoccupations of language, literature and religious writings, framed by close attention to linguistic analysis and the intensive reading of religious and literary texts. Written translation both in and out of the target language was given priority, with much less concern for the spoken language. Grammar books and prescribed readings drew heavily on the continental philological tradition, something which Edinburgh teachers had experienced themselves at first hand. Indeed, as the University Calendar made clear to prospective students: ‘a working knowledge of German is indispensable for the advanced study of the Semitic Languages’.

At the end of the nineteenth-century the grammars of Albert Socin, Professor of Oriental Languages at the University of Leipzig, translated into English by Archibald Kennedy, and of Carl Paul Caspari, translated and substantially rewritten in a 3rd edition by St Andrews-educated William Wright, served as the authorities on the morphology and syntax of the language. These were used in conjunction with set readings drawn from a number of chrestomathies (selected readers) such Goerg Jacob’s Bible Chrestomathy (Berlin, 1888) and Brünnow’s Chrestomathy of Arabic Prose Pieces (1895). The religious texts focused on the Quran, where students were referred to Flügel’s recently reissued edition (1893), but also included David Margoliouth’s Chrestomathia Baidawiana (1895) and the Delectus Veterum Carminum Arabicorum (1890), a collection of Arabic poetry edited by Nöldeke and Müller. The debt to the German academic tradition and its emphasis on religious texts and classical literature was made even clearer when Theodore Nöldeke (1836-1930), Professor of Semitic Languages at the University of Strasbourg, was awarded a Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) by the University of Edinburgh in 1892.

At the end of the nineteenth-century the grammars of Albert Socin, Professor of Oriental Languages at the University of Leipzig, translated into English by Archibald Kennedy, and of Carl Paul Caspari, translated and substantially rewritten in a 3rd edition by St Andrews-educated William Wright, served as the authorities on the morphology and syntax of the language. These were used in conjunction with set readings drawn from a number of chrestomathies (selected readers) such Goerg Jacob’s Bible Chrestomathy (Berlin, 1888) and Brünnow’s Chrestomathy of Arabic Prose Pieces (1895). The religious texts focused on the Quran, where students were referred to Flügel’s recently reissued edition (1893), but also included David Margoliouth’s Chrestomathia Baidawiana (1895) and the Delectus Veterum Carminum Arabicorum (1890), a collection of Arabic poetry edited by Nöldeke and Müller. The debt to the German academic tradition and its emphasis on religious texts and classical literature was made even clearer when Theodore Nöldeke (1836-1930), Professor of Semitic Languages at the University of Strasbourg, was awarded a Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) by the University of Edinburgh in 1892.

This menu of texts began to change during the 1920s. The foundational writings of the Quran and the Hadith collection Sahih of al-Bukhari, along with the commentaries of al-Baidawi, remained central (although in time they would be replaced by the works of Richard Bell and Montgomery Watt in the field of Quranic studies) but the Arabic literary texts were slowly replaced with selections from works such as Alf Layla wa-layla (A Thousand and One Nights), the twelfth-century works of Al-Mufassal of Zamakhshari, Ibn Tufayl’s novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, and the Diwan of Hassan b. Thabit, a companion of the Prophet. Poetic texts ranged from the pre-Islamic work of Zuhayr b. Abi Sulma to the 13th century Burda of al-Busiri. Honours students could look forward to the 14th century Muqaddima of Ibn Khaldun.

This menu of texts began to change during the 1920s. The foundational writings of the Quran and the Hadith collection Sahih of al-Bukhari, along with the commentaries of al-Baidawi, remained central (although in time they would be replaced by the works of Richard Bell and Montgomery Watt in the field of Quranic studies) but the Arabic literary texts were slowly replaced with selections from works such as Alf Layla wa-layla (A Thousand and One Nights), the twelfth-century works of Al-Mufassal of Zamakhshari, Ibn Tufayl’s novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, and the Diwan of Hassan b. Thabit, a companion of the Prophet. Poetic texts ranged from the pre-Islamic work of Zuhayr b. Abi Sulma to the 13th century Burda of al-Busiri. Honours students could look forward to the 14th century Muqaddima of Ibn Khaldun.

This emphasis on the early Islamic period was also true of the set historical works. Al-Tabari’s Annals dating to the ninth century gave way but only to the even older Buldan of al-Baladhuri, the Abbasid historian of the great Arab expansion, and the Ummayyad section in the later 14th century al-Fakhri of Ibn al-Tiqtaqa. Only after 1945, did modern writers such as Egyptians Taha Husayn, ‘Abbas Mahmud al-‘Aqqad and Tawfiq al-Hakim begin to appear on the syllabus. Even so, the classical period continued to be the mainstay of the curriculum, a focus that the students themselves may have favoured. As Pierre Cachia noted, looking back on his career at Edinburgh, ‘I…[instituted] an optional course in modern Arabic literature, but during the first nineteen years there were only two takers.’

