Week 11 Blog|Audience Feedback, EDI and Ethics Reflection, and Project Timeline

This week, I further developed critical aspects of my Expanded Cinema project, focusing on audience feedback mechanisms, equality, diversity, inclusion (EDI) and ethics considerations, and a detailed production and public timeline.

Audience Feedback Mechanisms

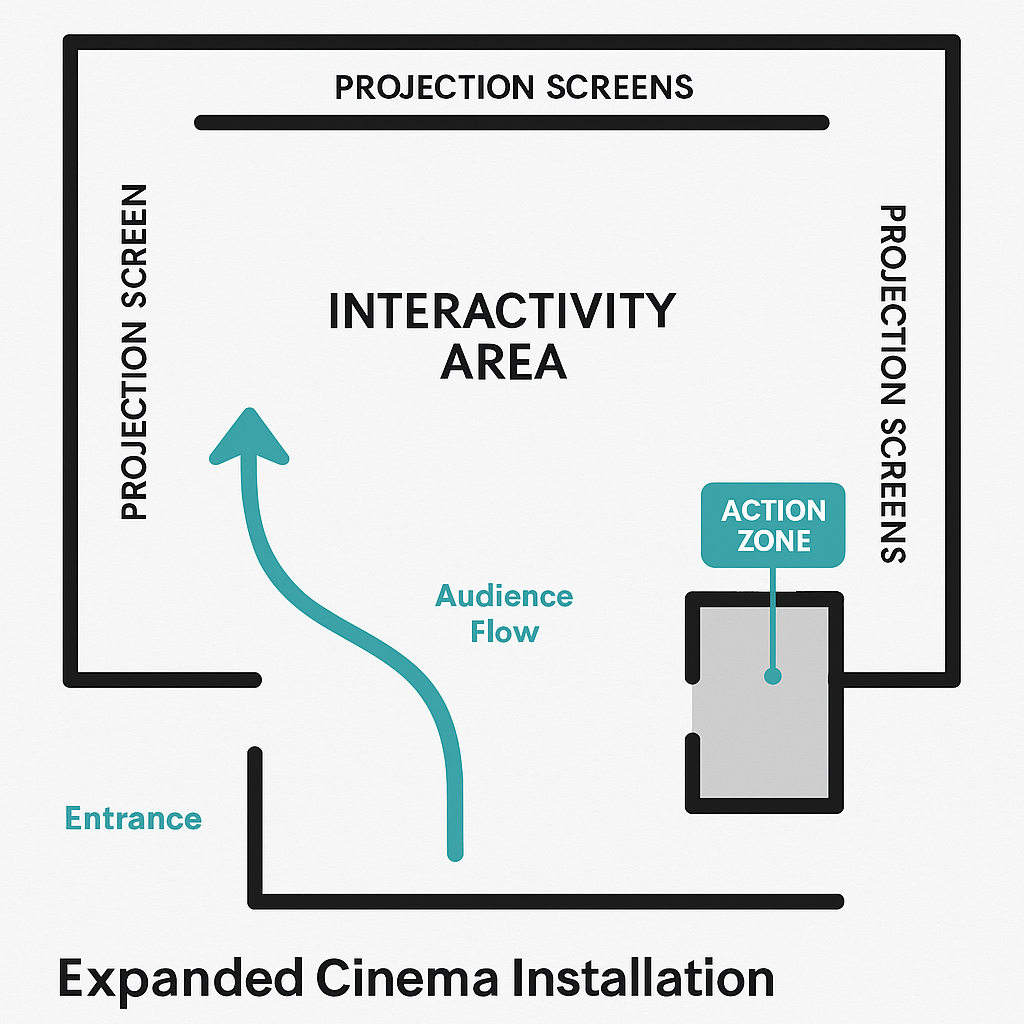

In The Living Screen exhibition, the audience moves beyond mere participation; they become co-creators of cinematic narratives. To support this agency, I designed the following feedback systems:

-

Individual Feedback|Movement Path Replay

After completing the experience, visitors can scan a QR code onsite to access a personal interface showcasing their movement paths (such as raising hands, turning, crouching) and the triggered cinematic responses. Each participant can view and download their personalized one-minute short film. This system invites visitors to reflect on how their physical gestures dynamically shaped narrative structures (Proposal, 2025). -

Community Feedback|Ongoing Narrative Community

An open online community (e.g., Discord, WeChat) will be established, inviting participants to share their generated short films, creative edits (GIFs, screenshots), and engage in dialogue on topics such as “How does narrative agency change your way of seeing?”. This strategy transforms the project from a one-off exhibition into a growing storytelling ecosystem (Proposal, 2025).

