Introduction

For more than 250 years the University of Edinburgh has engaged in the teaching of the languages, histories and cultures of the Middle East, an area here defined as the Arab world, and the states of Turkey, Israel-Palestine and Iran. Now a diverse field of area studies, the study of the Middle East at Edinburgh first emerged from within the narrower confines of the Faculty of Theology during the latter half of the 18th century where philological and religious interests saw the teaching of Arabic to students of Hebrew. Yet, almost from the beginning the study of the Middle East has also been connected with the more worldly concerns of commercial life and imperial enterprise. Indeed, it has served as an arena where the intellectual, political, cultural and religious imaginings of the institution were articulated, configured and repurposed in a way that was consistent with its imperial mission of exploration, domination and administration. Not only an object of study, from the middle of the 19th century the Middle East became a region from which the University attracted increasing numbers of students who came to study a range of academic disciplines and degrees. This online exhibition examines the development of the Middle East as a field of study from its beginnings until the establishment of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies in 1980 while also recognising the intellectual, political and associational role played by students from the Middle East at the University.

Arabic Beginnings

The teaching of Arabic began at the University of Edinburgh in the late 1760s, when Rev. James Robertson, then the holder of the Hebrew Chair that had been established in 1642, first offered additional classes in the language to students studying Hebrew in the Faculty of Theology (later Divinity). The decision recognised the affinity of Arabic with Hebrew as a Semitic language as well as its central importance in the study of Islam, and its value in comparative religious studies. From that time Arabic (and to a lesser extent Persian) was taught on an irregular basis until 1859 when it became formally recognised as a subject for those in the Advanced Hebrew class. of the Faculty of Theology. The institutional matrix from which the study of Arabic, and by extension the study of Islam, emerged at Edinburgh that was anchored in a comparative religious studies framework would exert a powerful influence on the development of its pedagogy.

The Call of Empire

Interest in the Middle East was not only generated by linguistic and theological concerns but by a strong commercial and imperial rationale. This was already evident during the 18th century when commercial agents, such as the East India Company, offered promising careers to those with relevant linguistic skills and administrative abilities. In Scotland, Henry Dundas (1742-1811), Viscount Melville, used his network of personal connections to promote the cause of aspiring Scottish applicants. The establishment of the Indian Civil Service Exam in 1855 offered a more formalised career route, with universities such as Edinburgh well placed to offer a the necessary language training to those seeking to secure such employment.

Principal, University of Edinburgh (1885-1903)

At Edinburgh this combination of academic learning, imperial service and commitment to education was most clearly embodied in the figure of Sir William Muir (1819-1905), who was appointed Principal of the University of Edinburgh in 1885. A native of Glasgow and veteran of almost 40 years of government service in India, Muir was also a gifted linguist and scholar of Islam, whose work was dedicated to demonstrating the superiority of the Christian faith. He, along with his older brother, John Muir (1810-1882), a former East India Company officer and Sanskritist, and who would endow a Sanskrit Chair at Edinburgh, would serve as models of the scholar-imperialist. However, as Avril Powell notes, this represented a decidedly mixed legacy,

…William Muir presents the paradox of a scholar drawn irresistibly to the Arabic literary heritage and to

close friendships with individual Muslims, who nevertheless felt compelled by his religious convictions

to denigrate Muslim beliefs and social institutions in both their Arabian and Indian settings.

Up to this period India had dominated British imperial priorities in the East but these were now expanding to western Asia. Greater British involvement in the Gulf, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the occupation of Egypt in 1882, gave the Arabic-speaking world and the Middle East greater geopolitical relevance. The defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I and its subsequent dismemberment brought Britain even greater influence in the region. The League of Nations mandates of Iraq and Palestine, the latter which incorporated the 1917 declaration named after the British Foreign Secretary and Chancellor of the University of Edinburgh, Arthur Balfour, signalled a firm British commitment to the region.

Already in 1897, in a graduation address titled ‘A Plea for the Encouragement of Oriental Studies’, Archibald Kennedy, Professor of Hebrew and Semitic Languages, had joined a growing national chorus calling for British institutions of higher learning to train people for the administration of the needs of the Empire and its diverse peoples. At Edinburgh he called specifically for the establishment of an Arabic lectureship to deal with this need. For the time being Arabic continued to be delivered by the Hebrew Chair with support from an assistant. Only in 1911 did the University accede to Kennedy’s call and agree to establish a post with duties including the teaching of classical Arabic, Arabic Literature and Comparative Semitic Grammar. Despite some initial disruption during World War I, Arabic was now put on a firm footing.

During the interwar period, the study of the Middle East was closely tied to the study of Arabic with a strong focus on the early centuries of Islam as foundational to an understanding of the region. The language could be taken as part of a Semitic Languages degree or in a Modern Oriental Languages programme. The study of the literature, culture and above all religion of the Middle East was framed around a close reading of original texts. The study of its history for the non-specialist, from classical to modern times, and styled as Islamic History, would come later.

Postwar Trajectories

In 1947 the study of the Middle East received new impetus with the Scarborough Report which proposed an expanded national vision for Middle Eastern (and other) languages in British universities in the emerging postwar world. By 1952, Edinburgh could boast an expanded Arabic department as well as separate Persian and Turkish departments, with active Sanskrit and Urdu sections. All housed together at 6 Buccleuch Place, a configuration that suggested an emerging area studies’ conception, the building was named the William Muir Institute after the man who represented the dynamic engagement of imperial administration, comparative religious scholarship and the study of Arabic.

