Week 3-Using Edinburgh as a mirror, we examine the invisible boundaries of public spaces.

This week’s course, through further study of exhibition ethics and the inspiring personal insights of Talbot Rice gallery’s curator, James, on exhibition curation, has led me to have a deeper reflection on my exhibition project. I intend to clarify my third-week exhibition thinking by answering the five questions posed by James in class.

Princes Street, Edinburgh, 2025

- Why exhibit? After reflecting on the exhibition form I conceived last week, I chose the structural imbalance of equality rights in public spaces in Edinburgh as the exhibition theme. This is not an abstract discussion but a reality confirmed by official policies. The new policy of the city council to increase tourist taxes starting from July 2026 has acknowledged the burden on public spaces caused by tourism growth. The implicit transfer of space usage rights during the Edinburgh Arts Festival also made the invisible boundaries of public spaces real. Inspired by the concept of “rejecting political silence” discussed in class, I hope to use art as a medium to awaken public reflection on the ownership of public space. This is a discussion without a standard answer.

- What makes the exhibition interesting? I set the exhibition route map as an autonomous check-in form, marking a point for each location visited. The interpretation rights are returned to the audience. And using the Edinburgh public transportation network as a connection form, a daily pass for public transportation can cover the entire route, which is both suitable for the relatively complete accessibility of the public transportation system in the local area and makes the exhibition an immersive experience. Taking a ride on the bus itself is also a way to perceive the power of public space.

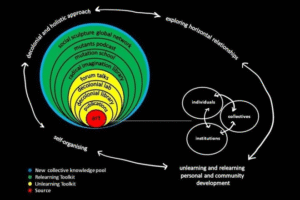

- Related to which main issues? As Edinburgh is a local manifestation of the universal problem of “global public space equity”, its predicament is not an isolated case but a common contradiction of tourist cities worldwide. I hope to use Edinburgh as an entry point to explore the question of “for whom should public space serve”, rather than limiting the complaint to a single city.

- Who is the target audience? The core target audience I set is local residents who have experienced the changes in space rights. They are the most sensitive to the changes in space rights. Next is foreign tourists, who can discover the neglected boundaries from a stranger’s perspective. At the same time, students, researchers, and the disabled community who are concerned about social justice are also welcome.

- The set criteria and moral red lines? The moral line I set for myself is not to extend to sensitive political issues, not to spectacleize any group, and to reject ethical compromise. In terms of criteria, all exhibition points are adapted to public transportation and accessibility needs; the logic of choosing public exhibition points and the sources of evidence; equal presentation of all audience feedback, and rejection of value judgment. This is also the thinking I gained from the discussion on “dynamic balance of power and inclusiveness” in this week’s class.