Through these strategies, the feedback system embodies the Expanded Cinema ethos where “behavior itself becomes language” (Youngblood, 1970), and extends the experience into a continuous narrative afterlife (Huhtamo, 2015).

EDI and Ethics Reflection

Informed by ECA’s EDI policy (ECA, 2023), the ethics lecture, and my personal ethics manifesto, the project actively integrates the following considerations:

-

Physical Diversity and Accessibility

All interactive gestures (raising hands, turning, crouching) are intentionally simple and adaptable for diverse physical abilities. Venue layouts guarantee wheelchair accessibility and unblocked pathways (Proposal, 2025). -

Cultural and Linguistic Inclusivity

All instructional materials combine plain English with universal pictograms to minimize linguistic barriers. Prompt cards use poetic, open-ended language to respect cultural differences and maintain openness (Proposal, 2025). -

Safeguarding Young and Vulnerable Audiences

Although the project does not specifically target minors, it adheres to safeguarding protocols based on Creating Safety: Child Protection in the Arts guidelines, including procedures for parental consent where needed (Children in Scotland, 2023). -

Respect for Copyright and Intellectual Property

All media used (video, sound) is either original, properly licensed, or used under educational fair use, with clear crediting. A contingency for licensing fees has been included in the project budget (Proposal, 2025).

The project adheres to a fundamental ethical framework emphasizing voluntary participation, anonymous interaction, and non-punitive engagement, ensuring that immersive interaction remains empowering and respectful (Ascott, 2003).

Project Timeline and Public Schedule

Aligned with production and budgetary planning, the following schedule has been developed (Proposal, 2025):

| Stage | Dates | Key Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Planning | 5–10 May 2025 | Finalize curatorial concept, confirm artists |

| Technical Preparation | 11–18 May 2025 | Equipment booking, testing, finalize content |

| Site Setup & Installation | 20–22 May 2025 | Installations of AV systems, calibration |

| Internal Testing | 23 May 2025 | Final health and safety checks |

| Public Exhibition | 24–30 May 2025 | Exhibition opening, workshops, artist talk, guided tours |

| De-installation | 30–31 May 2025 | Pack-down and venue restoration |

Public-Facing Schedule:

-

24 May, 14:00–18:00|Exhibition Opening and Curatorial Introduction

-

25 May, 13:00–15:00|Workshop: Body as Editor: Gesture and Nonlinear Narrative

-

26 May, 14:00–16:00|Artist Talk and Q&A Session

-

27–29 May, 11:00–13:00|Optional Guided Tours

-

30 May, 14:00–16:00|Closing and Audience Feedback Event

The timeline ensures a balance between setup, audience accessibility, public programming, and sufficient safety margins, fully compliant with University health and safety regulations (Proposal, 2025).

References (Harvard style)

-

Ascott, R. (2003) Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness. Berkeley: University of California Press.

-

Children in Scotland (2023) Creating Safety: Child Protection in the Arts. Available at: [https://childreninscotland.org.uk/creating-safety-child-protection-in-the-arts/] (Accessed: 28 April 2025).

-

Edinburgh College of Art (2023) Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Policy. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

-

Huhtamo, E. (2015) ‘Expanded Cinema’, in Elwes, C. (ed.) Installation and the Moving Image. New York: Columbia University Press, Chapter 9.

-

Proposal (2025) The Living Screen: An Expanded Cinema of Behaviour, Jiyun Zhang. Internal project document.

-

Youngblood, G. (1970) Expanded Cinema. New York: Dutton.