From its earliest beginnings the languages and culture of the Middle East at the University of Edinburgh were taught overwhelmingly by churchmen. Predominantly Scottish-born and of modest social circumstances, these scholars received their religious training and education locally in theology and languages before pursuing further study abroad, more often in Europe than England. Some carried out missionary work before taking up their posts at Edinburgh, which most often was their last career position.

The first teacher of Arabic, Rev. James Robertson, was born in Cromarty and studied at the Theological College, Edinburgh before taking a post at the nonconformist Northampton Academy. In 1749 he travelled to Leiden to study ‘eastern languages’ under the Dutch orientalist Albert Schultens, and then under his son, Jan Jacob. Armed with a letter of recommendation from Thomas Hunt, Professor of Arabic at Oxford, Robertson was appointed to the Hebrew Chair at Edinburgh in 1751. This made him, according to a later University Principal, Sir Alexander Grant, ‘the first really qualified professor who held the Chair.’ (Grant, History II, 292). Over a long career Robertson published work on both Hebrew and Arabic as well as carrying out the duties of University Librarian.

The extent to which Arabic was taught after Robertson is unclear although William Moodie (Chair 1793-1812) is known to have taught both Arabic and Persian on an informal basis. Not until the long tenure of Rev. David Liston (Chair 1847-1880) did Arabic become a formal subject at Edinburgh. A former student of Hebrew at the University, Liston had pursued missionary work in India after his graduation before returning to Britain in 1847 to take up the Chair at Edinburgh. Initially concentrating on Hebrew while also offering Syriac and Hindustani to the senior Hebrew class, in 1859 Liston decided to offer Arabic to senior students, something partly motivated by a wish to supplement his modest professorial income. This marked an important stage in the development of the language. The practice was maintained by his successor, David Laird Adams (1880-1892), with Arabic alternating with Syriac in his early years. Since then, Arabic has been taught with little interruption at the University, in time becoming a degree subject in its own right and involving not just the study of the language but also serving as an important reference point for the broader study of Middle Eastern history and culture.

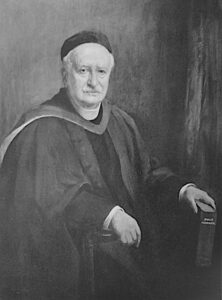

Born in the small fishing village of Whitehills, Banffshire (now Aberdeenshire), Rev. Archibald Robert Stirling Kennedy (1859–1938) presided over the development of Arabic as an independent subject. An Arts graduate from Aberdeen University (grad. 1879), Kennedy spent time at the Theological Hall at Glasgow University before continuing his studies at the Universities of Göttingen and Berlin. Returning first to Glasgow to take up a Fellowship in 1885, he accepted the professorial purple at the University of Aberdeen in 1887. Following the death of John Dobie, whose short-lived tenure had ended prematurely in a train accident, Kennedy became Professor of Hebrew and Semitic languages at Edinburgh in 1895. He would hold the post for more than forty years. Kennedy’s teaching focused on Hebrew but he taught Arabic with junior assistants in his early years of his appointment. Despite his support for the expansion of Arabic at the University, his own scholarship revolved around philological and scriptural subjects. He edited a series of grammars translated from the original German, of Hebrew, Syriac, Assyrian and Arabic, and wrote commentaries on books of the Old Testament; he also had an interest in archaeology as well as the economic and social life of ancient Palestine. Although never affiliated with a parish he was actively in the movement to convert Jews to Christianity.

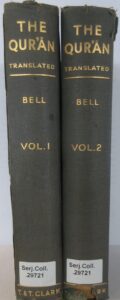

The appointment of Rev. Richard Bell (1876-1952) as the first Lecturer in Arabic at Edinburgh in 1912 marked a new phase in the teaching of the Middle East. Of Dumfriesian origin, Bell took a degree in Divinity and Semitic Studies at the University of Edinburgh in 1904, during which time he served as an assistant to Kennedy. On graduation he was licensed as a minister in the Church of Scotland and ordained to the parish of Wamphray in 1907. After only a year Bell resigned the Arabic lectureship for unknown reasons in 1913 and was replaced by Edward Robertson but he returned in 1921 to resume the position. Over the next 25 years he would be responsible for Arabic pedagogy at Edinburgh and establish his reputation as an eminent scholar of the Quran, based principally on his translation and a radical thesis that sought to challenge the traditional order of the suras. In 1921-24 Bell delivered the Gunning Lectures, subsequently published as The Origin of Islam in its Christian Environment (1925), and was awarded a Doctor of Divinity at Edinburgh in 1928. His translation of the Quran was published in 1937-39 as The Qur’an, Translated with a Critical Rearrangement of the Surahs. He retired as Reader in 1947, and died in 1952 before seeing the proofs of his life’s work, Introduction to the Koran, which appeared the following year.

