Educational Intervention in Visualizing Future Learning Organization.

As a non-native English speaker and an interdisciplinary student in Education Futures, I have observed that some international students, like me, experience challenges with classroom participation in their new major courses. The Future of Learning Organizations (FLO), as the first core course for new students in the Education Futures programme at the University of Edinburgh, establishes a foundational knowledge framework for students. In the classroom, native English speakers who have been studying a single discipline continually and the instructor are often able to quickly enter into a mode of rapid judgement and decision-making, whereas non-native international students who have no background in education futures majors hesitate to speak due to a lack of domain knowledge, speaking anxiety, and a listening load. This not only weakens their participation in the classroom and hinders their research in the field of education futures, but also inadvertently weakens their relationality with peers.

Therefore, this paper designs and (hypothetically) tests an interdisciplinary work-sharing co-creation activity in the last unit of the FLO, with the aim of opening up the participation of non-native English speaking students who are not confident in English and have insufficient professional knowledge, and also contributing to a higher level of collaborative rapport among the whole class in the future course.

This intervention is divided into two sessions:

The first session is the Anonymous Reflection and Relational Warm-up, which aims to ensure that students have a good understanding of FLO lectures before entering the Future learning visualisations activity, so that co-creation activities with their classmates go more smoothly. Therefore, in the first session, all students were invited to anonymously answer the following questions on Miro’s shared form: 1. Moments that felt stuck; 2. Clues that triggered your thinking; 3. Classroom conditions you would like to experience; 4. Future learning organization Visualization.

As Burbules (2000, p. 172) suggests, an aporia is a state of being ‘stuck, in-between’ as one moves into new areas or encounters new puzzles. However, the in-between of learning is not a sign of failure but rather a key to generating understanding, as it lies in the transition between the certainty of misunderstanding and the certainty of truth (Burbules, 2000; English, 2016). At the same time, Burbules (2000) proposes that aporia is categorised into three types, namely: knowledge vacuum, overwhelming choice, and choice visible but unable or unwilling to follow. Therefore, the second question is designed to help students recognise the reasons they are in a predicament, so they can get out of it more quickly. In addition, the last two questions were designed to guide the students to apply what they had learned in FLO to conceptualise learning organisations in the future in advance. Learning organisations are defined as organisations that continuously expand their capabilities through individual and collective learning to gain sustainable competitive advantage (Senge, 1990; Sreeja & Hemalatha, 2017). As Ross (2022, p. 11) emphasises, ‘there is no single present’, much less a single future. Therefore, future learning organisations may not be limited to a single physical space, such as a school, but may refer to any environment where educational activities can take place, potentially existing in communities, online platforms, or hybrid spaces. In particular, future classrooms can be seen as specific learning arenas within future learning organisations. Several scholars argue that technology has become inextricably linked to educational activities and environments, and that future classrooms are multiple spaces where digital, biological, and social aspects are intrinsically connected and co-determined (Fawns, 2019, p. 142; Forsler et al., 2025; Lamb et al., 2022). All of these concepts came from the FLO course, and placing them in the first session is intended to provide students with inspiration for their subsequent work.

The first session lasted about 15 minutes, and participants can then freely respond to their peers’ ideas and questions on Miro. This session aims to address doubts and confusion, enabling participants to communicate and collaborate more effectively during the co-creation activity and providing a buffer for students who are less confident in English, helping them better absorb the knowledge and prepare for the follow-up activity.

The second session is the Collaboration Workshop, which requires everyone to work together in small groups to create a blueprint of an ideal future learning organisation. Since everyone has a general knowledge of the FLO after the first session, the impact of interdisciplinary issues on communication among participants in this session is almost negligible. Based on native language differences, students are divided into groups of three, with each group containing both native and non-native English speakers. The members of each group assumed fixed role restrictions:

A: only speak, not listen;

B: only listen, not speak;

C: only draw, not listen.

Therefore, two people in each group are required to wear earmuffs. Within the framework of the restrictions, the participants can use their imagination and other means of expression to convey information to their peers. The activity lasts for 20 minutes, after which the restriction is lifted and students are free to use the creative materials provided in the classroom (e.g., coloured cards, ribbons, balloons, models, etc.) to further refine their results within 5 minutes.

This co-creation activity is inspired by Roy Ascott’s Groundcourse Games (Sloan, 2019) and Aldridge (2022). Initially, this activity adopts the principles of creating a framework of restrictions in Groundcourse Games (Sloan, 2019, pp. 176-207) and is based on the Behaviourist Approach (BA) to impose restrictions that trigger participants’ communication constraints (e.g., auditory constraints) in specific response behaviours. This ultimately forced the group to create the dynamic communication approach (Sloan, 2019) to visualise the abstract “future organisation”. In addition, Aldridge (2022, pp. 3-7) contends that artistic and educational spaces should prioritize creating space

for diversity in sensory experiences and modes of expression. Therefore, this event advocates the use of drawing and collage as equivalent forms of communication, transforming language into visual blueprints and making the future learning organisations more visible. It also supports the inclusion of body language in the creative communication of the class to provide a variety of ideas for communication. It is hoped that this will enable the class to share a system of inter-lingual discussion, while steadily increasing the sense of participation and being heard in the classroom for non-native speakers.