Spoken Arabic

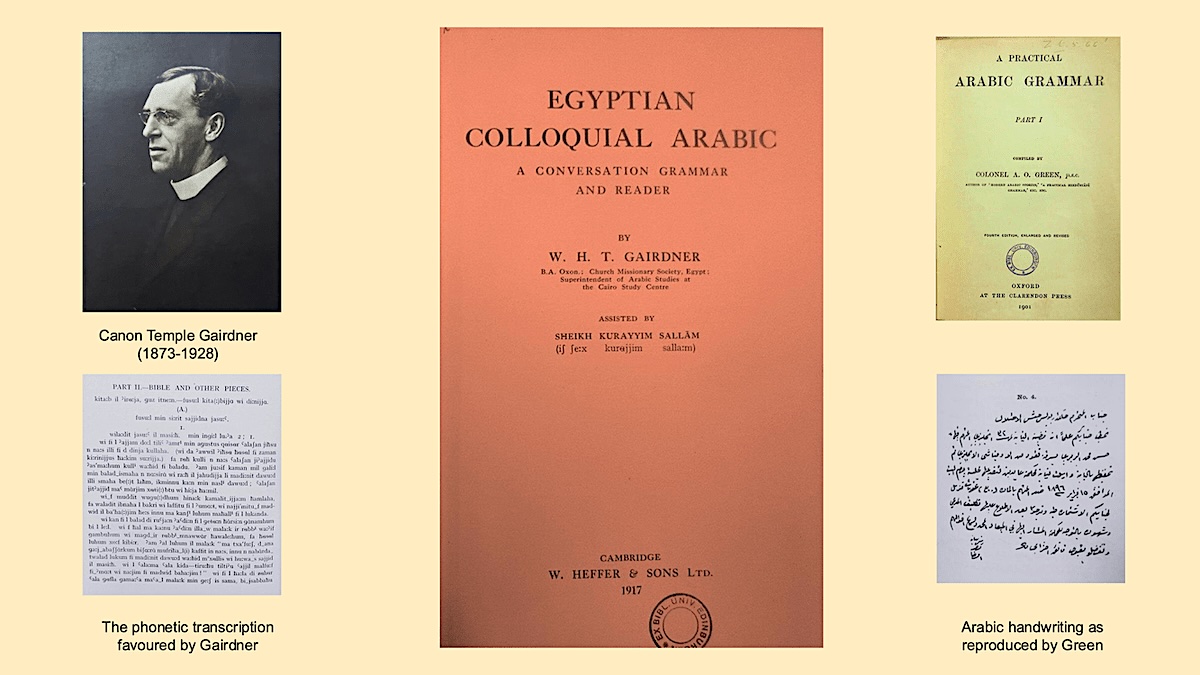

Despite the strong tradition of classical Arabic at Edinburgh, the teaching of spoken Arabic (al-‘ammiya) had been one of the designated tasks of the Arabic Lectureship when established, even if its teaching warranted a salary supplement. From 1920 it was taught for one out of the three hours each week in the Junior Class (although not for the senior classes), and was offered as well as a possible separate summer course. The teaching of spoken Arabic drew not on the pedagogical traditions of German philology but on the more practical arts of imperial administration and missionary endeavour. Initially Colonel A.O. Green’s A Practical Arabic Grammar, a text originally composed in the 1880s to assist British officers in occupied Egypt, served as the course book offering basic grammatical analysis illustrated by printed and handwritten Arabic texts (below right). In the early 1930s this gave way to Egyptian Colloquial Arabic, a work by Rev. Temple Gairdner, a Scottish-born missionary based for many years in Cairo, and composed with an Egyptian, Sheikh Kurayyim Sallam. This text heavily reflected its missionary inspiration with various Biblical passages and stories from the life of Jesus, rendered in an unfamiliar phonetic alphabet (bottom left). Spoken Arabic remained a secondary priority, although the encouragement from 1951 to spend six months in an Arabic-speaking country at the end of 2nd year, provided an opportunity for the committed student to work on verbal fluency.

Persian and Turkish

As newer additions to the university curriculum, the teaching of Persian and Turkish contrasted with the heavy classical emphasis of Arabic and its German pedagogical influence. In the early 1950s the elementary class used the Persian Grammar of Ann Lambton and a range of Persian schoolbooks, while at a more senior level, literary texts included the Golestan of Saadi and selections from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, as well as a number of poetic works. An Honours unit was dedicated to Persian dialects. For general reading on Iran, the established works of Percy Sykes’ History of Persia (first pub. 1915) and EG Browne’s Literary History of Persia (1902) were recommended as well as the more recently published Modern Iran (1942) of Elwell-Sutton. By the 1960s, Persian students were being encouraged to spend the long vacation at the end of their third year in Iran.

No formal tradition of teaching Turkish at Edinburgh existed until an elementary level course was launched in 1950 with a full programme to Honours level established soon after, which included the use of the Arabic and ‘Roman’ alphabets, and so access to Ottoman and modern Turkish. The Ottoman grammar of Jean Deny served as the basic reference with the reading collections of Paul Wittek and S. Topalian, the short stories of Reșat Nuri Güntekin and Hikmet Feridun, and the work of Ahmet Refik (the last in Arabic alphabet) providing further reading material. At Honours level prescribed readings included the work of Halide Edip, Ahmet Cevdet’s Tarih [History] and Ismail Habib Sevük’s anthology of post-Tanzimat literature.

Islamic History

Before the Second World War, the history of the Middle East had been taught as part of the Arabic language course. In 1951 Islamic History was established as a separate course open to all students and without any language requirement in 1951. Part of the opening up of the curriculum, the course covered the period from time of the Prophet Muhammad right up until the 20th-century across the full year. From a long list, it recommended the Arab histories of Philip Hitti and Bernard Lewis for the early Islamic period, the works of Gibb on Islam, of George Antonius, Albert Hourani and Stephen Longrigg on the modern Arab world, and of William Haas on Iran.