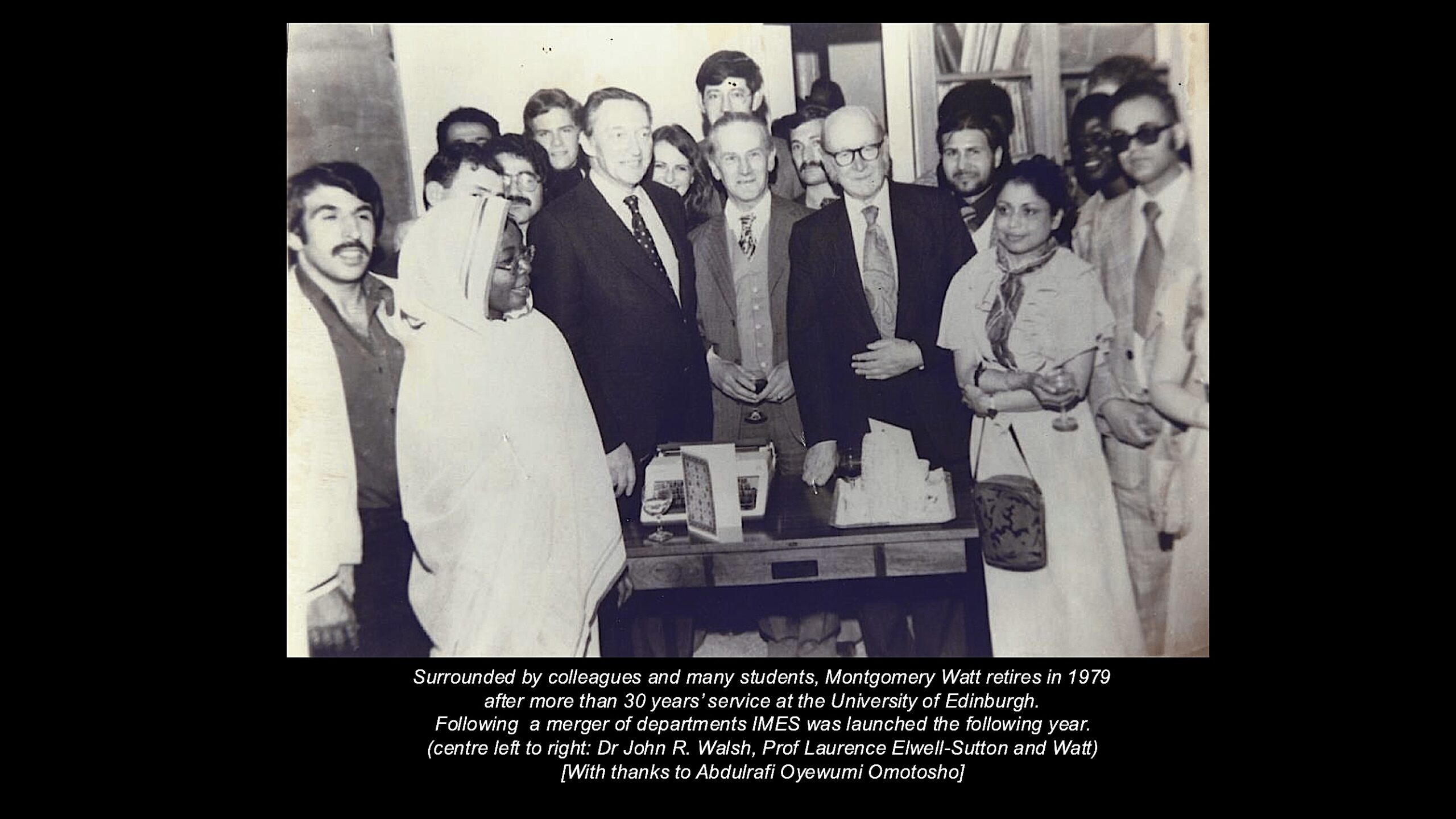

Over the next decades, the University of Edinburgh consolidated its reputation as an internationally recognised centre for the study of Islam and of the Middle East. This was due in no small measure to Montgomery Watt whose international status and sympathetic interpretation of Islam attracted students from around the world, and not least the Middle East. Watt remained the dominant figure in Arabic and Islamic Studies at Edinburgh until the end of the 1970s when he retired. His intellectual legacy was said to be one of the reasons why the University of Baghdad donated the sum of £250,000 in 1979 to endow the new Iraq Chair of Arabic and Islamic Studies that would help secure the future of the field at the University. In 1980 the Departments of Arabic and Islamic Studies, Persian and Turkish were merged to form Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies (IMES) which remains the centre of much teaching and research on the Middle East at the University today.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Nada Abo Arisha, Neelam Bharat Raval, and the staff of the University of Edinburgh Archives for their help in collecting the materials and in putting this online exhibition together; also to Henry Dee who provided material from an earlier study. Anja Pogačnik from the LLC Research Office offered valuable advice and encouragement. I would also like to thank the Moray Endowment Fund for its financial support.

Anthony Gorman (Anthony.Gorman@ed.ac.uk)