In the end, the groups will collaborate on a visual image of the future learning organisations, which can be accompanied by a brief textual annotation. All work will be documented by each group through photographs or video recordings and uploaded to Miro as a collection of the final outcomes of the course. At the end of the activity, students will provide feedback in the form of anonymous sticky notes with three questions: ‘Were your ideas adequately heard?’ ‘Did this event make a difference to you academically or in terms of relationality?’ and ‘What suggestions will you make if the event is redesigned?’ to assess the effectiveness of the activity and gather input for further improvement.

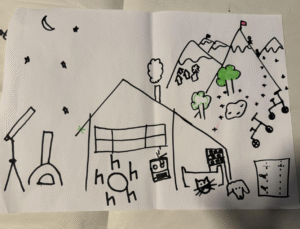

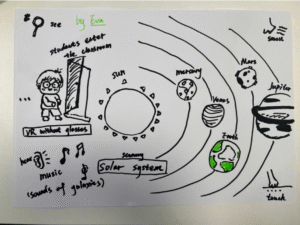

This is what my peers are doing in practice. It was interesting to see that we all had various wild ideas for the future learning organisations.

(Ailsa & Susu Wang & Jeffery Zhan & Ezra Gao, 2025)

(Eva Wu, 2025)

(Dorothy Kang & Mo Zhang & Soda Dai, 2025)

There are several shortcomings apparent in the design of this intervention.

Firstly, the participants in this intervention are limited as it is aimed at a group of new students in the Education Futures programme. This small sample size was primarily intended to reinforce the study’s pedagogical relevance. Learners from different colleges or cultures may face very different linguistic capital structures and classroom rhythms. Burbules (2002) notes that the efficacy of dialogue depends on the linguistic order and distribution of power in a specific context. Therefore, this targeted intervention may not be directly applicable to promoting relationality among international students from other programmes, their classmates, and teachers.

Secondly, in this intervention, all data are collected for one-time, anonymous, non-graded purposes, and numerical metrics (e.g., length of presentation, number of sticky notes, frequency of responses to peers) are not used to assess participation effects. As Selwyn and Gašević (2020) critique, the misuse of learning analytics tools in higher education tends to replace real learning experiences with computational proxies. The significance of the FLO for students is that it introduces them to the field of Education Futures, and the focus is on whether they have mastered the course. This is because grades do not fully reflect a student’s effort in understanding a subject. According to Davids (2015), the value of learning is not in measurable outcomes, but in meeting and generating uncertainty. Moreover, the results of the data measurements do not contribute quickly and directly to international students who are non-native English speakers and interdisciplinary in promoting their classroom engagement and relationality with their peers and teachers.

Thirdly, a reflection on creativity. Although the intervention is structured to introduce role constraints and multimodal expression, creativity remains confined to the classroom, and the intervention’s framework is primarily derived from the teacher’s classroom activities. This is an issue for reflection, which is why I try to modify the intervention design based on the suggestions participants submit at the end of the activity.

In conclusion, this study focuses on international students’ classroom engagement through a two-phase intervention that creates a more comfortable, low-threshold entry point for non-native speakers with low confidence in English to express themselves and brings their relationality with classmates closer. However, there is still room for further improvement in this intervention programme, including expanding the sample, balancing datamining, and deepening creativity. Future versions of the FLO intervention should continue to promote the redesign of international students’ relationality with their peers and teachers in a more open social and technological environment.

References

Aldridge, L. (2022). RBTL: Laura Aldridge. Artlink Edinburgh. https://www.artlinkedinburgh.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2022/01/RBTL_LAURA-ALDRIDGE.pd

Burbules, N. C. (2000). Aporias, Webs, and Passages: Doubt as an Opportunity to Learn. Curriculum Inquiry, 30(2), 171–187. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3202095

Burbules, N. C. (2002). The limits of dialogue as a critical pedagogy. In Revolutionary pedagogies (pp. 273-295). Routledge.

Davids, N. (2015). On the Un-becoming of Measurement in Education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(4), 422–433. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1068682

English, A. (2016). The ‘in-between’ of learning: (Re)valuing the process of learning. In P. Cunningham & R. Heilbronn (Eds.), Dewey in our Time: Learning from John Dewey for Transcultural Practice, pp. 128-143. UCL IoE Press.

Fawns, T. (2019). Postdigital education in design and practice. Postdigital Science and Education, 1(1), 132–145. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0021-8

Forsler, I., Bardone, E. & Forsman, M.(2025). The Future Postdigital Classroom. Postdigital Science and Education, 7, 682–689. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s42438-024-00488-y

Lamb, J., Carvalho, L., Gallagher, M., & Knox, J. (2022). The postdigital learning spaces of higher education. Postdigital Science and Education, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00279-9

Ross, J. (2022). Digital futures for learning: Speculative methods and pedagogies. New York: Routledge.

Selwyn, N., & Gašević, D. (2020). The datafication of higher education: Discussing the promises and problems. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 527–540. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1689388

Senge, P.M. (1990), The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Doubleday, New York, NY.

Sloan, K. (2019). Art, Cybernetics and Pedagogy in Post-War Britain: Roy Ascott’s Groundcourse (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.4324/9780429468018

Sreeja, K., & Hemalatha, K. G. (2017). A Review on models of Learning Organization. Asian Journal of Management, 8(1), 112-116. https://ajmjournal.com/HTML_Papers/Asian%20Journal%20of%20Management__PID__2016-8-1-18.html