Students were drawn to the study of the languages, history and culture of the Middle East at Edinburgh for different reasons. One of the earliest known examples, James Anderson, studied Arabic and Persian under James Robertson in the 1760s before embarking on an administrative career in India. The three Hebrew students, John Barbour, George Purves and James Johnstone, who first took Arabic as a formal course with David Liston in 1859, were probably focused on more religious interests. In time students could engage with the Middle East in different ways: in pursuit of a degree in Semitic Languages, focusing on a comparative philology of Biblical Hebrew and early Islamic texts, or under the rubric of Modern Oriental Languages, where Arabic could be taken with Persian, Turkish or Spanish. Later, those without the necessary skills or interest in languages could do Islamic History as part of a History degree.

During the interwar period students taking Arabic began the week with a Monday afternoon lecture on Arab history and literature in the Old College. Arabic language was taught on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays at 2pm at junior level and 3pm for senior classes, that is four 4 hours a week across about 25 weeks of teaching. At a certain point this was increased to three levels of Arabic (Elementary, Ordinary and Honours). The small Arabic classes attracted both male and female students, bearing both familiar British names but also some Muslim names as well.

The PhD degree would also become a significant option for study of the Middle East. Created as a new degree programme after World War I, this attracted few students in the field of the Middle East and Islamic Studies during the interwar period, and these chiefly religious studies scholars from the English-speaking world. However, after 1945 increasing numbers of foreign students, including those from the Middle East, were drawn to study Islam under the supervision of Montgomery Watt who was establishing himself as one of its preeminent scholars working on islam in the West.

Some Edinburgh graduates went on to distinguish themselves in the field of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies. Others, perhaps less well-known, applied their specialist knowledge in different roles as linguists, administrators, soldiers, missionaries and writers. Taken together they embodied the long tradition of the study of the Middle East at Edinburgh.

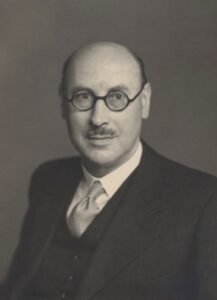

Sir Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb (often styled HAR Gibb) (1895-1971) was arguably the preeminent Orientalist scholar of his generation. Born in Alexandria, Egypt, Gibb was sent to the Royal High School, Edinburgh, at the age of five and began his university studies at Edinburgh in the new Semitic Languages programme in 1912. His degree was interrupted by the war while Gibb served in the Royal Field Artillery in France and Italy but he returned to Edinburgh in 1919 to receive a ‘war privilege’ MA. In 1922 an MA in Arabic at the School of Oriental Studies, London, followed where Gibb taught Arabic subsequently until 1937 when he was appointed to the Laudian Arabic Chair at Oxford. He moved to Harvard University in 1955 to become Professor of Arabic and Director of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies where he played a leading role in teaching, research and administration. He published extensively, including the multi-volume Islamic Society and the West (with Harold Bowen), described by Andre Raymond as ‘the last great work of European orientalism’. Among many honours was an honorary doctorate from Edinburgh and a knighthood (1954).

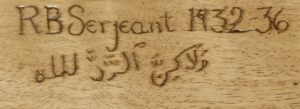

Robert Bertram Serjeant (1915-1993) graduated with an MA in Semitic Languages at Edinburgh in 1936, then a PhD at Cambridge in 1939. He returned to Edinburgh in that year to take up a Tweedie Fellowship when he catalogued the Oriental manuscripts in New College Library, later published as A Handlist of the Arabic, Persian and Hindustani MSS of New College, Edinburgh (1942). After a period of research on South Arabia at SOAS, Serjeant saw war service in Aden, then returned to England to teach at SOAS and to secondment in the BBC’s Eastern Service. Appointed Reader, then Professor of Arabic at SOAS, Serjeant moved to Cambridge in 1964, eventually retiring as the Thomas Adams’ Professor of Arabic in 1982. A prolific author and editor of publications on a wide range of Middle Eastern subjects, especially relating to Yemen and South Arabia, he was also known for his strong spoken Arabic, something no doubt reinforced by his years of fieldwork. He left his personal library to the University of Edinburgh, now catalogued in the Main Library, and his name carved in the desk of the Islamic Library (below).