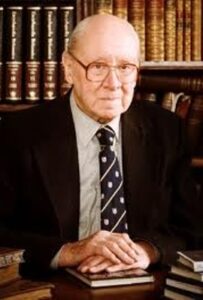

The foundation stone for Arabic and Quranic studies laid by Bell would be expanded by his successor William Montgomery Watt (1909-2007). Born the son of a Church of Scotland minister in the small village of Ceres in Fife, Watt first took a Classics degree at the University of Edinburgh in 1929. He followed up with another undergraduate degree in philosophy and ancient history at Oxford before returning to Edinburgh for an unsuccessful PhD attempt. His interests were chaning and by the time of his ordination as a priest in the Episcopalian Church in 1939, Watt had already begun to take a particular interest in Islam. This led him to reenrol as a doctoral student and complete his PhD titled ‘Predestination and Free Will in Islam’, under the direction of Richard Bell in 1943. The following year Watt accepted the position of Chaplain to the Anglican bishop in Jerusalem but the difficult political situation made life there uncomfortable. He returned to Edinburgh in 1947 where he soon took up the position of Lecturer in Arabic vacated by Richard Bell. Over the next thirty years and more Watt established an international reputation as a scholar of Islam, retiring as Professor of Islamic Studies in 1979, when he was replaced by Carole Hillenbrand, the first female appointee in the Department. Among a large number of publications, Watt’s works on the Prophet Muhammad stand out as particularly significant contributions to the field and important examples of an approach that sought to counter the negative images of Islam and Muhammad prevalent in Europe and the West and to represent a more ecumenical view.

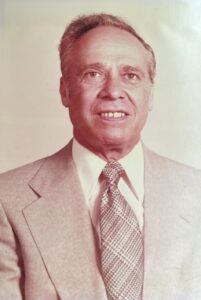

The long succession of Scottish churchmen teaching Arabic at Edinburgh ended with the appointment of Pierre Cachia, Egypt born of Maltese and Russian parents. An American University in Cairo graduate, Cachia had served in the British Army during the war where he made some Scottish connections. After two years’ of teaching at AUC, he began his PhD at Edinburgh under the supervision of Watt, which he completed in 1951 by which time he was already employed as an Arabic lecturer in the department. This different personal trajectory expressed itself in his varied academic interests which, unlike that of his predecessors, were focused on different genres of modern Arabic literature. His first book, based on his PhD, discussed the work of Egyptian writer, Taha Husayn; among others, his An Overview of Modern Arabic Literature (1990) stands out as a major contribution. He also co-authored A History of Islamic Spain (1965) with Watt. Cachia left Edinburgh for Columbia University in 1975 where he consolidated his international reputation as a scholar of modern Arabic literature and Egyptian folklore. The subsequent appointment of Sudanese ‘Abd al-Rahim ‘Ali to teach Arabic continued the trend away from doctors of the church.

In contrast to the long clerical tradition of Arabic pedagogy Persian and Turkish attracted scholars from quite different academic trajectories at Edinburgh. Persian had been taught intermittently at Edinburgh since the 1760s but it was not until the late 1940s that it became a formal subject with a Persian Department established soon after. Initially taught by A. Barclay Milne, Laurence Elwell-Sutton would occupy the post of Persian Lecturer from 1952 for the next three decades. Born in the village of Ballylickey, Co. Cork, Ireland, and the son of a British naval officer, Elwell-Sutton was educated at Winchester College, then went on to study Arabic at the School of Oriental Studies in London where he graduated in 1934. His immediate subsequent career suggests an interest in business, politics and government more than anything academic. He worked for some years for Anglo-Persian Oil in Abadan, then returned to Britain where he was attached to the Ministry of Information as well as the BBC during the war. Between 1943-47, he served as press attaché at the British mission in Tehran. Such a career path may explain his wide range of interests in Persian language, literature, history and politics, all of which are evident in his long list of publications. In later years he regularly spent time visiting Iran. He retired as the inaugural Head of IMES in 1982.

John R. Walsh BA (1919-93) was the first Turkish Lecturer appointed at the University of Edinburgh. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Walsh served in the US Army in Europe during World War II where he received his first experience of oriental studies courtesy of a short course at SOAS in 1945. After his army discharge he returned to SOAS the following year to study Arabic, Persian and Turkish, ultimately graduating with a BA with first class honours in Turkish in 1950. He was appointed at Edinburgh the same year. Over the next thirty years he developed a reputation as an Ottoman literary specialist before his retirement in 1980.

In addition to this core of Middle Eastern and Islamic expertise, others at Edinburgh contributed to teaching especially after Islamic History, a grand survey course covering the history of the region from the classical to the modern period, became a formal subject in the early 1950s. These included the ideologically diverse talents of George Shepperson, an imperial African specialist, and Marxist Victor Kiernan, both of the History Department. In 1969 the arrival of Michael V. McDonald, a scholar of Middle Eastern literatures, and later Ian Howard (1939-2013), a Shi’ism specialist, added to the breadth of the expertise in the Arabic Department.