After being rejected for military service, Australian-born Arthur Jeffrey (1892-1959) taught at the Madras Christian College in India during the First World War. He returned to Australia where he graduated with a BA (1918) and MA (1920) from the University of Melbourne before accepting a post at the School of Oriental Studies, American University in Cairo, in 1921. In 1929 Jeffrey completed his PhD, titled ‘The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur’an’ in the Department of Theology at Edinburgh under the supervision of Richard Bell. Jeffrey’s interest in textual criticism of the Qur’an and his virtuosity as a linguist were a feature of his dissertation, which traced the origin of some 300 non-Arabic words in the Qur’an, as well as of his later work. One of his examiners (Richard Bell) noted, ‘His linguistic equipment is adequate and indeed remarkable. His index shows lists of words quoted from 34 languages and dialects.’ The dissertation, subsequently published as a monograph, The Foreign Vocabulary of the Quran (1938), became a classic in the field. (It has been republished more recently by Brill in 2007.) In 1938 the University awarded Jeffrey a D.Litt. and he left Cairo to take up the post of Professor of Semitic Languages at Columbia University, becoming the first chair of the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Languages in 1954. A Methodist minister, he also taught at the Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He died in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1959.

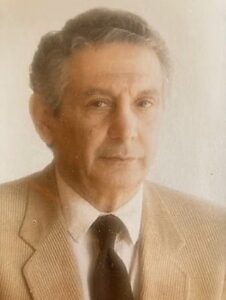

A Lebanese scholar and specialist in Islamic philosophy, Majid Fakhry (1923–2021) received his PhD from the University of Edinburgh in 1949, with a dissertation titled ‘Causality in Al-Ghazali, Averroes and Aquinas’. After graduating he held a series of academic positions at several institutions, including the American University of Beirut, where he served as chair of the Philosophy Department, SOAS, UCLA, Princeton University, and Georgetown University. During his career, Fakhry authored numerous books, articles, and manuscripts, contributing significantly to both Arabic and English language scholarship, and employing a historical and philological approach with a particular interest in the connections between ancient and Arabic/Islamic philosophy. His works include more than 15 titles in Arabic, with the most recent being Dirasat Jadida fil Fikr el ‘Arabi (2007). His History of Islamic Philosophy, published in 1970 is widely regarded as the first comprehensive historical overview of Islamic thought and has been influential in the study of Islamic intellectual traditions.

Abdin Mahmud Dajani (1921- ?) was born in 1921 in Jerusalem, the son of Sheikh Mahmud Dajani. After obtaining a BA from Beirut, Dajani came to Britain and qualified as a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn in 1947. The following year he moved to Edinburgh, a move said to have been encouraged by his relative, Subhi Dajani, and began his doctoral studies under the supervision of Montgomery Watt, ultimately graduating with his doctoral thesis ‘The polemics of the Qur’an against Jews and Christians’ (Theology), in 1953. While still a student Dajani was appointed as a Tutorial Assistant to help in the teaching of colloquial Arabic in 1950 and so became the first native speaker of the language to do so. Following his graduation, Dajani worked for a time for the United States Information Services in Amman and then for the Jordanian Ministry of Education where he became Chair of Cultural Relations. The interest in interfaith relations demonstrated in Dajani’s doctoral dissertation was also evident in his involvement in Muslim-Christian conferences held in Egypt during the 1950s.

Scholar, author and editor, Sylvia Gourgi Kedourie (née Haim) (1925-2016) was born in Baghdad in 1925 where she attended the Alliance Israélite Universelle Girls’ School. In 1947 she travelled to Britain with family and subsequently enrolled for a PhD at the University of Edinburgh. In 1953 she completed her doctoral thesis on the work of Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi, the Syrian writer who in the late-19th century advocated an Arabian caliphate and later came to be seen as a precursor of pan-Arab nationalism. Among her published work, she is perhaps best known for her Arab Nationalism: An Anthology (1962), but she also produced a number of studies on Turkey. Sylvia Kedourie is often associated with her husband, Elie Kedourie (1926-1992), whom she married in 1949 and with whom she produced a number of books. In 1992 she succeeded him as editor of Middle Eastern Studies, a journal that he had set up in 1964 and which has become a leading publication on Middle Eastern history and politics. She continued to edit this until her own death in 2016.